Ian Roddie, 1938-2018

In memory of my dad, who introduced me to the good things in life

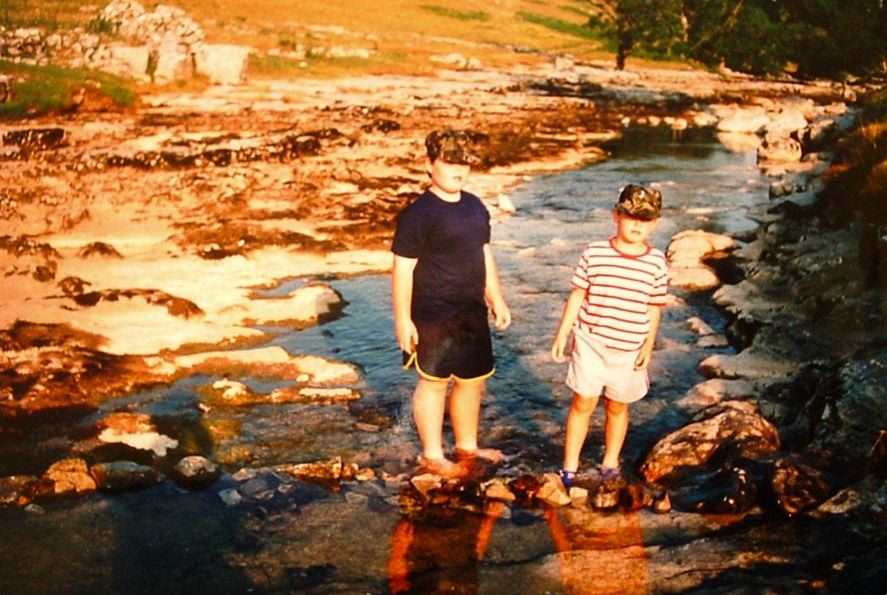

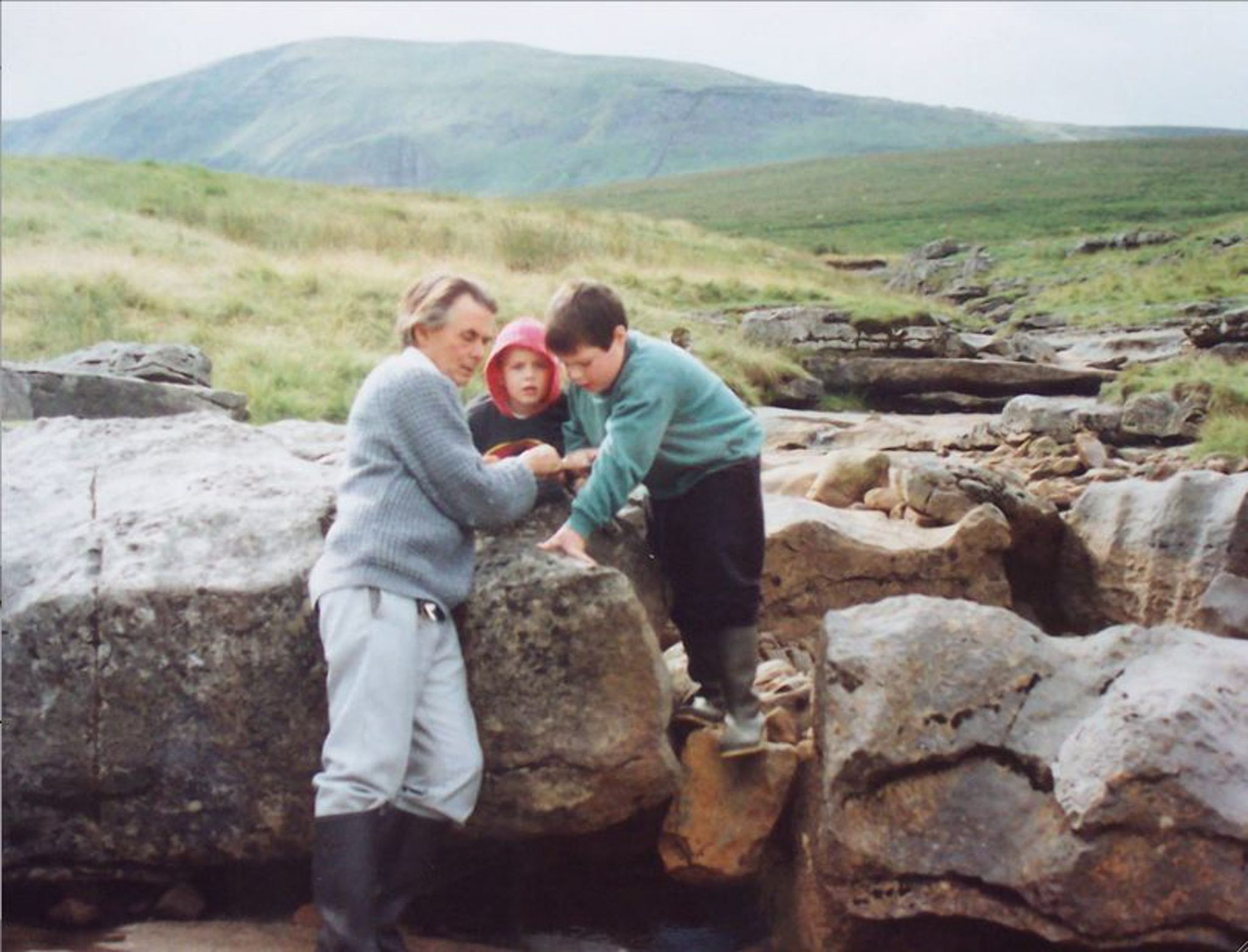

On the 5th of August 2003, my brother James and I went for a hillwalk with our dad and our crazy golden retriever Amber.

The objective of the walk was simple: we wanted to explore the old mining valley in the Coniston fells above Tilberthwaite in the Lake District. For the previous week or so we’d been spending time as a family (minus Mum, who was at home looking after Granny), camping, revisiting old haunts from our childhoods, tramping the hills, living the good outdoor life. But for reasons that did not become clear to me for some years, the Tilberthwaite walk was destined to shine like a beacon in my memory.

It started with a brutally steep ascent that left me panting – I wasn’t especially fit then – and Amber looking wilted, tail between her legs. It was a hot August morning and the fells had begun their slow and subtle turn from the bland greens of July to the mottled duns, yellows and deep emeralds of early autumn. Even then, my mind was echoing back to the particularly vivid autumn of 1997, when we spent a few days in Skelwith Bridge watching the larch forests turn copper and gold. It was much too early for that colour show, sadly.

Soon we came upon the abandoned mine workings, and my overactive teenage imagination went into overdrive. To understand why, a little context: as a child I’d been obsessed with fossils, minerals, and the novels of Arthur Ransome, particularly Pigeon Post in which the youthful protagonists believe they’ve found gold in the Coniston fells. These passions were shared with (and encouraged by) my dad, who had spent the happier part of his own childhood roaming the Yorkshire Dales looking for minerals and having adventures.

