Preparations for the Cape Wrath Trail

The time has come to talk a little about my plans for this summer. It’s been ten years since my first long-distance walk in the mountains — a hundred and sixty miles through the Lake District in May 2005 — so I thought it was only appropriate to do something special this year.

The idea came to me back in February, when I was contemplating the snowy Cairngorms and considering a change in direction for my outdoor activities. My interest in Munros was on the wane and my interest in backpacking experiencing a renaissance. Reading the excellent Rattlesnakes and Bald Eagles by Chris Townsend helped to re-ignite that interest in long-distance hiking, and since then I have enjoyed books by Keith Foskett (who is right now walking his first miles along the epic Continental Divide Trail in the USA).

I don’t have six months I can devote to thru-hiking one of the world’s longest routes, but now that I’m self-employed I can certainly arrange a month off work to take on something shorter. I wanted to tackle a walk of decent length, considerable challenge, and passing through truly wild country. In the UK there can only be one candidate.

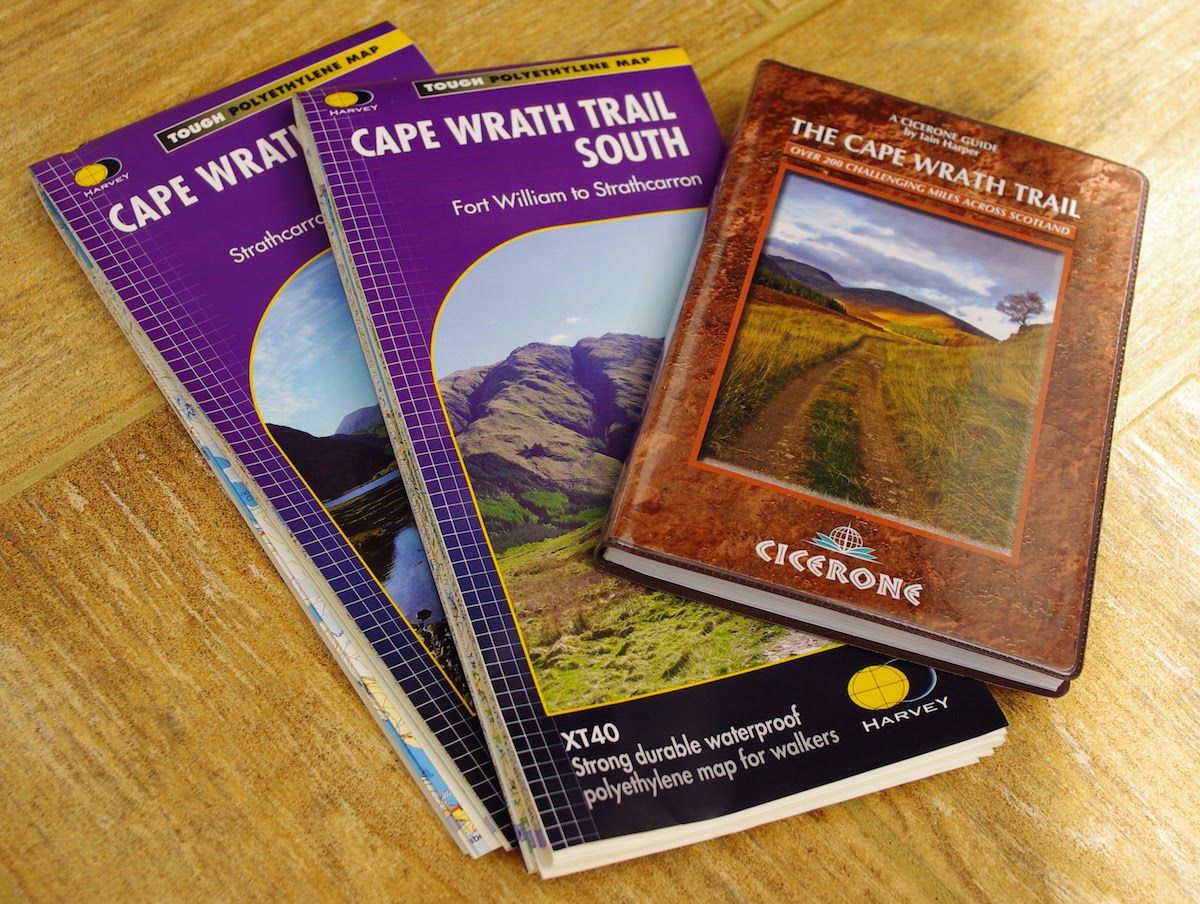

The Cape Wrath Trail

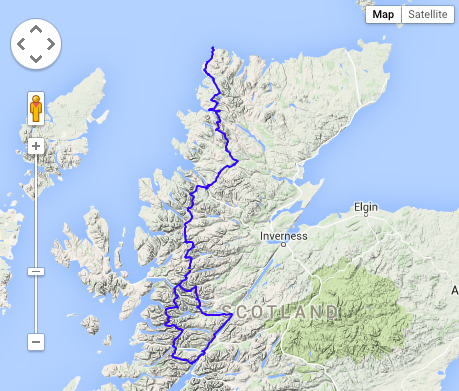

The Cape Wrath Trail is not an official long-distance route. It came to prominence in the mid-1990s due to various publications, but there is no one recognised path, and it certainly isn’t waymarked like, for example, the Pennine Way. The general idea is to make your way from Fort William to Cape Wrath at the farthest NW corner of the UK. Most CWT thru-hikes are approximately two hundred miles in length.

This screenshot is from the CWT page at Walkhighlands and shows two of the most common variants at the start: the Great Glen variant, and the Glenfinnan variant.

I knew at once that the Glenfinnan variant was for me. Not only is it the wilder route, it’s also the most interesting and gives you the chance to trek through the wilds of Knoydart. I have been to Glenfinnan once before but never set foot in Knoydart. The opportunity is too good to miss.

|

| On my last visit to Glenfinnan, in April 2011 |

I have selected the Iain Harper route as the basis for my CWT attempt. I’ve consulted his guide, which offers a number of options along the way, including bad-weather alternatives. The route is continuously superb and takes the hiker to some wonderful locations including Knoydart, Glen Shiel, Torridon, the Great Wilderness of Fisherfield, Assynt, and Sandwood Bay.

I have selected June the 3rd, my twenty-ninth birthday, as the date to begin my thru-hike of the CWT.

|

| Beinn Fhada, from near Morvich |

Preparations: fitness

Fitness is one of the most important aspects of a long-distance walk. I live in the lowlands and have a job that keeps me at a desk for several hours a day, which means that maintaining the right level of fitness can sometimes be a challenge. I don’t get the chance to visit the hills more than a few times a year.

