The post-PC, post-print revolution, and how it affects writers

Anyone who reads this blog, however occasionally, or knows me in real life, will be aware that I sit in the bizarre middle ground between “enthusiastic about new technology” and a semi-Luddite appreciation for the 19th century. I use modern technology every day, yet I study traditional signwriting and calligraphy; I read on a Kindle yet scour second hand bookshops for antique volumes. When in the mountains I enjoy climbing with old-fashioned equipment, but I am in awe of the achievements of today’s leading climbers, achieved thanks to their dedication not only to training, but to the latest technology.

Originally, my practical, hands-on interest in the 19th century was cultivated by a desire to really step into the boots of my characters and see the world how they would have seen it. Since then I have become fascinated by something else: contrast. The world of the 1840s is so utterly different to the world of 2012 that the juxtaposition of these two extremes can provide valuable insights (and yet, in some ways, the social and economic problems of 1848 startlingly mirror the current European crisis).

For example, in 1842 Charles Dickens visited America. He was at the peak of his early popularity, and widely regarded as the most influential author of the period. Typewriters had not yet been invented; steel dip-pens were the only tool available for writing. Every single one of his works of genius was written out in hand on paper using pen and ink. He could not possibly carry around an entire draft of work with him, let alone large amounts of notes and reference material; this means that, although he undoubtably made notes, a lot of his material must have been stored mentally. He wandered the streets of London by night and locked away a thousand observations in his memory, ready for instant retrieval. His books resonate with detail and insight despite this primitive system of writing.

Dickens did not have access to the almost limitless powers that the digital cloud and mobile computing offer to the modern writer, and yet I am all too aware that his powers of memory and recollection will eclipse those of any author living today–simply because we do not use our mental faculties to their full potential. Dickens had no other choice.

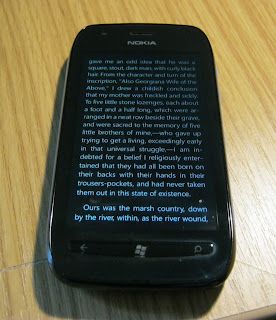

Consider my own writing system. I have a desktop-bound computer at home with a big screen and a full keyboard. This only ever gets used for long writing sessions or for editing and composing. I also have an old Palm portable computer, with folding keyboard; this is used for writing plain text anywhere else, and synchronises with my Dropbox folder (this is a form of storage cloud I use for all my documents). I also have a Nokia smartphone which connects to Dropbox, and a Kindle reader for storing more lengthy reference documents.

The key to this entire system is Dropbox, the centralised storage cloud that contains literally everything I might need. I can edit a file on my computer and the changes will transfer instantly to my phone (and also to my Palm as soon as it is synchronised). I can beam a document from my computer to my Kindle in a matter of seconds, and even if every single one of these devices were to be lost or destroyed, none of the data is affected in the slightest.

All this isn’t even considering the internet as a research tool–arguably even more significant to the modern writer than cloud storage. Relatively inexpensive pocket computers now exist–smartphones–that allow the writer to access the web from anywhere, at any time. You don’t need to spend hundreds or sign your soul away to the phone networks these days, either: anyone can afford a basic smartphone, and this puts the mobile web into anyone’s hands.

I sometimes wonder if these miraculous digital powers have made us lazy or complacent. I know that, if I need to know what occupation my main character’s father had, I can look it up in seconds from any corner of the planet–I don’t have to remember it, and I don’t even have to be at home in front of my computer. The upshot of this is that, as nothing has to be remembered, very little actually is remembered–and it becomes more difficult to build that level of richness, detail, and insight into my work. I am constantly referring to a vast library of reference material instead of looking into my own brain for the answers.

The solution to this isn’t an easy one. Who is to say that, if we give up our mobile computers and our storage clouds, the faculty of memory will improve to compensate? I’m not even sure I want to: perhaps only the truly gifted can replace organised notes with their memories. In any case, the days of writing by hand and sole reliance on the powers of thought are long gone, for good or bad, and in the future cloud computing will increasingly invade the world of the writer, both for the act of writing itself and the way our books are presented to the world.

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.