Pilgrim’s Progress: a century of development in climbing equipment and technique

Alex Roddie charts a century of development in the tools we take for granted

This feature was first published in Mountain Pro Magazine, January 2016.

Take a look in your rucksack. If you’re a winter climber, you’ll find a pair of crampons in there, and two ice axes with bendy shafts and ergonomic grips. Combined with protective gear, these items form part of an elaborate system designed to make modern winter climbing possible. But it wasn’t always like this.

A century ago, people were climbing ice and mixed routes all over the UK and the Alps. Standards were not as high as they are today, but many of these climbers were operating at the cutting edge of their age. How did they do it? What was it like? And can we learn anything from the equipment and techniques of the past?

Nailed boots

Crampons have been around since the earliest days of mountaineering, but their popularity declined in the 19th century and did not recover for over a hundred years. Winter climbing first emerged as a distinct activity in the 1880s and 1890s – and during that period almost all climbers wore nailed boots without crampons.

You may have seen a pair of nailed boots hanging from the ceiling in a mountain pub, but few climbers still active today will have actually climbed in them. They evolved from the older hobnailed boots that had been used for thousands of years by anyone who needed a little more security on steep or uncertain ground.

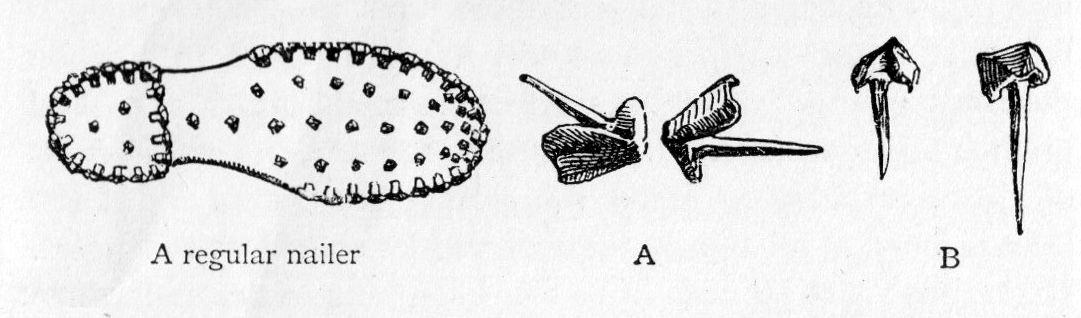

Over the years, two main types of climbing-specific boot nails developed from the humble hobnail. Clinker nails had a square profile that provided decent grip on rock and snow. The cobbler would hammer the sharp tine directly through the edge of the leather sole, then bend it back on itself; another flap of metal, integral to the nail, protected the end of the tine. This system was highly durable but it was impossible to replace nails once they had worn out. The Tricouni, a 20th-century innovation, aimed to solve that problem. With a hardened, serrated edge and two individual staples to fix each nail in place, they were more durable than clinkers and greatly increased security on small or icy holds.1

As for nailing patterns, the Badminton Library: Mountaineering (C.T. Dent et al, 1892) made this recommendation:

…with a row round the edge a climber can go anywhere in perfect safety, but it is better to add others shown in the drawing. The heel of the boot should be similarly garnished, a row of nails (often omitted) extending across the front part.

In 1963, Gaston Rebuffat’s On Snow and Rock hammered the final nail into the coffin, so to speak:

Nailing has been abandoned to good purpose in favour of Vibram soles … On rock their hold is incontestable; on snow, they hold as well as Tricounis; on ice, Tricounis are preferable, but, if the ice is really hard it is in any case necessary to put on crampons.

Both types of nail damaged the rock, in much the same way that crampons can cause damage when climbing in thin conditions. The difference is that nails were used summer and winter – and as the popularity of climbing increased, so did the erosion.

Eventually, nailed boots were supplanted by better technology. They were versatile in their day, but the combination of Vibram soles and crampons put an end to the era of the nailed boot.

The long ice axe

When faced with hard snow or ice, nailed boots alone were almost useless. The climber needed some way of cutting steps.

