Ditching the infinity machine — five months later

Chris Townsend has written a very interesting response to this article. I urge you to check it out.

In October 2014, I wrote about how I felt taking my smartphone with me into the hills was spoiling my enjoyment of being in the wild. The resulting article struck a chord; it remains one of the most popular pieces on this site, and many people chose to leave a comment or contact me on Twitter to convey their thoughts on my decision to stop using my smartphone.

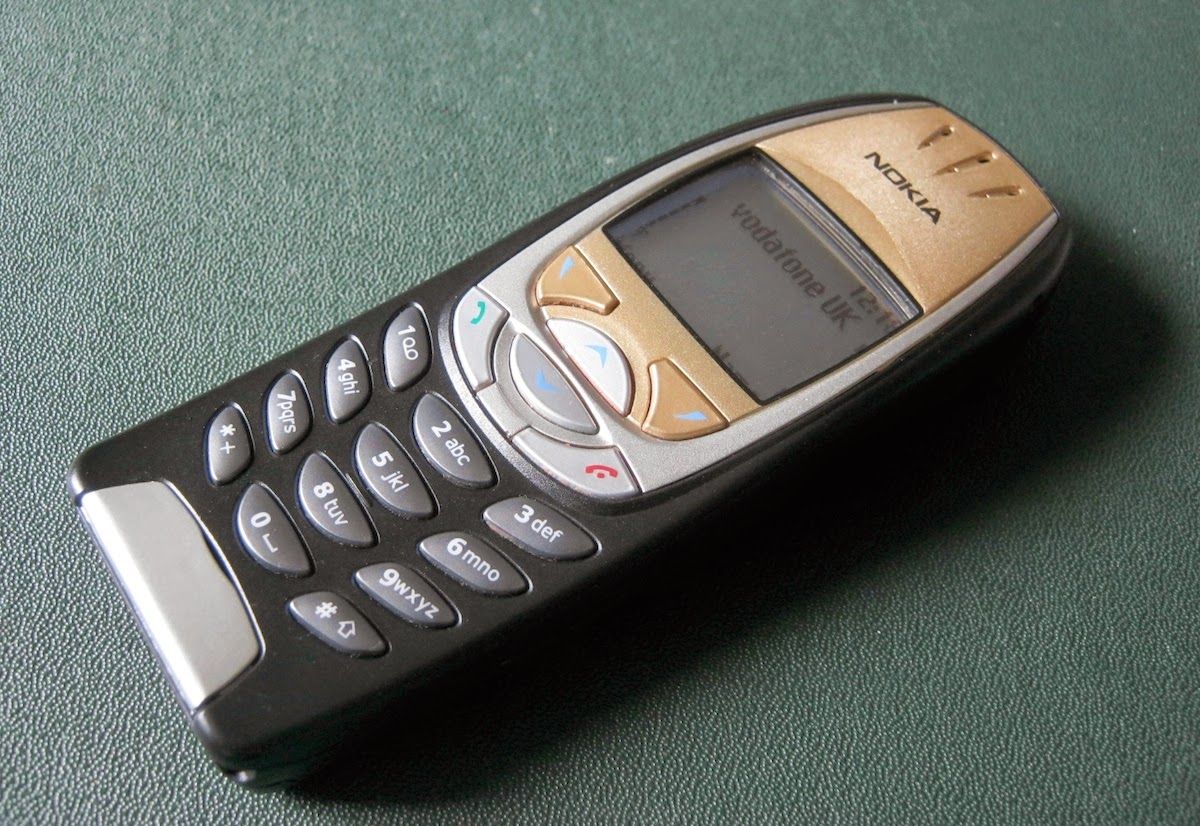

At the time, I thought that my irritation with using a smartphone — both in the hills and in general life — stemmed from over-reliance on technology, and the atrophy of analogue skills and processes I had once enjoyed. So I started an experiment. I bought a Nokia dumb phone.

Phase One: The Brick

My dumb phone of choice was the Nokia 6310i from the year 2002. Yes, that’s right — I went full retro.

The first few days were a mixture of freedom and minor adjustments. In my pocket I no longer carried the infinity machine that had begun to feel like a burden; instead, I carried a piece of antique hardware that was capable of performing only two tasks: making calls, and communicating via text message.

