The Alder Trail

Alex Roddie answers the call of Ben Alder’s wildness in this ambitious long-distance trail between Fort William and Aviemore.

This feature was first published in Trail magazine, November 2016.

* * *

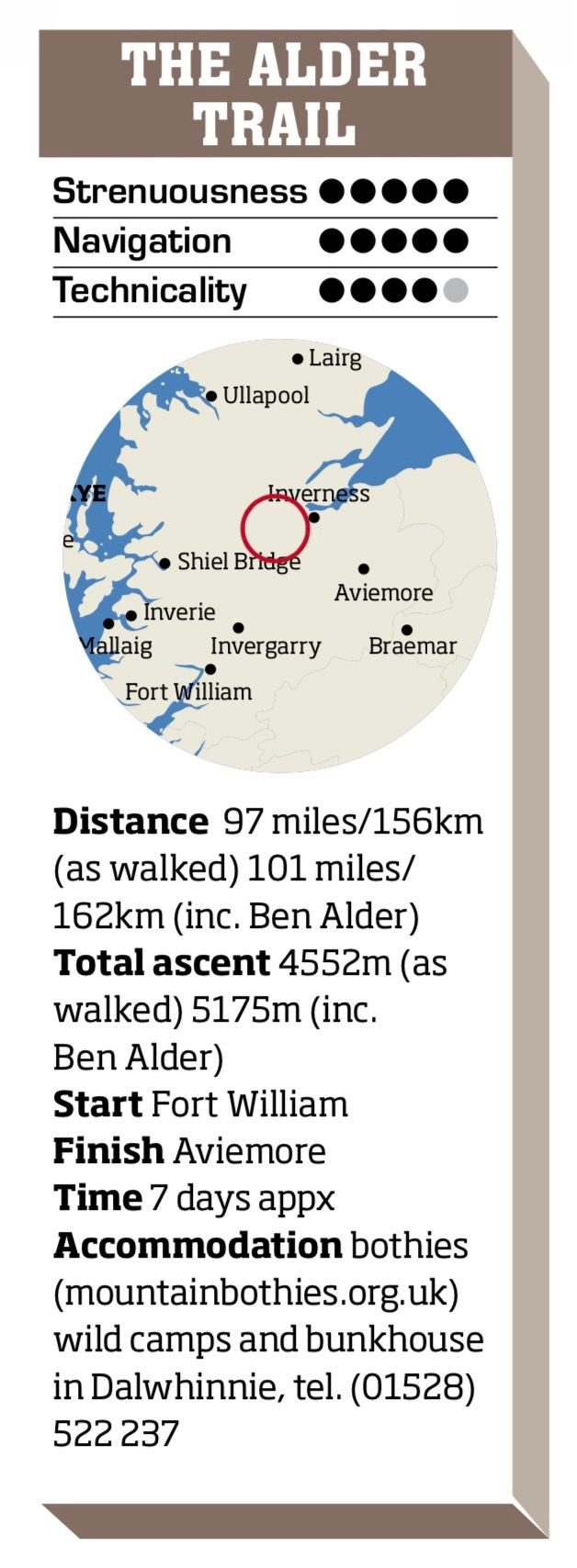

Scotland is home to some of Britain’s best long-distance trails: the popular West Highland Way; the Cape Wrath Trail, picking its way 200 miles through the wilderness of the north-west Highlands; the otherworldly Skye Trail… often, the names alone will get your boots twitching. But what about the East Highland Way, between Fort William and Aviemore? There, some of the best mountain landscapes in the UK await the adventurous walker eager to take in a summit or three – but the trail mainly sticks to tracks, paths and roads. So, we made up an alternative: the East Highland Way backpacking hillwalkers deserve. We’ve called it the Alder Trail.

Firstly, that name. Ben Alder has a certain mystique. It isn’t one of the highest Munros, but it is one of the more remote so any journey into the Alder Forest generates a frisson of excitement. It’s a place for the connoisseur of wild landscapes. You can bag it in a day if you’re really fit, or do most of the approach on a bike; but to make the most of it you need to spend a night or more out there. I plotted several route alternatives, but kept coming back to Ben Alder’s wildness, its irresistible challenge. This trail came to be defined by Ben Alder itself – both on the map and on foot – but it isn’t the only barrier to overcome before you finally reach Aviemore.

Let’s look at the route. It’s 101 miles, similar to the West Highland Way, but it’ll take longer (I planned for seven days). Strong legs? It has over 5,000m ascent. Confident in your compass work? Pathless stretches will test your skills. You’ll be immersed in an unforgiving landscape often far from the honeypots, where you’ll need to be self-sufficient for several days at a time – with no chance of a comfy hotel. If you’re currently thinking that sounds brilliant… the Alder Trail is for you.