We delved into mossy abandoned levels, and I scraped about in the rubble for overlooked gemstones. In one hole I convinced myself I’d found silver ore, and Dad indulged me, even though it was probably just copper – same as the ‘gold’ discovered by the children in Pigeon Post. Before heading back down to the car, we had to cross the beck and a scene is etched into my memory of poor Amber taking her time summoning up the courage to leap over the torrent. When she jumped, onlooking hillwalkers cheered.

For that brief, golden walking holiday, I forgot my A-Levels and the imminent pressures of young adulthood, and was able to be a child again for one last time. It was a perfect coda to a childhood spent looking forward to family holidays in the Dales and the Lakes, in which our dad passed on his love of hillwalking, nature, mucking about in boats, and the simple pleasure of reading a good book somewhere quiet.

But that trip was also an important beginning. It rebooted my love of the Lake District and laid a concrete foundation for the person I am today. If our dad had not taken us on that trip, there’s every chance that James and I might never have dived headlong into the world of mountains and adventure. Our dad gave us a priceless and timeless gift that summer.

The last 541 days

When Dad fell ill in summer 2016, I knew instinctively that something was wrong, and came home early from my Pyrenean backpacking trip because intuition told me I was needed. Within a few weeks he had been diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma.

For more about those dark days, read my essay The most important thing.