Despite the limitations of the hardware, the Brick performed both of those tasks extremely well. It was comfortable to hold during calls (something many modern phones fail miserably at), audio quality was superb, and the keyboard was a pleasure to use. I could type faster on the damn thing than I could on the touchscreen of my iPhone. At first, the battery life went on and on.

Fantastic, I thought. I have broken free of the shackles of twenty-first-century life! The experiment felt incredibly self indulgent (what one might call a first-world problem) but I was determined it would be worthwhile.

I combined the Brick with a pocket notebook, digital wristwatch, film camera, Garmin GPS, and my old iPod. For a few weeks things were great; I was undisturbed by the endless pinging of notifications, my attention span was recovering, and if I needed to use a computer I … used my computer. Of course, the truth is that I work from home so am at my desk most of the time anyway; using a dumb phone was no great hardship when in my office.

When I actually left the house, things became a little more complicated.

Freedom from needlessly surfing the Web was great, but I had failed to appreciate how often in modern life one actually has to look something up online then and there. A bus timetable, for example, or a weather forecast. Maybe you’re waiting for an important email and can’t be at your desk for a few hours. Coping without this convenience is something that many of us have forgotten, and it started to feel like needless deprivation after a couple of months.

What about using the Brick in the hills?

I took the phone with me on my less-than-successful Lairig Leacach bothying trip in November. For a couple of days it worked fine: great signal strength, and calling and texting were all I needed. I liked not being able to succumb to the temptation of lazily using my phone for navigation.

Then the battery ran out, much earlier than I had expected. Afterwards I realised that a battery from 2002 is going to have problems.

I had assumed that this Nokia would work with my 13,000 mAh charging unit. This device stores energy and can be used to charge almost any device that takes a standard 5V USB power input. However, even though I had purchased the right cable, the Brick simply refused to charge. It kept saying ‘charger not supported’, and eventually the phone ran out of juice as I was on my way back from Scotland — and travelling in the direction of an almighty public transport cock-up.

I’m well known for my public transport cock-ups. You might say that I’m a connoisseur of the great British rail fail. I’ve been stranded at Peterborough train station more times than I can count — it generally happens a few times a year, and the tradition has been going on for about a decade — and I am notoriously bad at interpreting bus timetables. This isn’t a skill that has atrophied since the onset of the digital age; it’s a skill I have never had.

I hadn’t realised how much my ability to extricate myself from these situations was due to the ability to access the Web on the move.

On my way back from Scotland I found myself not only without access to the Web but also without access to a phone of any kind. I ended up stranded at Glasgow Central, having missed the last train, and vaguely contemplating a night in a bus shelter. I hadn’t been able to find a hotel because I didn’t have access to mapping and I couldn’t find anywhere to buy a paper map that late at night. I managed to call Hannah, my long-suffering partner, on a pay-phone; she got in touch with some friends who swooped in and rescued me just before the station was due to close for the night.

It was a lesson worth learning. When I got back, the Nokia 6310i went into a drawer and hasn’t come out since.

Phase Two: Compromise

My next phone of choice was the simple, inexpensive, but relatively modern Nokia 206.

My rationale for the purchase was that the 206 would allow me to access the internet via the Opera Mini Web browser. It’s a slow and clunky connection, to be sure, but in a pinch it would do the job. I could even read my emails and check Twitter if I wanted, but the connection was so lousy that I wouldn’t be tempted to waste time online. Essentially, I believed it would be the best of both worlds: freedom from distraction and the infinity machine, but also a safety net should the need arise.

The Nokia 206 is actually a great phone. Call quality is loud and clear, I generally get about five days of battery life out of it, and it works extremely well for messaging.

I have used the Nokia 206 quite happily for several months now. It does almost everything I need, but it isn’t a burden in the same way that a real smartphone can feel like a burden. When I took it to the hills in February this year, it performed admirably in areas of poor signal and kept me just connected enough to the outside world without coming between me and my enjoyment of the outdoors. It has no GPS so there is no mapping option.

But…

The thing is, I’ve slowly come to appreciate that the utility of a smartphone is not truly in giving you a portal to the Web, but in replacing other items. For a backpacker this is a big deal. For example, if I take the Nokia 206, I have to also take a Kindle, an iPod, a GPS device, a camera (I’ll come back to this), and the necessary paraphernalia to keep them working (spare batteries or special cables).