* * *

I nodded hello to the other walkers clambering along the rocky path to the spectacular An Steall waterfall from upper Glen Nevis. It was late April, that exciting time of year when the hills can’t quite decide whether to cling onto winter or power through to summer, so I’d packed a wide range of kit from sunglasses to ice axe. But this was a long-distance hill walk, so I’d also done my best to pack light. On my feet were trail-running shoes – my tried-and-true favourites for long walks – and a few booted hikers gave me funny looks as I passed. “Ice axe and trainers, mate? You’re having a laugh,” one chuckled.

There were fewer people beyond the 100m cascade of An Steall, and within the hour I found myself navigating by compass through a bog. The clag had come down, cloaking the mountain ranges beside me and Ben Nevis behind, and with it came the first of many snow showers. I put on my woolly hat and placed my faith in the forecast of better weather to come.

The previous year, on the Cape Wrath Trail, rivers swollen by snowmelt had stopped me in my tracks. I expected the same challenges in upper Glen Nevis, but found the rivers low – no doubt thanks to the chilly weather slowing the thaw. I splashed across a tributary, my feet already wet from the bogs. Meanwhile, cloud and sunshine chased each other around the mountains, and I sat on a rock for a while to watch the showers dash themselves against the snowline of the Grey Corries.

I didn’t need a bothy pitstop after a gentle first day, but when I saw Staoineag perched on its perfect little knoll above the river I couldn’t resist. It’s a small building, in use as recently as the early 20th century as a family home, and I tried to imagine what it must have been like to live in this wild location throughout the year. While I gathered wood and made preparations for a fire, the sky clouded over again. Soon snow was howling through the glen.

The next morning, seeing the bright glow of fresh snowfall through my eyelids before I even opened them, I lay still, feeling reluctant to get up and face the trail. When I did, I looked out the window at a landscape returned to winter. I had 25km and two Munros ahead of me. Today’s going to be tough, I thought.

I knew I had been lucky the previous day on Carn Dearg and Sgor Gaibhre. I had no intention of being unlucky on Ben AlderAnd it was. I left Glen Nevis and entered the Alder Forest, a paste of wet snow coating everything. A hard wind blew spindrift into my face and layers of dull white hid the landscape. I put my fleece and gloves on against the chill, and started to worry about the Munros I planned to cross on my way to Ben Alder Cottage. Should I take my foul-weather alternative? The question gnawed at me as I trudged towards the Loch Ossian hostel, where I would have to make my choice. The two Munros ahead of me that day were Carn Dearg (941m) and Sgor Gaibhre (955m): easy climbs, but, as every walker knows, the gentlest hill can feel like the north face of the Eiger if the weather is bad enough.

Then I thought about my alternative route. I pictured myself stumbling through semi-frozen peat bogs, maybe breaking through and sinking up to my waist. The thought made me shiver, and I resolved to go over the Munros.

Halfway up Carn Dearg, face rasped raw by spindrift, I almost turned back. I couldn’t see a damned thing; snow goggles hadn’t made it into my lightweight pack. However, with the help of Microspikes – traction devices of chained stainless steel spikes – and waterproof socks, my trail shoes were holding their own, just. The drifts were getting deeper and I navigated by compass bearing, always keeping an eye on the GPS. Winter mountaineering is all about continuous assessment of hazards and I knew I was pushing things.

The bealach between the two Munros tested me to my limit. Ferocious gusts bowled me off my feet and the dotted trail on my iced-up GPS display showed a crazy zigzag as I fought the storm. With ice axe in hand, I negotiated broken rocky ground, steep hard snow, and thigh-deep drifts in zero visibility, unable to feel my hands or face.

By the time I reached Ben Alder Cottage, the bothy on the shores of Loch Ericht, I felt as if I’d spent the day being beaten up by grizzly bears. I’d been walking on autopilot for the last hour, although at times I had raised my eyes to the bulk of Ben Alder above and wondered if I’d be heading up there the next day. A couple staying at the bothy managed to revive me with fire, whisky and storytelling. They thought I was nuts, and told me so at some length. Maybe I was.

Climbing Ben Alder was meant to be the climax of the Alder Trail, but when I woke the next morning and saw even more fresh snow on the ground outside the bothy, I made the immediate decision to stay in the glens. I knew I had been lucky the previous day on Carn Dearg and Sgor Gaibhre. I had no intention of being unlucky on Ben Alder.

As I plodded mile by mile along the easy trail that follows the shore of Loch Ericht to Dalwhinnie, I felt like I’d cheated. There’s no rulebook for long-distance walking – walk your own walk, they say – but I had avoided this trail’s raison d’être, and the proof loomed beside me. I hoped that the crossing of the Cairngorms would make up for it.