In the months that followed, Dad came a hair’s breadth from succumbing to the cancer, but once he began to rally there seemed no stopping him. Chemo seemed no hardship at all. Never once did he complain or bemoan what had happened (although he suffered terrifying nightmares at times in hospital). He withstood pain, discomfort and indignities with great patience, and when he spoke of events on Ward 7a it was usually to tell us how kind a nurse or his consultant had been. Meanwhile, he continued to write in his diary, which contains a daily record stretching back to 1985. There are only a few gaps in this mammoth chronicle; most date from his darkest days in late 2016 when he was incoherent and fading.

On the 12th of April 2017, he was declared free of cancer. For a few months he was fit and healthy. His strength (and hair) returned. My parents moved house to be nearer to me. Those few months were a precious gift.

By the 20th of September, the lymphoma was back, and this time it did not let go.

I won’t dwell on those final few months – months that were at once bitter and beautiful, full of a hundred sorrows and unexpected blessings. I won’t dwell on how I again instinctively knew to cancel my planned trip to Scotland on the week of his death, even though he seemed basically fine when I took the decision. Instead, I’ll try to paint a picture of the man how he was.

The gift of impermanent permanence

Our parents had children comparatively late in life. Dad was already 47 in 1986 when I was born. In the 1970s he designed and built a yacht – by hand, and from scratch – in a shed on the Suffolk coast, and kept Yorrel on the River Deben for many years. His tales of life on board are the stuff of my childhood’s dreams and legends. He would enthrall me and James with stories of gales on the river, of peculiar lightning storms, of what he believed to be a Russian spy chased out to a waiting submarine in the North Sea. He also told us of the perfect calm, solitude and focus of a golden morning on the water without the chatter of radio or TV to disturb his reading and writing.

Most of his artwork is from that era. The simple oil paintings depict life on the river, or scenes from the Yorkshire Dales where he had grown up. His paintings are not masterpieces, but there is an honest and human beauty about them.