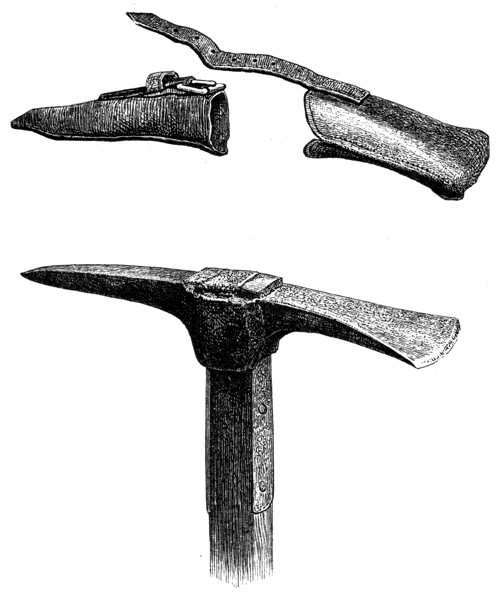

The ice axe evolved from the traveller’s alpenstock in the early 19th century. Early variants were up to five feet long, with a combined pick and hatchet blade at one end and a spike at the other. A separate short hatchet was sometimes used for climbing the steepest slopes. In the 1860s, Edward Whymper turned the axe blade 90 degrees to form an adze, and the modern ice axe was born2. The new design made cutting steps downhill far more practical and this increased the safety margin for early alpinists; before this innovation, it was often necessary to descend a mountain by the same route it had been climbed. Axes gradually became shorter too, a trend that continued for many decades.

I asked John Burns, a climber and mountain historian who has been active for many years, for his views on long ice axes.3

A friend of mine carries an 85cm ice axe. Once we came across a party who were trapped on a Scottish peak in a blizzard. They had no crampons, and they’d climbed up an ice slope before falling when attempting to descend. The only solution was to cut steps down several hundred feet of ice – made much easier by my friend’s enormous axe.

However, he adds:

Mountaineering is considerably safer now due to advances in equipment. Everything is much lighter, enabling climbers to move faster and reduce risk.

