Haute Route Pyrenees planning: maps, apps, GPX data, and more

Updated 2019-07-12 to reflect my final setup on the eve of my hike.

From mid-July 2019, I’ll be thru-hiking the Haute Route Pyrenees. Planning is now well underway, and in this blog post I’d like to outline my approach to maps, route planning, and how I’ll handle navigation on the trail.

For background on my hike, check out this post.

When it comes to planning, there are two kinds of backpackers: those who like to keep things fluid and flexible, and those who prefer to plan their adventures beforehand. I’m in the latter category. Although planning out individual days makes little sense on a long route – there are so many variables that detailed plans inevitably fall apart – I do like to have a clear picture of all possible route variants, major landmarks, distances, and potential resupply points. I think this approach offers the best of both worlds.

It all starts with a guidebook and some GPX data.

Guidebook

I will be using a combination of guidebook info sources:

- The new edition of Cicerone’s guidebook to the Pyrenean Haute Route. The third edition has been extensively revised by Tom Martens. I will be carrying an electronic copy on my phone; my wife will have the paper copy to keep track of my location.

- The online guide at hrpguide.org. Peter Forrest has extensive knowledge of the HRP and has been involved with the two most recent editions of the Cicerone guide. His supplemental information looks like it will be very useful.

- Whiteburn’s Pocket HRP Guide. An alternative (and very concise) data source.

Although I’ve used these data sources to plan my trail, I don’t intend to stick to the recommended day stages in any of them, for two reasons:

- I plan to complete the route in a faster time than the 44 days recommended in the Cicerone guide.

- I will mostly be wild camping. The Cicerone guide assumes that the hiker will mostly be staying in huts or other accommodation.

GPX data

To help me plan my route itself (including the variants I’ll be taking and any alternative routes for bad weather), I have created a set of GPX files. GPX is a standardised format used by all GPS devices and mapping apps. Once a set of GPX data for a trip has been created, it can be loaded into any app and used interchangeably. This is very handy on the trail!

There are a lot of GPX files for the HRP floating about on the internet, but I am wary of directly using someone else’s GPX tracks for planning, because I might end up making the same mistakes that person did. Although I often use publicly available data sources as a starting point, I always create my own final GPX files. Here’s how I did it for this trip:

- I used the GPX files from hrpguide.org as a starting point. These files consist of 45 routes and 579 waypoints, but they do not offer continuous tracks; these are ‘join the dots’ routes from waypoint to waypoint, omitting detail in between. Some people prefer this kind of route, but I like detailed tracks.

- To create a set of tracks offering a more accurate picture of distance and elevation, and which I can use on my phone and smart watch, I went through my guidebook data and carefully drew my own tracks using the hrpguide.org routes as a rough guide. I used ViewRanger to create these tracks.

- I did this for both my planned main route and any possible variants. I also kept all of the original numbered waypoints from the hrpguide.org data.

- Using Garmin Basecamp, I split the resulting 738km track into five segments. This is important because the full track was too big to fit on my Suunto watch (it had too many track points).

- I exported the five tracks and 579 waypoints as a single GPX package that I could import into my navigation apps.