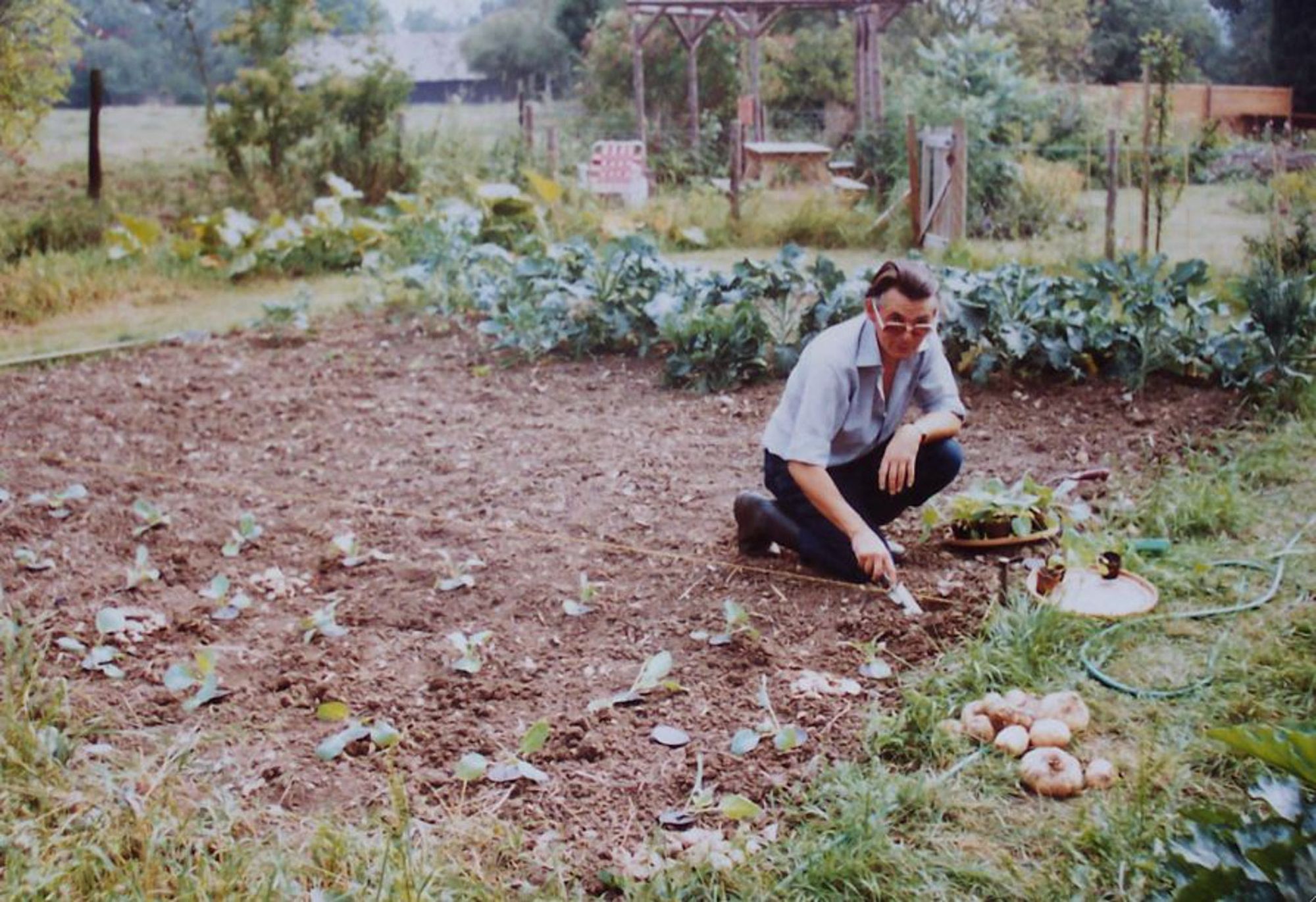

At work, Ian Roddie was a building inspector. His work was all blueprints and building regulations. He took early retirement when I was still very young, which was a good move: he was around a lot, and some of my happiest childhood memories involve me and James playing in the garden while Dad dug for vegetables or sat in the sun carving a walking stick. Although he could be suitably stern if we needed telling off, I remember him as a calm, happy and composed presence with an admirable ability to focus 100 per cent on what he was doing. That sense of calm extended throughout his life and could be seen right up until the end.

He taught me to read before I started school, and is responsible for my love of literature to this day. There are many correlations between our lists of favourite books: the Foundation Trilogy, Swallows and Amazons, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and 1984 to name but a few. He encouraged my interest in writing and, much later, my published fiction encouraged his own literary efforts, and he died with several unpublished novels to his name. Our taste in music is similar too: Mozart, Beethoven, Bach, Stravinsky. All the good, timeless stuff.

In everything he did and liked, my dad valued things that were proven, substantial, of lifelong value. He was wary of fads and phases, of ephemeral things, of products with built-in planned obsolescence. These values are at the core of my own soul.

A final gift

In 1969, he purchased a new camera, the Olympus Trip 35, mostly for his mother to use because it was simple. My granny used it for years and there are slides in Dad’s Kodachrome collection showing her holding the camera in the early 1980s. Later, it found its way back to him, and on family holidays my brother and I were allowed to use the Olympus Trip – again, because it was simple. I have vivid memories of Dad showing me how to set the focus with the distance scale. In 2000, I took the camera to Flanders on a school trip, and remember thinking at the time it was pretty cool that such an old camera was still working and useful.

In 2014, Dad gave the camera to me. I still have it. It still works. I still shoot with it regularly, and it still creates beautifully crisp and detailed images – with modern scanning techniques, the Olympus Trip 35 can create 30MP digital files.

It will take us years to read every page of his 1985-2018 diary, which ended with a hurried handwritten entry made only four days before he diedI take the time to tell you this because I feel it perfectly expresses my dad’s character. He was a man who knew what was important in life, who understood the value of things; a man who was happy with what he had and never sacrificed that happiness in the chase for wealth, success or power. His wisdom was quiet, calm, modest and honourable. That we have lost him so soon is a bottomless tragedy. I am grateful for many things but sad beyond measure for the conversations we’ll never have.

Last week, I wrote to a friend that my dad’s final gift was to show us how to face mortality with grace, acceptance and dignity. However, he left us one more gift.

On his laptop we found 30GB of photos and writings. Together with his paintings and massive collection of Kodachromes and Ektachromes dating back to the 1950s, this constitutes his entire life’s work. It will take us years to read every page of his 1985-2018 diary, which ended with a hurried handwritten entry made only four days before he died. It may take me even longer to read his enormous collection of unpublished fiction with the critical objectivity it deserves.

But in one fact I take great comfort: with every one of his photographs I see for the first time, with every one of his stories I read, I’ll get to know him a little better. Maybe our conversations aren’t over yet after all.

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Subscribe here to receive my occasional personal newsletter in your inbox. (For the fun stuff, please consider subscribing to Alpenglow Journal instead!)