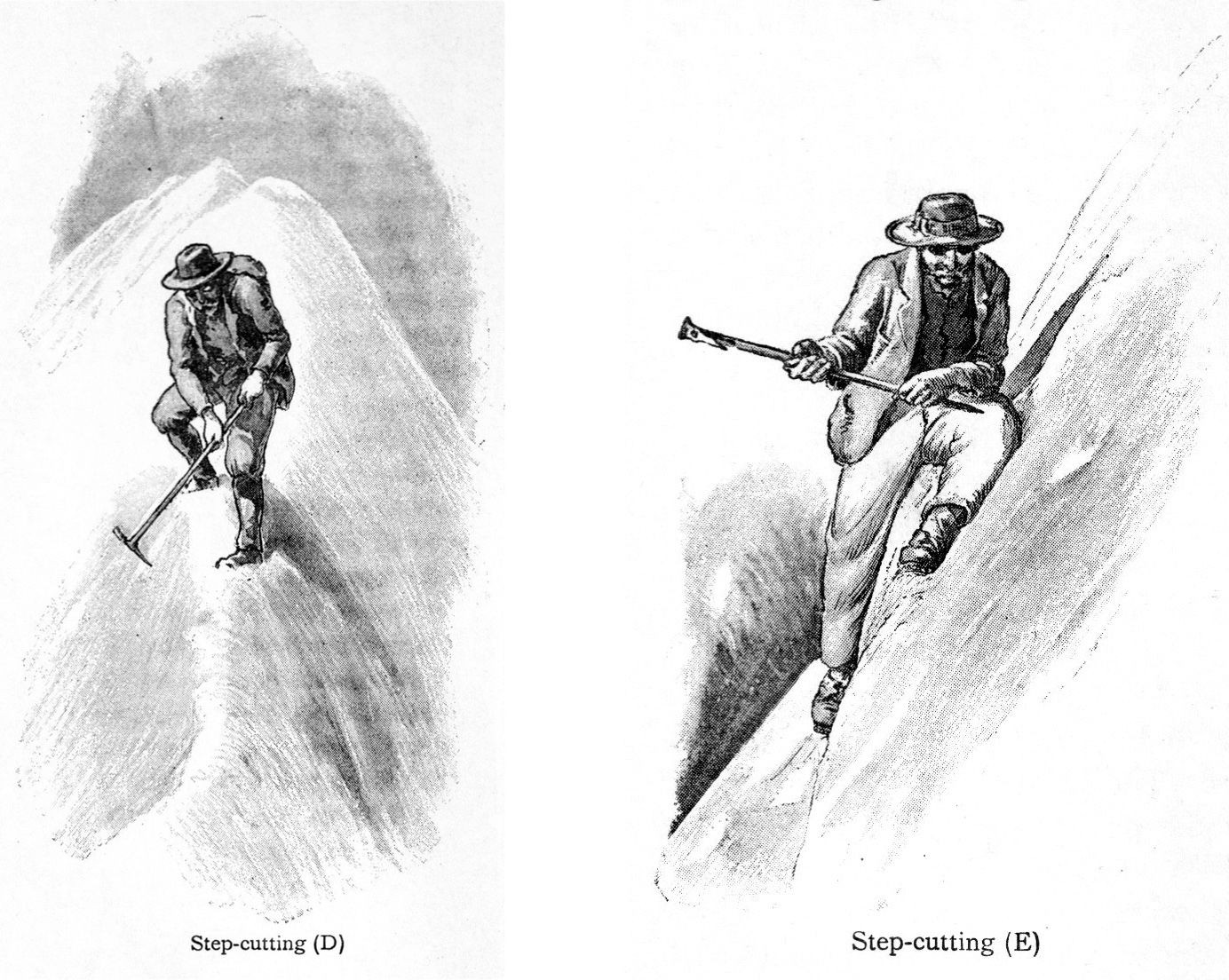

Cutting steps is a precise art. The climbing manuals of the past include whole chapters on the technique, and there are more ways of cutting steps than you might think – uphill, downhill, across the slope, with the pick, or with the adze – each requiring different skills that had to be practised.

It worked well enough for general mountaineering, but the traditional axe was not the best tool for the steepest climbs. In 1904, Harold Raeburn made the first ascent of Green Gully (IV,3) on Ben Nevis4. He was up against the limits of what was possible with his equipment:

To hang on with one hand, while that long two-handed weapon, the modern ice axe, is wielded in the other, is calculated to produce severe cramps in course of time … I suggest for climbs such as this our going back to … the light tomahawk-like hatchet stuck in the belt when not in use.

In the late 1960s, the ice axe evolved a curved pick. When coupled with twelve-point crampons, this enabled the front-pointing technique, allowing ice to be climbed directly, without the need to cut steps. The old methods were consigned to the history books and climbing standards improved rapidly.

Putting the theory into practice

There’s only so much you can learn from theory. I wanted to try it for myself, so I put together my very own Victorian mountaineering kit.

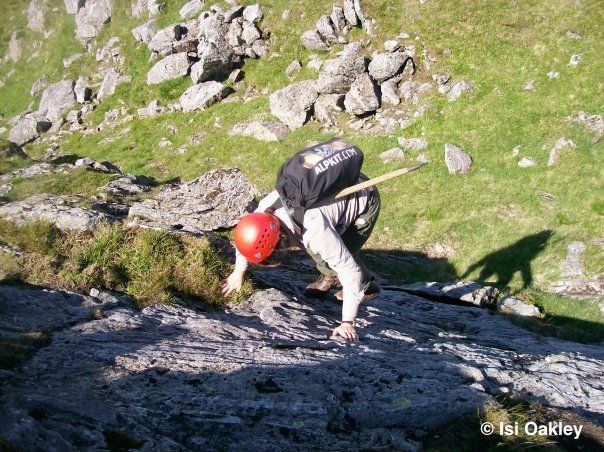

Sourcing Tricounis proved difficult. After finding an unused set on eBay I fitted them to a pair of traditional leather boots with the aid of a hammer and cobbler’s last. The ice axe required a bit more DIY; I rescued the pick from a rotting 1930s Aschenbrenner and made the shaft myself from seasoned hickory. A traditional tweed jacket, puttees and Dachstein mitts completed the picture. I was all set for some historical re-enactment in the Scottish mountains.

