19th century glacier travel – a brief analysis

Before the summits of the Alps could be reached, terrain arguably more hazardous than the upper slopes themselves – and certainly less predictable – had to be negotiated. A frozen raiment guards the greatest peaks of the world, and two centuries ago this mantle of ice extended deeper into the valleys than it does today. The rampaging ice crushed villages, terrorized citizens, and presented formidable barriers to early explorers.

Such a place is called a glacier, and the history of glacier travel is central to the history of mountaineering as a whole.

The hazards

|

| The Brenva Glacier, Mont Blanc, in 2008 |

As you can see from the photo above, glaciers often present a baffling confusion of holes – called crevasses or schrunds – caused by stresses beneath the surface. The substance of a glacier is continually moving downhill (a process documented and explained by my character James Forbes in 1842) and the varying terrain beneath the ice itself is mirrored in the pattern of crevasses on the surface. Twists and turns in the flow, and constrictions or widenings, also have an effect. Crevasses vary in depth from a few feet to many hundred.

Crevasses are never the same from one year to the next, and therefore any effort to map a consistent path through a crevasse field is futile.

There are two regions on a glacier. The ‘dry’ region further down is characterised by bare ice, ablated by the action of the sun and water, and crevasses are obvious. The higher ‘wet’ region is carpeted with snow of varying thickness, and travel is complicated by the presence of snow bridges whose stability varies with the time of year and hour of the day. Many crevasses will be entirely hidden under the snow and present deadly traps for the unwary. For these reasons a wet glacier is generally more dangerous than a dry one, although at a glance it may seem to offer a less complicated route of ascent.

Crevasses vary in size from little slots to gaping monstrosities. If the climber falls into big a crevasse, he might get stuck in a constriction or fall to his death. Only a rope connecting him to a companion, and the means to extract the climber from the hole, will prevent a fatal accident. As I’m sure you’re beginning to see, planning a safe route through such terrain is a significant challenge.

Modern glacier travel

|

| The author kitted out for glacier travel |

Today, climbers have access to a wealth of equipment and knowledge specifically developed to keep them safe while crossing glaciated terrain.

Ropes

Climbing ropes are incredibly strong, lightweight, never break when used correctly, and generally 50-60m in length. They are flexible enough to be easily knotted and unknotted, even when frozen (which rarely happens, as most climbing ropes are specially treated to avoid freezing). They are smooth enough to work properly with belaying equipment but grippy enough not to slip through the hands.

Hardware

Modern glacier travellers have stiff boots, lightweight crampons, and ice axes used for a variety of tasks including aiding traction, arresting falls, and as an anchor. Lightweight aluminium karabiners, ice screws, and snow stakes make it easy to set up anchors. Pulleys and Prusik loops enable us to set up hauling systems if required. Most climbers will choose to wear a helmet to protect the head in the event of a fall.

Techniques

During the 20th century a range of techniques were devised to both prevent falls into crevasses and to extract the climber if and when a fall occurs. In the picture above I am wearing a number of rope coils, both to shorten the rope between me and my partner and to give me some rope to work with in case I need to build an anchor. The ‘live’ end of the rope is tied off to my harness with a Prusik loop to isolate the coils and concentrate force in the correct way. If my partner were to fall into a crevasse, I would fall on my front and dig my ice axe into the snow, arresting the fall, before building an anchor to take the strain away from my body. This would then give me the freedom to set up a hauling system using pulleys, karabiners, and Prusik loops to aid my partner in climbing out of the crevasse. Experience has also taught me how to identify safe snow bridges, and even how to spot the telltale signs of crevasses completely hidden beneath the snow.

An informative video from the Mountaineering Council of Scotland detailing crevasse rescue can be viewed here.

These systems are learned and practised by modern climbers who venture onto glaciers. They were developed after decades of far more rudimentary methods – methods which had a far smaller margin for error, sometimes resulted in the deaths of those who used them, and yet (surprisingly) often did the job.

Glacier travel in the 19th century

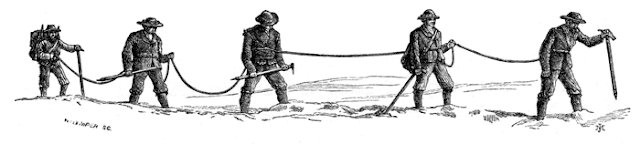

The picture above dates from the 1860s, a period in the late ‘golden age’ of Alpine exploration. In this era climbers often invented techniques on the spot, and there were no agreed safety standards whatsoever. However, men like Edward Whymper had begun to turn an analytical eye towards safety techniques, and a few basic principles had emerged: safety in numbers (the more people on a rope, the easier it is to pull someone out); never cross a glacier without a rope; keep the rope between climbers short and taut; glaciers are safer early in the day or at night; and finally, experienced climbers knew how to identify hidden crevasses and safe snow bridges.

Twenty years before, these principles were either unknown, or applied only haphazardly. The mid-1850s boom in Alpine climbing helped to accelerate the development of safety techniques.

Ropes

Until scientific methods were first applied to the testing of climbing ropes in the 1860s, the ropes used for mountaineering were of dubious quality. They were hawser-laid, often made of whatever material came to hand. Some would hold the weight of a man, others would snap easily. They were stiff, weak when wet, and froze into solid cables. Tying knots was a difficult task even when the rope was in perfect condition.

Hardware

Modern climbing hardware simply did not exist. Rudimentary crampons were popular in the first two decades of the 19th century, but by the late 1840s they had largely died out. Most travellers wore simple hobnailed boots; some of the earlier and poorer chamois-hunters-turned-guides wore smooth-soled wooden clogs.

