The Ice World

|

| Mountaineers begin the ascent of Mont Blanc du Tacul, dwarfed by the ice world all around them. |

It’s strange to think that water, the compound essential to human survival, can coalesce and twist itself into the fantastical shapes and structures that clothe the world’s greatest peaks.

The Alps weren’t always as they are today. For centuries, people had used the high Alpine passes to trade between valleys, but since ancient times until the 18th century many passes were free of ice. Then the climate changed, and the ice came back.

One by one, these high trading routes became more dangerous each year. They grew wilder, less frequented. Finally they were the domain not of ordinary traders, but the desperate and hardy: smugglers, chamois-hunters, crystal-gatherers, and customs officials who lived in the most abject squalor, often more miserable and degraded than the criminals they pursued.

The Alps were a world of their own. Outsiders rarely went there, and if they thought about the snowy heights at all, it was with a sense of superstitious dread. Dragons, monsters, and the spirits of the damned haunted the unknown regions.

Then, at the close of the 18th century, a quiet revolution was begun by one man: Horace Benedict de Saussure.

|

| The monument to De Saussure and Balmat. They stand in Chamonix and point to the summit of Mont Blanc. From http://goo.gl/75PKI |

This Genevan scientist voyaged deep into the forgotten interior of the Alps. He visited obscure communities such as Chamouni (Chamonix) and Praborgne (Zermatt), places which had survived alone and isolated for many years. This lost world of pastoral beauty and innocence was untouched by the modern era, and he was fascinated by the honest simplicity of the peasants he met there. Religion, language, customs, and way of life were all alien to outsiders. De Saussure explored many of the glaciers and passes connecting the Alpine valleys, but he had one ambition above all others: to achieve the pinnacle of Mont Blanc.

The first ascent was made on the 8th of August, 1786, by Doctor Paccard and his guide Jaques Balmat, but De Saussure’s planning made the ascent happen. He stood on the summit of Mont Blanc himself in 1787.

De Saussure’s extraordinary achievements, in a very different world before the French Revolution, seem almost unbelievable from the distant perspective of 2012. Today, thousands of climbers reach every summit in the Alps each year. Almost every possible route, easy and hard, has been climbed many times. The years of exploration and discovery have receded into the legendary past of our sport.

But the ice world remains.

Picture the scene. You are half way up the immense North West Face of Mont Blanc du Tacul. This mountain is a satellite of Mont Blanc; its summit is 4,248m above sea level, and it is relatively accessible from Chamonix via a cablecar to the nearby summit of Aiguille du Midi. You have to get the first lift to climb the face early enough to avoid the dangers of avalanche, rockfall, softening crevasses, and thunderstorms. About two hundred people have had the same idea as you and the Midi station is absolutely packed when you disembark.

The queue goes all the way up the NW Face. The route is not difficult; to a modern climber it’s basic snow and ice climbing, maybe with a crevasse or two to negotiate. A lot of the time you find you have to slow down because of the slower people in front. It would be easy to get frustrated and compare it to a busy day on Snowdon, but if you find yourself annoyed by the crowds and the shouting, I would urge you to stop, look around you, let the human din fade into the background, and soak in the atmosphere.

You are right in the middle of the ice world. All around you, water is contorted and folded into the most spectacular and fantastic forms imaginable. Crevasses seam the slopes, jaws ragged with icicles, opening just wide enough to show the dark pits that reach deep into the mountain; who knows how far down they go? Sunlight hits a slope of snow, and a stream of loose material avalanches off, dashing itself to pieces on splintered pinnacles beneath. You pass below a serac, moving quietly and quickly because these are places of danger. The tottering pile of ice could collapse at any minute and wipe out a dozen climbers. It has happened before many times, and it will happen again; this is a lottery, but one that we willingly play.

Touch the surface with your gloved hand. The ice is built up in layers, like the trunk of a tree: transparent glass alternating with granular matter in wonderful shades of green and blue. The textures and colours are easy to miss when you wheeze past in a clanking column, eager for the next tick. The urge to climb fast and stick to guidebook time is deeply ingrained in the modern Alpinist, but sometimes it pays to slow down and try to look at the wonderful ice world through the eyes of a child. This is how the pioneers viewed this environment, when they knew they were among the first to see it in the flesh. Danger is always present, but there are no monsters or demons, only unparalleled natural beauty.

|

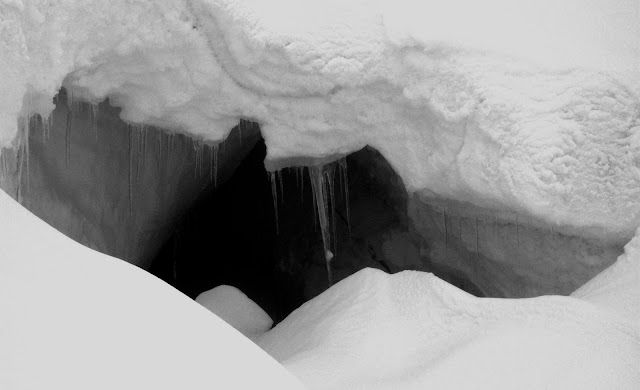

| A crevasse |

Today, the glaciers recede in a warming climate. Perhaps in time the passes will resemble their condition in the 17th century, and easy travel between valleys will once again be possible. For now, ice clothes the mountains and climbers play the great game of peaks, passes, and ridges. From a time of bold exploration in an obscure hinterland peopled by ghouls and unknown dangers, mountaineering has become, for many, a game of numbers: peaks ticked off a list of 4,000m giants. In our rush to climb the peak and get back down, not all of us take the time to appreciate how lucky we are.

The Alps as we know them won’t be here forever. In twenty years, glacial retreat may have made many summer routes too dangerous. Even if summer Alpinism survives in its present form, the splendid ice world as we see it today will have diminished, become dirtier and rockier. Some glaciers may die altogether. We must look around us and see all we can while it is still here.

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.