My strategy is reasonably simple, and based on one fact: I enjoy road biking. I don’t take it ‘seriously’ (I don’t own any lycra and my bike is about as old as I am), but the Lincolnshire Wolds are great for long days out on the bike. There are enough ups and downs to get the blood pumping.

I sometimes end up working weekends, but I’m aiming to get a twenty-mile route done at least once every couple of weeks. More importantly, I get out on the bike every morning before work. My circuit is only a couple of miles long, and it only takes me fifteen minutes, but it includes a decent gradient and I have already noticed a significant improvement in my fitness since I started this routine.

Of course, cycling alone isn’t enough. The only real training for carrying a big pack over long distances is, you’ve guessed it, carrying a big pack over long distances. I plan to get out walking as often as I can between now and June, and will hopefully have time for another short backpacking trip next month.

|

| The Forcan Ridge of the Saddle |

Preparations: gear

When I started planning this trip I thought I’d be able to make do with the gear I had. Most of it was five to ten years old, but still serviceable. However, as I planned I realised I would have to make some changes to my kit. Why? It’s simple: my pack was just too heavy, and some items were starting to wear out.

The first thing to be changed was my footwear. For the last three years I’ve been wearing a fairly clumpy pair of Scarpa B1 mountaineering boots for more or less everything, although I’ve dabbled in trail shoes for much longer. I decided immediately that this will be the year I switch entirely to trail shoes for everything except winter and full-on mountaineering. I’ve already blogged about this decision and I’ve started to reap the benefits.

|

| The Inov-8 Roclite 295 shoes |

A critical look at my backpacking load resulted in a number of unnecessary items being removed from the list, including my bivvy bag and various items of clothing. Next I re-appraised my cooking system.

Finally, two of the ‘big three’: my pack and my tent.

Pack

My old rucksack is a Haglöfs Matrix 60, purchased in 2010. The pack has served me well — it’s incredibly tough and holds a ton of gear. I’ve carried 18kg in it on winter backpacking trips. However, a few niggles prevented me from really loving this pack. First, the main clips holding down the floating lid required modification with a penknife on day one (there were random rubber flaps that got in the way). Second, the shoulder straps tend to slip after about ten miles. Third, the hip belt was never really a perfect fit for me, and is not removable on this model. Fourth, it’s a mountaineering / climbing pack so not ideal for thru-hiking, with few external storage options.