My friend Isi Oakley, an outdoor instructor, accompanied me on a summer ascent of Pinnacle Ridge (Mod), Garbh Bheinn. Although an easy route, I found it far more challenging than expected. In Isi’s words:

It was very educational and made me realise just what climbing grades originally meant – Difficult really meant it! Nailed boots on slabby gneiss led to Bambi-on-ice moments, and Alex often sought out the ‘winter line’ (grass and turf, rather than rock).

This highlights an important point – the pioneers often had to cope with far dirtier and more vegetated rock than we usually find today, and nailed boots can be useful on this terrain. But I struggled on smooth rock, and it’s easy to see why most climbers switched to Vibram soles when they became available.

Winter climbing was completely different. I found the combination of nailed boots and long axe surprisingly effective for routes such as Dorsal Arête (II), Central Gully (I/II, Bidean nam Bian) and Wandering Wombat (I/II, Stob Coire nan Lochan). These climbs are trivial by modern standards but were perfect for practising the old step-cutting techniques, and I even found that bludgeoning through a cornice was much easier with a long axe. The tweed jacket wasn’t bad, either – as good as modern softshell below freezing, but soggy and uncomfortable in the rain.

I spoke to John Porter, author of One Day as a Tiger: Alex MacIntyre and the birth of fast and light alpinism5 and an expert in climbing history. He had some insights on how things have changed, and helped me to understand the bigger picture. It’s about far more than just nailed boots or crampons, long axe or short.

Long axes are still an advantage on non-technical terrain and Grade I-II winter routes, but the art of suffering for long periods in extreme conditions is now restricted to Himalayan winter climbing. From a time when climbing ice was terrifying, terrifying routes can now be climbed in relative comfort due to the improvements. Cutting steps, frozen feet and placing corkscrew ice wires while balancing on insecure ten-point crampons now seem stupid but it is how routes like Point Five Gully (V,5) and Zero Gully (V,4) were first climbed.

Safety, comfort, and standards have all improved. But have we lost anything? John Porter said ‘climbing is much more a sport than a way of life these days – not a criticism, just evolution through technical improvement’. And Isi, despite being sceptical of my nailed boots, said ‘step-cutting is a bit of an art. I also wonder if most of us who climb are not as hard as those a century ago. We have our modern comforts and use them – I wonder if we could hack it without!’

I’m not the only one to have tried out what it’s like to climb with the equipment of the late 19th or early 20th century. In July 2015, Hugo and Ross Turner set out to climb Mt Elbrus (5,642m). One of the twins wore modern kit, while the other wore a replica of the suit George Mallory wore on Everest in 1924: leather boots, tweed, wool, and Gabardine6. In 2006, Graham Hoyland climbed on Everest with a similar set of replica equipment and concluded that the gear was sufficient even above 8,000m – but only as long as the climber kept moving.7

My own experiment made me realise that climbing ability isn’t about gear. Nowadays most of us use equipment designed for higher grades than we can climb. It’s possible to climb easier routes with extremely basic gear, given the right skills, and I don’t think it’s too much of a stretch to say that gear manufacturers could learn from the equipment of the past. Is there still a market for a long cornice-busting ice axe, or footwear inspired by nailed boots for slimy or verglassed mixed climbing? New innovations come all the time, but the game of climbing remains the same: get to the top, get down safely, and have some fun along the way.

- http://www.outdoorgearcoach.co.uk/tricouni-nails/ ↩

- Scrambles Amongst the Alps, Edward Whymper, 1871 ↩

- This story and more can be read in John’s thrilling new book, The Last Hillwalker ↩

- Ben Nevis: Britain’s Highest Mountain, Ken Crockett, 2009 ↩

- https://www.v-publishing.co.uk/books/categories/biographies/one-day-as-a-tiger-paperback.html ↩

- For a report on how the climb went and how the equipment performed, read this article on the Berghaus blog: http://community.berghaus.com/gear/how-has-mountaineering-clothing-evolved-over-the-past-100-years/ ↩

- There’s more on this subject in the June 2017 issue of The Great Outdoors Magazine. ↩

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Subscribe here to receive my occasional personal newsletter in your inbox. (For the fun stuff, please consider subscribing to Alpenglow Journal instead!)