I’m currently planning my attempt at thru-hiking the Cape Wrath Trail in June this year, and one of my objectives is to keep my pack weight as light as possible. Originally the plan was to pack the Nokia 206 and take advantage of its stellar battery life. However, the combined weight of the 206 and all the other items I’d need to keep me sane on the trail was not insignificant. I would have to carry the 13,000 mAh portable battery regardless of which device I carried, so the weight of that didn’t factor into the equation.

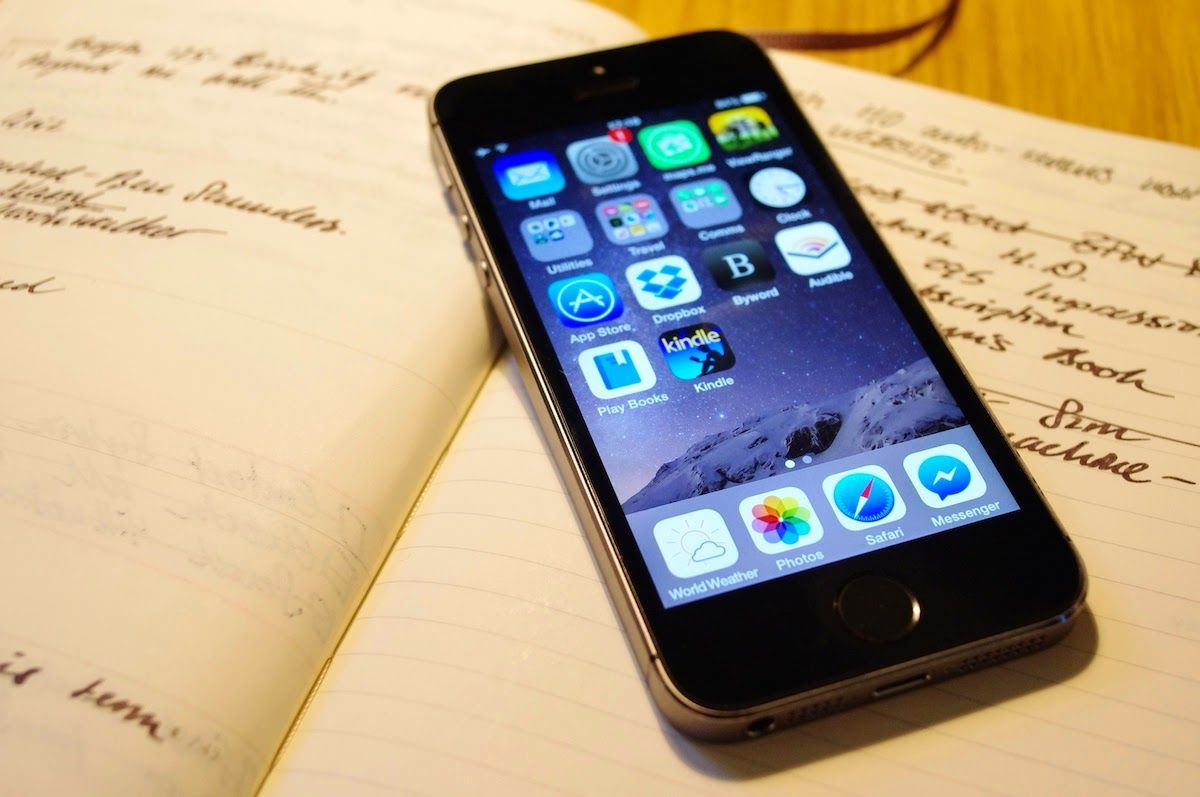

I started to think about things that the iPhone could replace. GPS — that’s a no-brainer. iPod — absolutely. Kindle — this one made me pause, because reading on a small, bright screen isn’t the same; but if I’m going to be ruthless about cutting pack weight then it’s certainly possible to read Kindle books on an iPhone. Camera — this is the only area where I’m unwilling to compromise. I’ve just bought a DSLR and an iPhone camera is simply no substitute.

I did the sums. Taking the iPhone on the CWT with me will reduce my pack weight by almost a kilo. I would have to be an idiot to ignore that kind of weight saving when I’m committed to keeping my base pack weight below 10 kg.

Sometimes the more practical solution wins the day.

Phase Three: Adaptation

I’ve mainly been using the iPhone as a WiFi powered mini-tablet over the last few months, albeit with all notifications disabled and a massively reduced payload of apps. Maybe I’ll only switch it on a few times a day, and it doesn’t always leave the house with me. But the thing is, I haven’t made the step of selling it — because there are certain things it does that are occasionally essential.

