“Breaching the Fortress” by Harold Raeburn: a companion article to OGJ

This is a fictional article I wrote some years ago as backstory for The Only Genuine Jones. It features a snapshot of the extended universe I have created for the story: a second attempt at the “Great Wall” of Ben Nevis (the Orion Direct route, in reality not climbed until 1960). It is written in the style of mountaineering articles commonly submitted to climbing journals in the late 19th century.

On Wednesday the 14th of April, after a fortifying late breakfast in the Alexandra Hotel, my companions and I departed from our base in Fort William. Accompanying me was my dear friend and old campaigner, Gregory Dean, the man who they say has never failed on a climb; and a new acquaintance, one Mr P. Earlham, a fellow SMC member who happened to be in town at the time and expressed willingness to join our venture. We employed the services of Mr MacDonald of Glen Nevis, who often conveys supplies to the Observatory with his ponies, to drive a portion of our own equipment as far as the strath beneath the North Face of Ben Nevis.

Our goal was to further reconnoitre that vast sweep of snow and ice rising out of Tower Gully directly to the summit of the mountain. It is, to my knowledge, the steepest ice face in existence in Scotland, and it is perhaps not surprising that O.G. Jones named it “The Great Wall” after his partially successful attempt on the 21st of February this year. The Great Wall remains the most compelling challenge to any ambitious British climber, since no direct passage has yet been made.

As we ascended the pony track up the flank of the Ben, MacDonald prattled away constantly on all manner of subjects, repeatedly turning to the dangers of the mountain. He stressed the ghastly manners in which Observatory men had perished high on the hill: falling from precipices, avalanche, death from cold, heat, even lightning. I have not yet heard of any Observatory men falling prey to the perils of the mountain, and am inclined to believe that MacDonald was merely attempting to impress his charges; nevertheless, the constant stream of mumbled warnings and curses were enough to disturb my peace, and I began to wish I had never thought to engage the irksome man.

We reached the lochan that lies dark and forbidding between the bulk of Nevis and its lowly satellite, a hill known as Meal an t Suidhe. The pony track curved off right up the hill, but our road led us onward over the bog, where a faint path pointed the way to the cliffs. MacDonald drove his malcontented pony onwards with increased reluctance now that the safety of his familiar track had been abandoned.

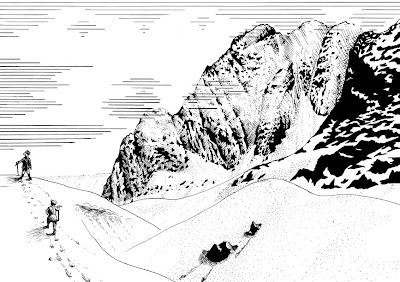

As we dropped down the hill and veered right once again, the precipices began to come into view, one by one, laced with ice and shining in the blue sky: Castle Ridge, the Castle, then the great overhanging buttress coming down from Carn Dearg; finally Tower Ridge and the NE Buttress. MacDonald, now overcome by his fears, declared that he would go no further. He dumped our supplies in the bog and fled.

We were troubled by no such superstitious fancies. The North Face of Ben Nevis is the mightiest scene of mountain grandeur in the Highlands, a genuine paradise for the climber, on which he may spend a happy lifetime exploring to his heart’s content. Routes both easy and extremely hard may be found here. To any genuine Scottish mountaineer, it is the best cliff we have at our disposal.

After establishing our camp next to a level section of slabs where the cliffs may be viewed to full advantage, we spent the evening testing our skill on the many large boulders to be found in the vicinity. We retired early.

Next morning, we awoke at five o’clock and made a hurried breakfast. After making final adjustments to our equipment we started up the lower confines of Tower Gully by the light of the full moon.

At the foot of the wall, where the snow steepened and rose up and up in an unbroken pane of ice, we had some discussion on what the order of climbing should be. The party could be best described as mixed in terms of equipment. Mr Earlham carried a traditional long ice axe and did not own any claws at all; Gregory had just bought a new pair of the Eckenstein ice claws, and carried the combination of long báton and short hatchet that is once more becoming popular amongst Continental ice climbers; and I, of course, being a Progressive man, carried Holdstock ice axes and claws of the first generation. It was immediately clear that such an imbalance would cause problems if I were to lead, as is my habit, for there would be no holds available for my friends. We decided that Gregory should lead.

With his short hatchet, Gregory had a distinct advantage. I am inclined to believe that this hybrid of old and new styles of climbing ice (namely: the wearing of claws for security, while cutting steps with a lightweight short axe) is almost to be preferred to the two-axe style in certain situations. Gregory climbed the first pitch swiftly, but soon began to complain of the awfully long amount of rope he had run out without coming to any satisfactory place to belay. I told him to make do, and after some recriminations which were shortly seen to be wholly deserved, he made the best of the situation.