Smartphone apps

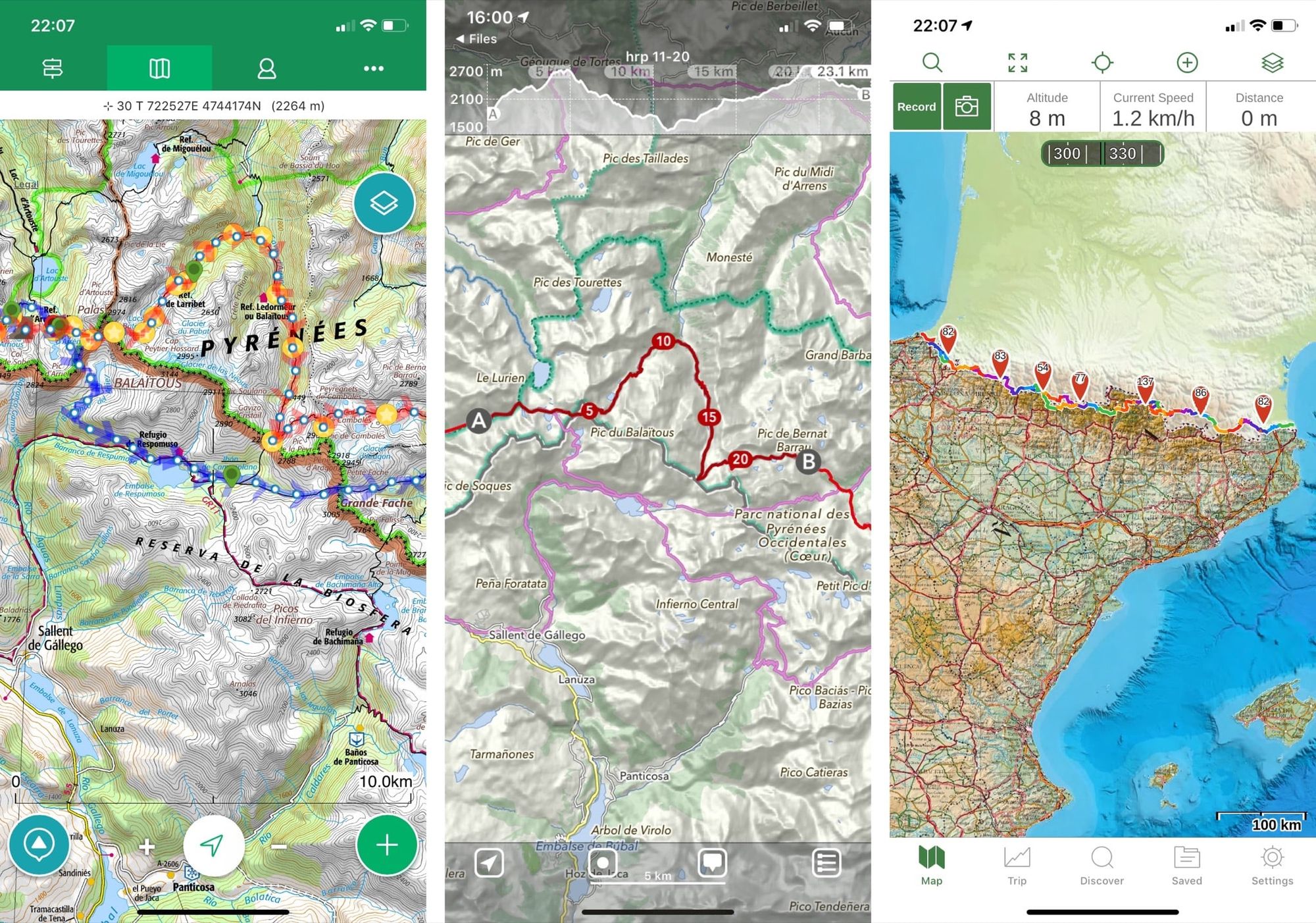

I will be using several different apps to give me different perspectives on my route:

- ViewRanger. Always the most important app on my phone; I anticipate using this to navigate most of the time. I have the Pyrenees map set covering both sides of the French/Spanish border.

