The quest for the sublime in the Alps

In this blog post I’d like to talk a bit about how I’m trying to connect the late 18th / early 19th century concept of the ‘sublime’ (and by extension, Romanticism) with my work. First, some definitions. According to Wikipedia, “the sublime (from the Latin sublīmis) is the quality of greatness, whether physical, moral, intellectual, metaphysical, aesthetic, spiritual or artistic. The term especially refers to a greatness beyond all possibility of calculation, measurement or imitation.” Romanticism was an artistic, literary, and musical movement that reacted against the scientific rationalisation of nature, preferring the human response of strong emotion to a natural stimulus. Romantic art (in all its forms) is bold, striking, chaotic, and champions human feeling and awesome natural forces.

These concepts are inextricably linked to mountaineering, far more than most modern climbers would like to admit; indeed I strongly suspect that, were it not for the Romantic artistic movement, mountaineering would never have begun as we know it today. In many ways climbing a challenging peak is the perfect epitome of Romantic philosophy: the bold hero, naked before the terrible splendour of nature, wins to the top by the strength in his limbs and the cunning in his mind–or dies in the attempt. Early mountaineers drew strong parallels between climbing and warfare, and also between climbing and art, which I think is very telling. For many climbers in the early 19th century, the ascent of a major peak was both a mortal struggle and a process of the most profound revelation.

|

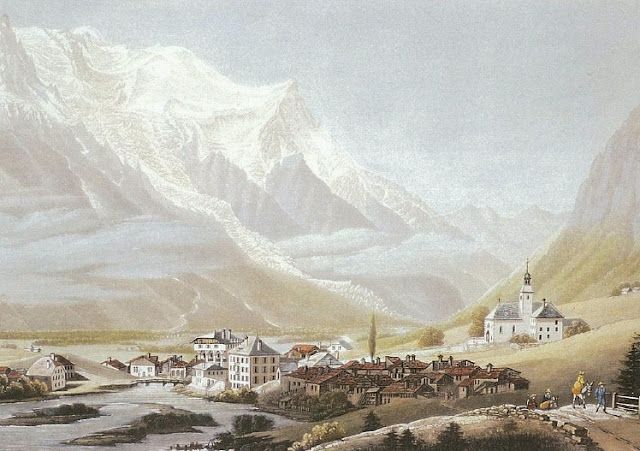

| Chamouni in the early 19th century |

During my time in the mountains I have always been aware of the concept of the sublime, and I have long admired Romantic art and music, but I have never successfully linked it to my writing until now. The Only Genuine Jones is of a different time and Romanticism was starting to lose relevance in the late 1890s, as climbers tamed their environment through the media of lists, guidebooks, and grades. Climbing had lost its aura of dazzled reverence before nature and gained a more scientific approach to the craft of climbing mountains. I think my book strongly reflects that shift in thinking, but personally I have always identified more strongly with the Romantic way of looking at the mountains, so it’s only natural that eventually I would look for a way to explore the sublime in my work.

|

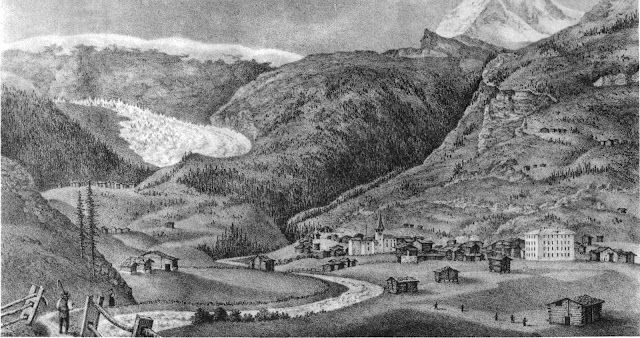

| Zermatt in the mid 19th century |

I’m inspired by Alpine artwork from the early 19th century. The two pictures above are painted by different artists in different years, but display striking similarities. In each, a small human settlement–primarily agricultural and traditional, but each showing the march of Alpine tourism in the form of hotels–nestles amid pastoral beauty. Rustic figures stride along a road next to a glacial torrent. Above it all, the awesome mountains frown down, sending their armies of ice to crush the puny habitation. The fear of the advancing ice was widespread in the early 19th century, when it was widely believed the glaciers would one day grow large enough to destroy the homes of the villagers. They are now in retreat and the level of the ice is much higher than it was two centuries ago.

These paintings are Romantic because they show humanity to be small and feeble, yet also brave and heroic in living out their lives in such places. Nature is shown as vast and all-powerful, at once splendid and also capable of crushing humanity at whim. This reflects the harsh reality of early 19th century life in the Alpine valleys, before tourism really caught hold and provided a more affluent life for many locals. It also perfectly sums up the attraction of the Alps to the early explorers: this was an alien land with alien laws, which provided an irresistible lure for the explorer who dared to dream.

In Alpine Dawn, I am exploring the concepts of the sublime and the Romantic artistic movement, and how these concepts interacted with mountaineering. It’s certainly a more complex theme than anything I have used in my previous book, and I suspect will require a longer story to tell; I want to juxtapose the harsh reality of industrial life with the often harsher reality of Alpine life in the years immediately before the great boom of exploration in the 1850s. To the reader, Victorian London may be a familiar place but I want to challenge preconceptions about life in the period, and show it wasn’t all about cheerful chimney-sweeps, arrogant Earls and struggling journalists. In Europe, thousands of people still lived an agricultural life scarcely changed since the Middle Ages. The concepts of Enlightenment and Romanticism had not yet penetrated these remote Alpine valleys. It’s likely that many peasants had never even heard of the French Revolution or the Napoleonic Wars. It really was a lost world, and learning about it has obsessed me for two years ever since I visited Evolene, the remote capital of Val d’Herens. Since then the work of James Forbes has brought it to life, and I want to bring some of that magic into my own fiction.

So my new book is going to be quite different, and yet I hope it will provide a challenge to the existing genre of mountain fiction. This is not a story about climbers and their rivalries: it’s a story about two different worlds and the remarkable journeys that take place between them. Ultimately I think it will champion the best thing of all about Romanticism: hope and eventual triumph.

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.