When I came up to his level, I found that Gregory had buried his báton in a ledge of frozen snow and secured it there with his axe. To this unstable assembly he had tied himself with a length of doubtful cord. Gregory looked upset by this state of affairs, and I felt sorry for my cavalier attitude earlier in the day. There would be belays, I had insisted; the wall could not be as smooth and featureless as it had seemed. I was wrong!

Upwards. Gregory valiantly coped with what was assuredly the most difficult bit of leading he had ever done. The main challenge we faced was the utter futility of the rope: it served no real purpose for safety, as none of the belays were any good. On one occasion when Mr Earlham led a pitch, his nerves failed him about ten feet above my head when he was poised on a tiny nail-scrape and fully stretched out, gripping a natural feature in the ice with his woollen mittens. I was convinced he was going to fall off, but although I have seen evidence of these wonderful axes holding falls before, I did not relish the prospect of thirteen stones of grown man descending upon my head from a height of ten feet. Gregory, with his remarkable calming powers, talked to Mr Earlham until he had composed himself and felt well enough to continue.

We climbed perhaps eight or nine pitches in this manner. Our position became increasingly exposed, increasingly committed. Retreat would have been utterly impossible. Always at the back of my mind was the memory of Jones telling me about his terrifying climb back down to the belay after his fall, close to this very place. He is one of the luckiest men alive to have survived such a fall, in such a grim place as this, and I knew that if any of us were to fall or even to lose heart, we would never be able to retreat. Away to the left, the white ribbon of Elspeth’s Ledge represented an escape to the relative safety of NE Buttress. This is the route that Jones and Miss Mornshaw had taken in February after their dance with disaster. Despite the doubts of my companions, I was resolved that we would not follow their footsteps. We would win through to the top.

Above, a bewildering barrier of rocks, encased in ice and buried in snow, confounded our efforts to find a route. Mr Earlham now felt happier in the lead, delicately scraping steps across the iced slabs and patches of hard snow. Despite the severity of the climb as a whole, I was happy to find conditions as near perfect for climbing as I had ever encountered on Nevis. Every rock was coated in thick, reliable ice. The great slabs in this upper section of the wall were found to be much friendlier than they looked.

As the day slowly ticked away, we became lost. Mist drifted in and shrouded the mountain. A confusion of bastions, turrets, chimneys and corners reared up all around us, and eventually I am sorry to say Gregory and I quarrelled at some length on the question of whether or not we should commit our efforts to one particular smooth-sided chimney. I declared it would go; he was quite rightly becoming unnerved, and refused to climb it. Mr Earlham had become uncommunicative by this point, but soldiered on nevertheless.

We could not find a direct way through the defences of this great fortress. I believe a direct route is both logical and possible, for the right team on the right day, but that happy coincidence was not with us and we elected to circumvent the main difficulties. Our traverse off to the right, up a straight-sided ice chimney and steep face, was difficult enough but very much an escape route.

The summit of Ben Nevis was won at just before seven o’clock in the evening, and after a brief stay at the Observatory for tea and conversation with the staff there, we descended the Arête to Carn Mor Dearg and made the long glissade back to our tent. Each man was quiet with his thoughts. Gregory, I knew, would be cursing himself at his lack of heart. I do not have the privilege of an intimate acquaintance with Mr Earlham, but from correspondence with him after the climb I have been able to ascertain that his views on mountaineering were changed forever by our day out on the Ben. For my part, I had again tasted the bitter-sweet victory that exceptionally hard routes could give to those who dared to seek them out. I felt lucky to be alive, yet privileged to have been to that forbidden place where few had ventured. I felt the satisfaction of exercising my skills.

What have we achieved? Nothing of note. The direct way up the Great Wall remains to be discovered. Yet, in our own small way, I hope that our ‘Fortress Route’ adds a little to the body of work being compiled on the exploration of our greatest mountain, and perhaps the account I have given here will help to prepare the next team to answer the challenge.

Some final points I wish to share :-

1. The maximum angle of ice we encountered felt vertical at the time, but from subsequent observations cannot have been in excess of 80 degrees. It was sustained at 60 or 70 degrees for long stretches. This is ice climbing of an exceptionally severe standard, and yet it must be stressed that our forebears have climbed steeper ice than this for generations in the Alps, using more primitive equipment. On the Great Wall, the danger comes from the length of the route, the exposure, and the lack of any obvious route.

2. A long rope should be considered critical for this undertaking. We took two ropes of sixty feet between a party of three, and this was found greatly wanting, given the lack of belaying places. One hundred feet between each man is required, even though this drastically reduces the safety of the leader.

3. Although our ascent proved that it is possible to climb this route using the old technique of cutting steps, it was found that a short ice axe permitted more precise cutting on the steep first part. More importantly, it reduced fatigue. Our ascent also proved, by direct comparison, that a lack of ice claws puts one at a distinct disadvantage on this sort of ground.

4. Retreat is impossible, and falling off must be avoided at all costs. Aspirant Great Wall climbers must be certain of their abilities, confidence, and the conditions before setting out.

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.