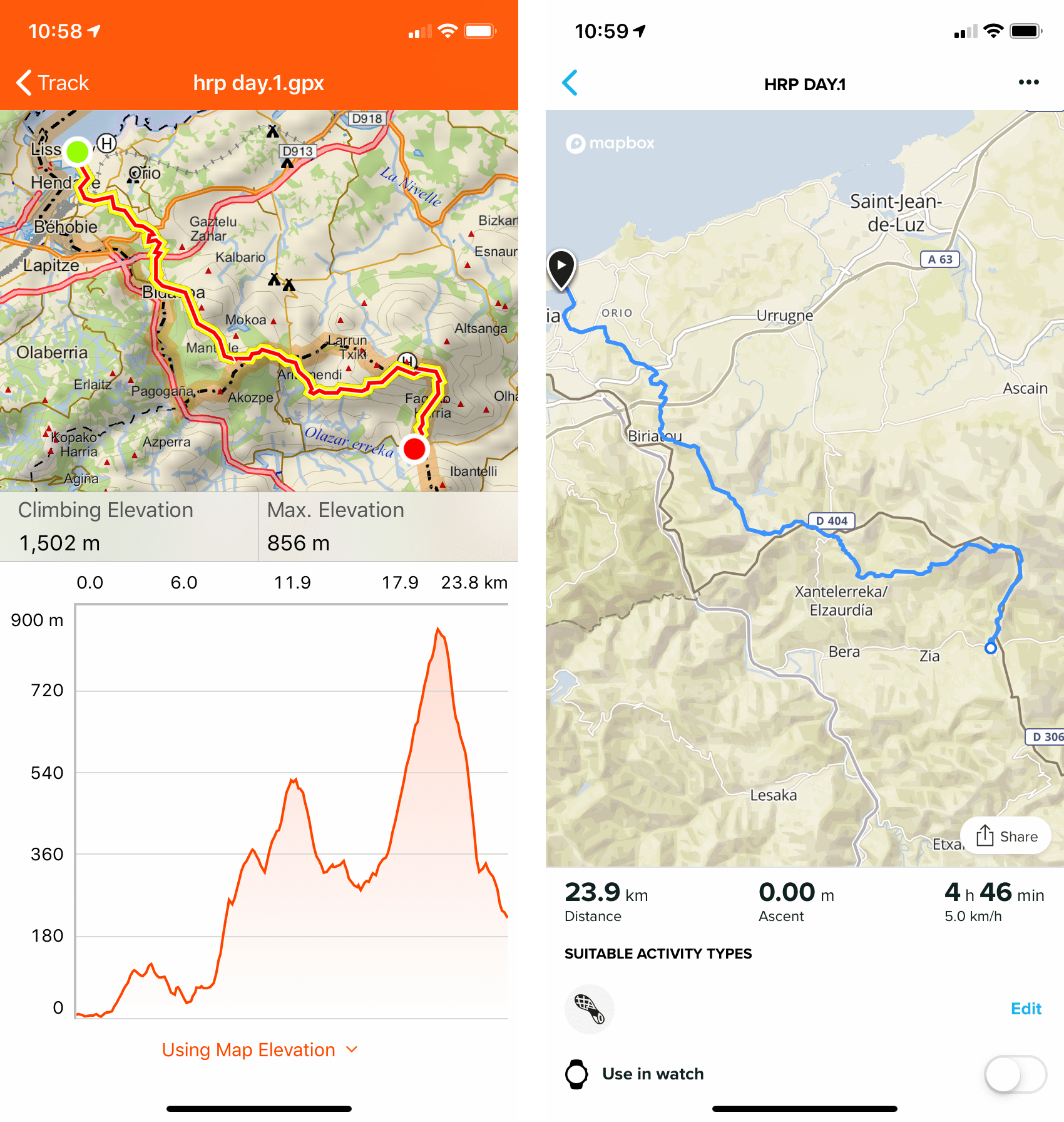

- Suunto. The Suunto app is used to transfer routes to my Suunto 9 Baro watch and to download recorded activities from the watch at the end of each day. This will allow me to analyse the day’s walk and save a GPX trace of where I’ve been. The watch can only store a few days of recorded activities so it’s important to be able to sync regularly to the app.

- MapOut. A simple but deceptively powerful app with OSM offline mapping. OSM mapping is less detailed but also less cluttered, making it great for getting a broader perspective. The map also has some nice features such as very easy-to-use distance scales and altitude graphs, plus a huge amount of data for established trails. Creating GPX files is very fluid in this app.

- Gaia GPS. I’ll mostly be using this app as a backup to ViewRanger, but it has a different way of viewing maps (with transparency-enabled layers) that could be useful from time to time.

I also experimented with the Garmin Explore app. This fairly new app is a mobile version of Basecamp for communicating with Garmin GPS handsets and watches. Although I don’t have a compatible device, the app has some nice features that make it worth a look for organising and visualising GPX files, and is better in many ways than Suunto’s companion app. Ultimately I decided not to keep it on my phone, as (for me) its functionality can be replicated almost exactly by MapOut.

Suunto watch

Due to some reliability problems, I have decided not to carry the Suunto. Ultimately, it’s a convenience – its functions can be replicated almost exactly by the Garmin eTrex that I plan to carry – so there is simply no point in having it if it won’t be reliable. I leave the information below for interest.