Sometimes I need digital mapping when I’m in unfamiliar place and need to get around. Sometimes I need access to certain nineteenth-century texts, digitised and stored in Google Play Books. Sometimes I need to get my email and don’t fancy waiting five minutes for the Nokia 206 to draw my messages from the server. And having a pocket camera is priceless every now and again.

There are, of course, workarounds for most of these first-world problems. But I’ve come to realise that there is often simply no point in jumping through those hoops; that there is no inherent virtue in using a slightly less advanced mobile phone just to make your life a little more difficult or ‘analogue’. It’s all in how you approach the technology. Maybe I knew this all along and needed to try it for myself to realise it.

I find myself gradually using the iPhone more and more, but never as much as I did before. And now I’m planning on taking it with me on the CWT, I’m contemplating ending the experiment and going back to it full time — with certain important changes to my habits.

What I’ve learned

I’ve learned that a phone is just a phone.

What I called the infinity machine is not the slab of metal and glass in your hand. It’s the laziness in your mind that is unable to use the almost limitless capabilities of that hardware wisely.

When you’re bored, it’s easy to look to the infinity machine to entertain you instead of looking around and engaging with your surroundings. Notifications and ‘social’ interactions online provide tiny hits of pleasure that become addictive, feeding into a cycle of craving even as part of you is aware how they disrupt your concentration and ruin your ability to focus on the task at hand. It’s easy to fall into that groove because, after all, everyone is doing it. Maybe you feel you need to use all these apps all the time to be successful; maybe you feel you have to respond to that email right now otherwise the person who sent it will think you don’t care.

The truth I’ve learned is that — for me, at least — my own weakness was the true root of my original discontent, not the phone itself. It turns out that destroying that cycle of behaviour is actually quite easy: remove all apps you don’t need or use, and deactivate all notifications except incoming calls. Be ruthless in trimming the phone down to what you need it to do. Notifications are a subtle poison.

You probably don’t need to reply to that email right away. You almost certainly don’t need any social media apps on your phone; having access to them through the Web browser is enough, and provides just enough friction to discourage you from signing in every minute or two. With notifications gone, your usage will drop naturally. Removing games is another step in freeing up your time and energy for things that actually matter to you.

My iPhone no longer disturbs me when it wants attention. I turn to it when I need it to perform a task; for the rest of the time it lies silent, dormant, without needs of its own. I can use it when necessary and retain my focus. I rarely use it when I’m out and about unless I actually need to. This is more or less what I wanted to achieve with the dumb phone experiment, and I’m pleased to discover it’s possible to do this without giving up the significant advantages of having a smartphone in the first place.

How the experiment has changed my habits for good

I might be back to using an iPhone again, but some of the good habits I adopted during the experiment are not going to be abandoned.

Most importantly, all notifications are going to remain off, and I will be ruthless about only keeping apps that I actually need on my phone. I’m also going to be vigilant about what I use it for. If I find myself listlessly browsing the Web when I should (or could) be doing something more interesting or useful, I’ll go back to the Nokia 206 for a while.

Carrying a pocket notebook was a very positive change back to my earlier way of doing things. In my article on thought processing, I explained how I had somehow drifted into the habit of using a smartphone for taking notes, and felt the desire to change back to pen and ink. It’s just a better experience for me and I will continue to use pocket notebooks.

Wearing a wristwatch is another welcome return to an earlier habit. It’s more convenient than checking the time on your phone, and I have to get my phone out of my pocket less often.

Lastly, I have found a greater appreciation for real photography over the last five months. I’ve used gorgeous old film cameras and now own a DSLR. Before last October my photography was very much of the point-and-shoot variety, but I’ve improved as a photographer largely because I’ve made the effort to carry a real camera around and work a bit harder for my shots. That certainly isn’t going to change, and this has been an especially positive aspect of the experiment.

Conclusion

I’m not here to tell you what you should or shouldn’t do with your smartphone. What I found frustrating about my smartphone use may not trouble you at all, and what worked for me may not work for you. But if you have found yourself wishing you could be a little less connected, or think that you’re spending more time on your phone than you would like, it’s worth considering a change in your habits. Switching to a dumb phone is the nuclear option; as I’ve discovered, all it really takes is being self-aware and making small changes to how you do things.

Smartphones are valuable tools in the modern world. But, like all tools, they can be both used and misused.

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.