I decided to replace it with a ÜLA Circuit 68. ÜLA packs are made in Utah and are specifically designed for long-distance hiking. This model only weighs about 1kg, and I was able to order one tailor-made to my requirements. It’s lightweight, incredibly comfortable, and has a number of features I really like such as the roll-top closure and the massive mesh pocket on the back. The total volume is 68 litres including all the external pockets, but the main compartment is only about 45 litres so the pack is far more compact than my Matrix — but still big enough for the Cape Wrath Trail.

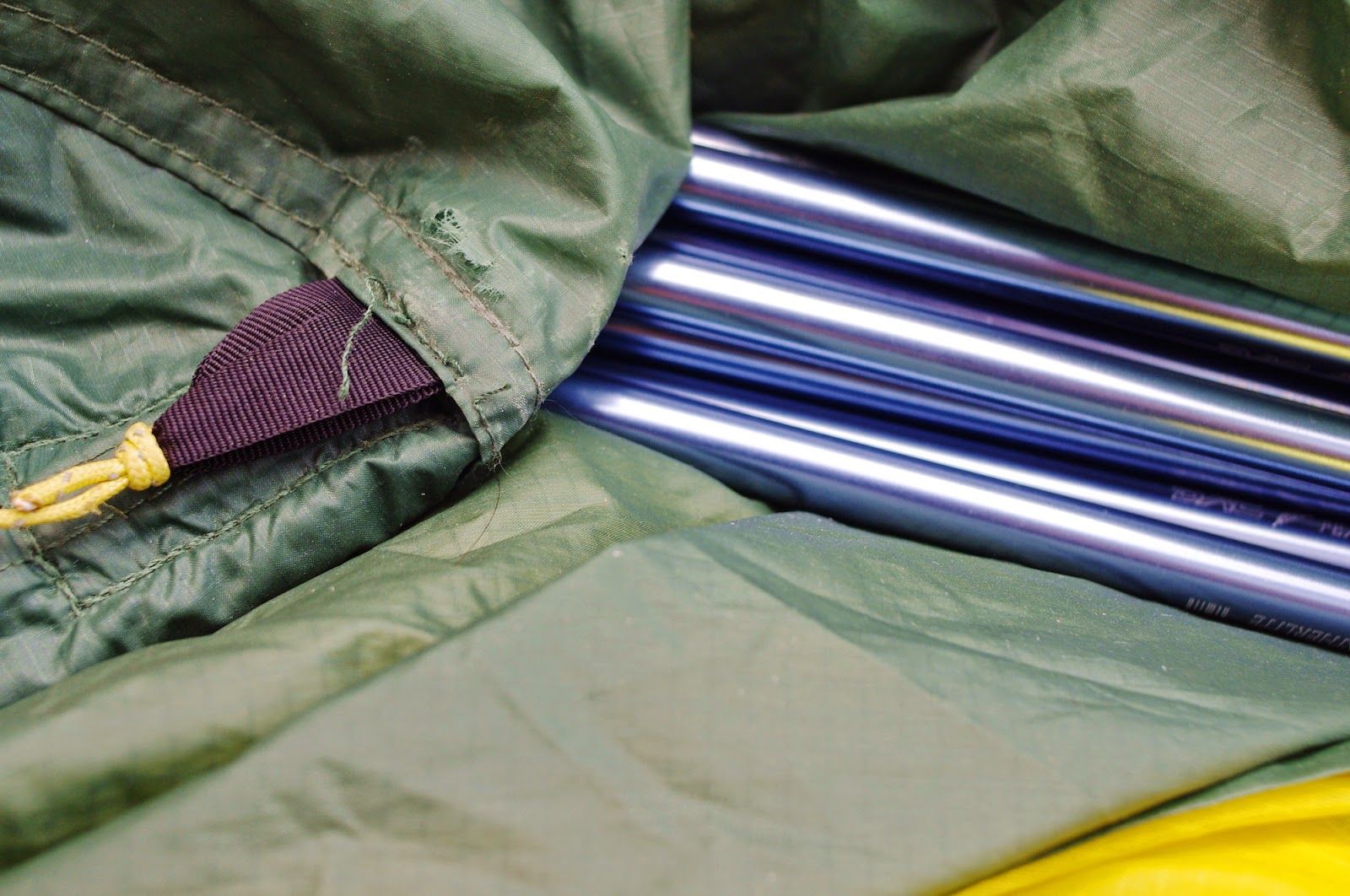

Tent

What about my tent? Since 2010 I have used a Terra Nova Laser Competition, and it’s a fantastic shelter — again, with a few reservations.