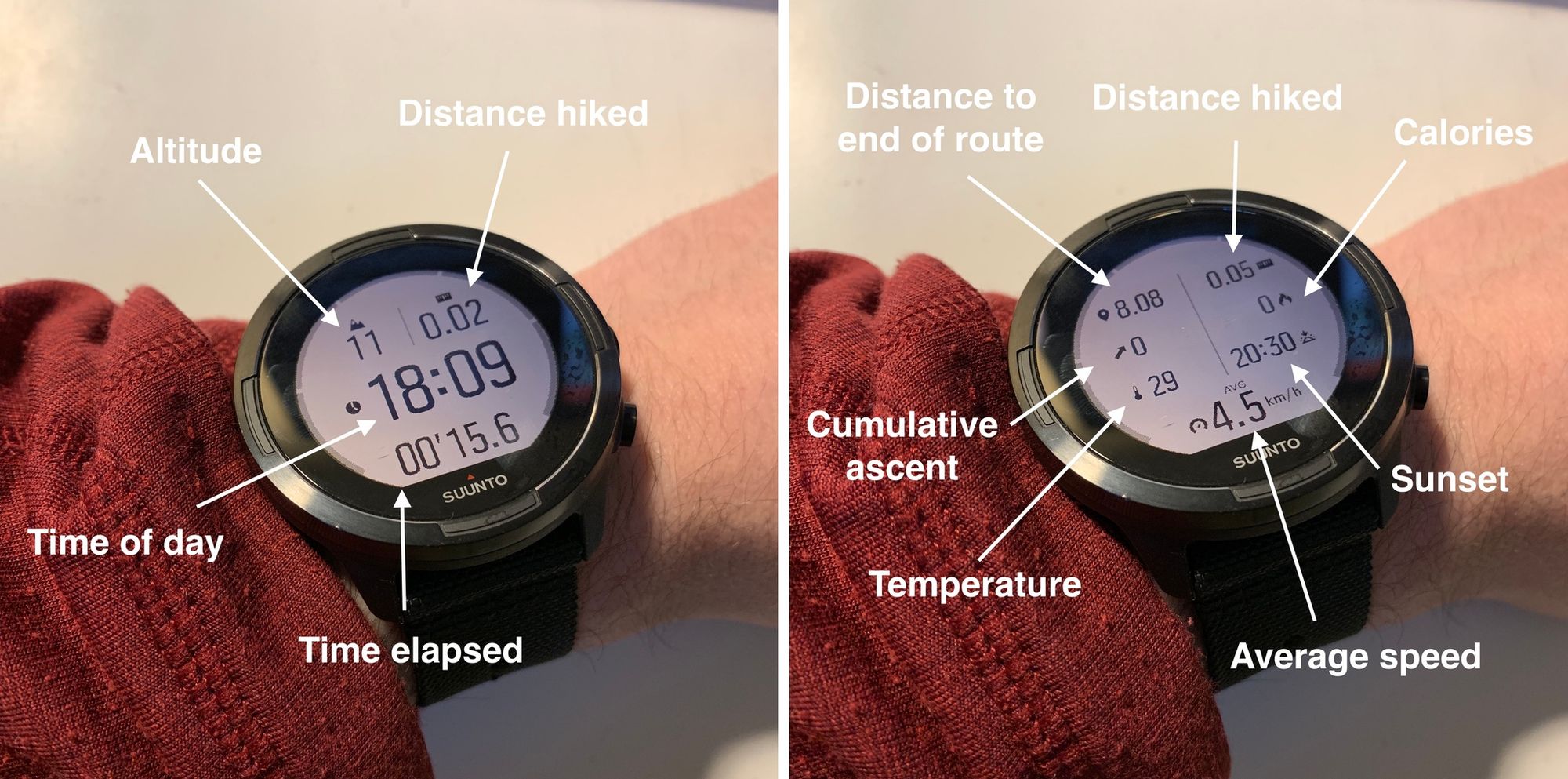

In my post about background and gear, I mentioned that I’d be using the Suunto 9 Baro smart watch. Here I’d like to go into a bit more detail about how I’ll be using it on the trail.

The Suunto will have my planned tracks for the whole trail stored in its memory. At the start of each day’s walk, I’ll begin recording an activity and set the watch to navigate with the appropriate track. I’ll mainly be using the watch for the stats and for recording GPX files, but the navigation screen will also be useful for quick direction checks.

Here are the custom screens I’ve added to the Suunto for use in activity tracking mode:

Screen 1:

- Altitude

- Distance

- Time of day

- Time elapsed

Screen 2:

- Distance to end of route

- Distance hiked

- Calories burned (approximate at best)

- Sunset time

- Average speed

- Temperature (influenced by body heat; only accurate after 10+ minutes off the wrist)