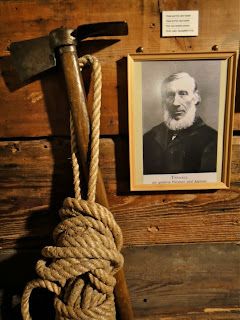

|

| Relics from 1888, found on the Weisshorn |

None of the karabiners, pulleys, Prusiks, slings, or harnesses we use today existed. Climbing hardware began and ended with the ice axe, an invention of the 1840s – 50s when Chamouniard guides thought to combine the ice hatchet with the baton or alpenstock used in previous decades. Early ice axes were mainly used for chopping steps and were absolutely useless for arresting a fall. In fact, there was no standardised pattern in axe design until Edward Whymper invented the format we use today. One major advantage these older axes had was the extreme length of the shaft: a property that made it far easier to probe snow bridges and seek crevasses hidden beneath the surface.

|

| A typical early ice axe |

|

| John Tyndall’s ice axe |

|

| The Whymper axe. Note the pick and horizontal adze, features which aid self-arrest. |

Techniques

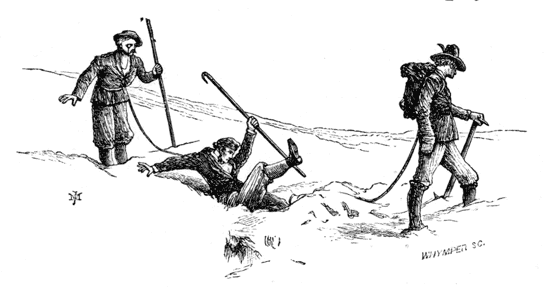

As I’m sure you can imagine by this point, if you fell into a big crevasse in the 19th century then getting out would be difficult.

Picture the scene. You suddenly break through a thin crust of snow and fall into darkness. On the surface, your companions are struggling to hold you, some of them plunging their axes into the snow, others flat on their faces being dragged in themselves. If they don’t manage to arrest the fall then chances are everyone on the rope will be pulled into the hole and killed. Even if they manage to hold the fall, you aren’t wearing a harness so the loop of rope around your waist is gradually crushing the breath out of your body.

Now your companions are faced with the challenge of getting you back to the surface without the aid of anchors or pulleys that can be used to create a hauling system. This is why glacier travel was often conducted in larger groups: more muscle to help pull out a stricken man, and a greater chance of holding the fall in the first place.

If the crevasse is shallow or narrow, or at an angle which lets you partially climb back out, the job is made easier. If you are dangling in space with no way of assisting the hoist then you’re in big trouble. There is also no mountain rescue, so you can expect no outside help.

Such situations were frequently lethal. Perhaps not surprisingly, most of the glacier travel techniques of the time were oriented towards prevention rather than cure, and experienced climbers became very good at avoiding hazards and navigating complex routes across crevassed terrain.

Some contemporary sources

From Glaciers of the Alps by John Tyndall (1860):

“Three or four times he [Bennen] half disappeared in the concealed fissures, but by clutching the snow he rescued himself and went on as swiftly as before. Once my leg sunk, and the rink of icicles some fifty feet below told me that I was in the jaws of a crevasse; my guide turned sharply – it was the only time that I had seen concern on his countenance :- “Gott’s Donner! Sie haben meine Tritte nicht gefolgt.” – “Doch!” was my only reply, and we went on. He scarcely tried the snow that we crossed, as from its form and colour he could in most cases judge of its condition.”

From Scrambles Amongst the Alps by Edward Whymper (1871):

“[Some] Guides object to the use of the rope upon snow-covered glacier, because they are afraid of being laughed at by their comrades … We arrived at the edge of the ice, and I requested to be tied. My guide (a Zermatt man of repute) said that no one used a rope going across that pass. I declined to argue the matter, and we put on the rope; although very much against the wish of my man, who protested that we should have to submit to perpetual ridicule if we met any of his acquaintances.”

“I believe that the unwillingness to use a rope upon snow-covered glacier which born mountaineers not unfrequently exhibit, arises – First, on the part of expert men, from the consciousness that they themselves incur little risk; secondly, on the part of inferior men, from fear of ridicule, and from aping the ways of their superiors; and, thirdly, from pure ignorance or laziness.”

“I often meet, upon glacier-passes, elegantly-got-up persons, who are clearly out of their element, with a guide stalking along in front, paying no attention to the innocents in his charge. They are tied together as a matter of form, but they evidently have no idea why they are tied up, for they walk side by side, or close together, with the rope trailing in the snow. If one tumbles into a crevasse, the rest stare, and say, “La! What is the matter with Smith?” unless, as is more likely, they all tumble in together.” (Note: today this is known as “death-roping.”)

From the Badminton Book of Mountaineering by C.T. Dent (1892):

“The process of extricating the temporarily absent friend must be conducted in a methodical manner. He will not be got out by hauling vigorously at him from both sides, though he may be partly suffocated by this proceeding. Firstly slacken the rope a very little. The submerged man will often then be enabled to work his way up again through the hole by which he entered, or can break down the edges and widen the gap, and so make a way out … The rope, in fact, cannot do much more than give him material assistance, and he will have to do the major part of the work for himself.”

“Guides do not always show much method on these occasions. They exert themselves with a hearty good will, it is true … Too often guides will pull until they can pull no more.”

“If he is suspended in mid air, or finds only soft loose snow to support his feet below, the difficulty of getting out will be very considerable.”

“On a dry glacier only extreme carelessness … could lead to any accident … and it will not be found very difficult to extricate a man directly from any fissure into which he may have chanced to fall.”

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.