|

| The Laser Comp on its first real test: a week backpacking in Jotunheimen, Norway |

I first used the Laser Comp while backpacking through Jotunheimen in Norway. I was battered by some extreme weather on that trip, and although I liked the small pack size and roomy interior of this tent, it was frankly terrifying to sit out a storm in it. You can see in the picture above how I was forced to use my ice axe to reinforce one of the guylines. The supplied Titanium pegs were useless in anything but optimal ground, and I ended up replacing them with slightly heavier aluminium tri-beam pegs. Also, the structure just isn’t that stable in high winds and some big gusts flattened the tent so much that the pole warped and the canvas was blown flat against my body. During one particularly bad gale I had to hold the structure upright with my own body to prevent the tent from being blown into Sweden.

The tent survived some fierce winds on that trip, and after replacing the pegs my opinion of it improved somewhat. Since then I’ve probably spent about thirty or forty nights in it, including a few more gales. The other major drawback of the Laser Comp is that ventilation never seems to be sufficient and it suffers badly from condensation.

|

| Heavy interior icing while camping near Ben Alder, February 2012 |

I was prepared to live with these drawbacks for the CWT, but yesterday I read this worrying article by Terry Abraham about how lightweight tents often accumulate unseen damage caused by repeated stress. He had a Laser Comp at the time of writing, and noted a number of points of wear and tear. Worried, I did a proper inspection of my tent.

To my horror I saw a number of issues I had never noticed before. The main pole was bent — not that big a deal, but more concerning was severe wear and tear in several places on the flysheet.

|

| Wear visible near one of the guyline attachment points |

Ordinarily I’d be happy to slap on some duct tape and carry on, but these are critical points where the flysheet rubs against the top of a carbon-fibre pole and is attached to the bow and stern guylines. I have heard of catastrophic failure at these points for this model of tent, where the short poles split through the fly and the entire structure collapses. There is also wear to the stitching on several other attachment points, not to mention what appear to be friction burns in places where the fly rubs against the pole sleeve.

Full repairs would be costly, and I wouldn’t trust any home-made bodges, so I made the decision to ditch the Laser Comp for this trip and find something else. Preferably something lighter with better wind resistance.

I settled on the Tarptent Notch. This is another American product — they do lightweight gear better than we do — and I think it’ll be perfect for my needs. It is supported by trekking poles (why carry dedicated tent poles when you’re carrying trekking poles anyway?), weighs less than 800g, and is far more stormproof than the Laser Comp. Unlike many shelters designed for American thru-hiking, this one has a full inner tent with bathtub floors — features I’m not yet ready to give up, despite the recent popularity in using tarps in Scotland.

I have yet to receive the Notch, but I’ll be sure to test it out before I start my CWT journey.

|

| View of Skye from the summit of the Saddle, Glen Shiel |

Preparations: logistics

Opportunities for re-supply are scarce in the NW Highlands, and I’ll most likely be limited to Shiel Bridge, Kinlochewe, Ullapool, and Kinlochbervie. Consequently I’ll have to carry up to a week’s worth of supplies with me at any given time.

Some CWT hikers organise supply boxes to be sent to post offices along the route, but I’m not sure I can be bothered with the hassle. Most of these remote post offices only have limited opening hours, and if I arrive at the designated location (say) five hours early, I’ll have to hang around for five hours, or possibly make camp at an inconvenient location. I’d far rather carry enough supplies and re-equip where I can.

You can’t send stove fuel through the post, anyway, so that’s something I’ll have to source in the field. By my calculations, my new efficient alcohol burner setup should enable me to eke 330ml of fuel out for at least eleven days, so it’s hardly a major concern.

I’m going to allow twenty-six days for the route, but may complete it in twenty — it depends on a variety of factors, mainly the weather, final adjustments to the route, and how my feet hold up to the rigours of the trail.

Final thoughts

I’m really looking forward to this trip. I haven’t felt this excited about going into the mountains for years — the last expedition that really inspired me this much was probably Norway 2010. The idea of living in the wild for a month, slowly making my way north until there is no more north to travel, is a compelling one. In many ways I’ve been building up to something like this for years now, and although there is of course no guarantee that I’ll actually complete the route, I think that’s part of the allure. For its length it is one of Britain’s toughest hikes, and after more than a decade of mountaineering experience in Britain and Europe, I know that I’m ready for it.

I won’t be blogging on here during my journey, but I’ll be posting to Twitter when I can.

Maybe see you on the trail?

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.