- Cumulative ascent

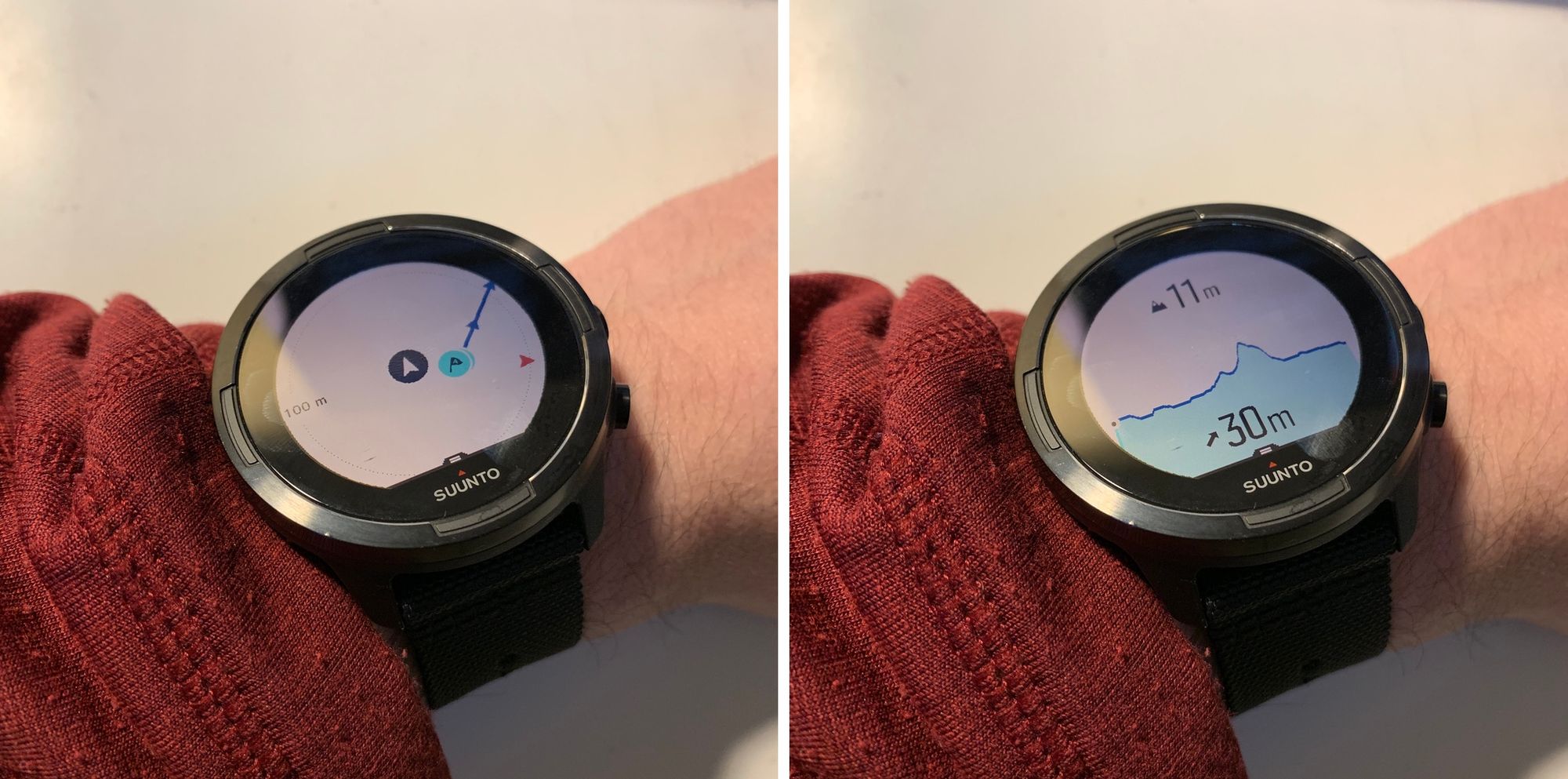

Screen 3:

- Map diagram showing breadcrumb trail and plotted route, plus any POIs

- This is a default screen and can’t be deactivated in navigation mode

Screen 4:

- A graph showing the route’s altitude profile, my location relative to nearby climbs/descents, current elevation, and remaining ascent to the end of the route

- This is a default screen and can’t be deactivated in navigation mode

When the watch isn’t navigating or tracking an activity, it uses a completely different set of screens. Here are a few of the most useful ones.

- Left: watch face showing sunset and sunrise times (my favourite watch face for daily use).

- Centre: calories burned during exercise over the course of the week (approximate).

- Right: barograph (this is very accurate).

Paper maps and compass

I decided not to bother with paper maps after all; instead, I will be carrying my trusted Garmin eTrex 20, which I’ll be using as a backup nav tool. It has complete maps for the Pyrenees and all of my data on board, and it can run for several days on a set of Lithium AA cells, even in sub-zero temperatures.