Dalwhinnie’s roughly the halfway point, and after three days and 48 miles it made a good place to take stock and think about the challenges ahead. I had sent a food package to the bunkhouse – the only point on the Alder Trail where resupply is possible – and I tore open the box in the adjacent cafe, marvelling at the treasures I now possessed: Snickers bars! Raisins and peanuts! Dehydrated spaghetti bolognese! Instant coffee! I feasted on surplus rations that night, but later, sitting on my bunk amid piles of drying gear, I studied my maps and realised I had a lot of high ground still to cross – and all that fresh snow wasn’t going anywhere. It would be tough, it would be cold, and I’d be pushing my margin for error by climbing Munros in winter with little more than trainers

on my feet. You could give up, you know, a voice whispered in my head. There’s a railway station just down the road.

Then my resolve hardened. The whole point of this trail was for it to be a challenge. I liked cold and tough, and I had confidence in my skills and gear. If I’d wanted an easy stroll, I’d have done the East Highland Way.

Dalwhinnie to Glen Feshie was a great stage. Carn na Caim (941m) is a straightforward mountain, made a little more interesting by the huge quantities of fresh snow, but at least I had some views. It was like a mini version of the Cairngorm plateau up there. A skier whizzed past me, making it all seem so easy while I post-holed, squinting into the mid-day sun. I felt like I’d deserved this little slice of good weather.

* * *

I reached Glen Feshie on day five, after 75 miles on the trail. It marked the beginning of the end, but I was starting to adjust to the rhythm of life on foot and didn’t want to stop. Ahead of me, the Cairngorms formed a high natural barrier: by far the most serious stage of the trip. I had to get across and through them to reach Aviemore, and this time there could be no diverting through the glens. It was up and over, or quit and go home.

I ended up camping in Glen Feshie for two nights, waiting for the wind and rain to stop. This was no great hardship – it’s a wonderful place, full of beautiful regenerating woodland and natural water courses – although discovering I’d camped on a tick nest made things a little more exciting on the second afternoon.

To my left, icefields lingered in the vast amphitheatres of Braeriach, where the snow rarely melts, even in the height of summerI climbed the west slopes of Carn Ban Mor (1052m) and hit the snowline by mid morning. Soon I found myself right in the middle of the Moine Mhor: a vast, featureless snowy plateau. Here the true challenge of the Alder Trail made itself felt. On the East Highland Way you follow good paths at low altitude; here the line between backpacking and mountaineering is blurred. While low cloud cleared from the summits all around me, I watched every twitch of my compass needle and scrutinised the contours of my map, trying to figure out if I was far enough west to avoid the river hidden beneath the thawing snowpack. Then – whomp – my leg crashed through and I could see fast-flowing water a metre below. I hauled myself out, heart racing, and kicked steps to higher ground.

Finally I began the descent of Glen Geusachan – a wonderfully wild, remote place where a meltwater torrent thundered down from the crags of Braeriach and Cairn Toul, cutting through a pathless swathe of wild land and pointing the way ahead to the Corrour Bothy. Glen Geusachan is a superb section for walkers who love a slice of wildness with their backpacking. I stood for a while on a rock at the edge of the cliff, watching cloud shadows move over the bright snow, and I felt how lucky I was to be there.

Corrour bothy is the best halting place for the final night on the trail. The huge pass of the Lairig Ghru cuts north-south through the Cairngorms and provides a straightforward escape to Aviemore – but it is by no means easy. During my final climb up to the pass I fought against a gale blowing straight into my face, and I must have burned five times as many calories as I would have done in a flat calm. To my left, icefields lingered in the vast amphitheatres of Braeriach, where the snow rarely melts, even in the height of summer.

I reached Aviemore after eight days and 97 miles of hard walking. When I bumped into an East Highland Way walker in town, we talked about our adventures, and I told him I’d also come from Fort William – the hard way. He gave me a puzzled look and said “Don’t you know there’s an easy route through the glens?”

* * *

The Alder Trail is a route for the backpacker who wants more. If you’re ready to move on from well-trodden paths, and dream of a wilder landscape where you have to make your own way and rely on real mountaineering skills, then this is the challenge you’re looking for. Or maybe just pick up a map and plot a route of your own from A to B, taking in as many contours and high places as you possibly can. You’ll no doubt discover places that otherwise might have gone entirely unnoticed, with enough time to really get to know the landscape. I can’t think of a better way to enjoy the mountains.

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Subscribe here to receive my occasional personal newsletter in your inbox. (For the fun stuff, please consider subscribing to Alpenglow Journal instead!)