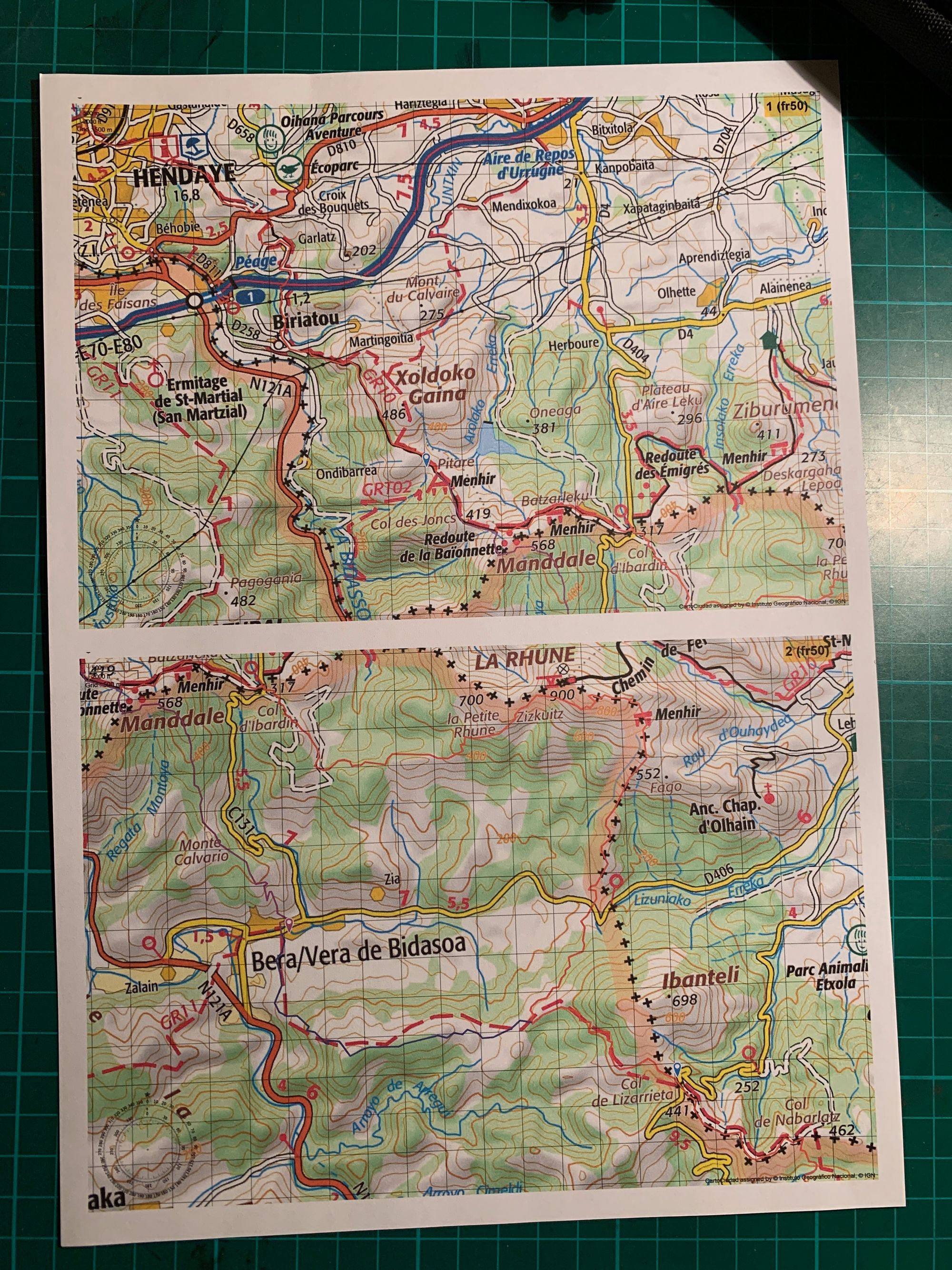

As usual, I’ll be carrying paper maps and compass purely as a backup system, and don’t anticipate using them much (if at all). For various reasons I’m not keen to arrange supply drops along the way. This means that I’ll have to carry maps for the whole trail all the way from the start, but the idea of carrying 1:50K topo maps for the whole trail is unpalatable due to the weight and bulk. Experience has shown that this isn’t necessary, though.

The maps I’ll be carrying are very overview. I’m using a set of printouts from Gaia GPS with the trail superimposed; although there isn’t much detail, they should be usable with the help of a compass and the stored data on my watch, in the event of smartphone failure. I’ll also be carrying a printed version of the Pocket HRP Guide (which can fit on a few sides of A4).

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.