Skills guide: Planning off-path routes

If your hillwalking has mainly been confined to the Peak District or Lakes, it can be daunting to visit a wilder area where there are fewer footpaths. For the first-timer in the Scottish Highlands, here’s how to confidently plan walking routes – even where there are no paths.

This feature was first published by UKHillwalking.com in December 2017.

I remember the first time I visited Scotland. I’d been walking in the Yorkshire Dales for a few years, and had climbed a good number of Wainwrights in the Lake District, but paths crisscross those areas so comprehensively that I’d rarely – if ever – had to stray from a path. Planning walks was easy because in most cases there’d be a popular path to the summit. But paths were thinner on the ground on my Scottish maps, and I found myself having to be a bit more creative with my route-planning.

If your hillwalking adventures are taking you to areas off the beaten track, here’s how to confidently plan routes and avoid problems.

Before taking on a route of this kind, make sure your basic navigation skills are up to speed. Whether navigating digitally or traditionally, carry a map and compass and know how to use them.

1. Arm yourself with information

A huge amount of information exists today to help you plan your walk. Even if no paths are marked on the map for a particular hill or objective, chances are someone else will have been that way before and written about the route, either online or in print. Make use of UKHillwalking’s route cards or ask for information in the forums, consult walking guidebooks, and keep a lookout in magazines such as The Great Outdoors, Trail, and Country Walking, all of which offer a selection of mapped routes.

By researching established routes you’ll help to hone your ability to plan your own, but there’s no point in reinventing the wheel if you’re a relative beginner. Soon enough you’ll start developing a feel for what makes a good off-path walking route. That’s probably the point where you’ll realise how great it can feel to plot and follow your own course over the mountains, away from established paths and routes others have planned for you.

2. Don’t be too ambitious

Naismith’s Rule is often used as a rule of thumb to calculate how long a walk will take. But while it can be fairly accurate for routes mostly on established paths, it tends to fall apart when you add lengthy trackless sections into the mix. You might think nothing of taking on a 15-mile tramp through the popular areas of the Lake District, but a similar distance in – say – the Fisherfield Forest is completely different, and will take you much longer.

It’s a good idea to be more conservative with your ambitions for your first few pathless outings. Set achievable goals, don’t go crazy with the mileage, and have specific objectives in mind. You’ll be more likely to have a safe and successful day on the hill.

When taking on a pathless route, planning becomes more important. Now’s the time to get out your map and start identifying useful features.

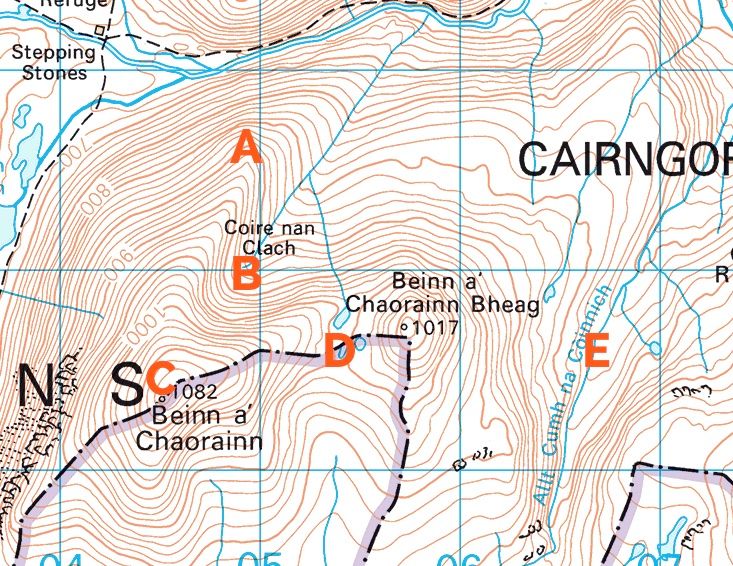

3. Know your contours

Correct interpretation of contours is the key to understanding the landscape and how to move efficiently through it. This UKH feature contains an overview of contours and how they work, but in brief, contour lines link points of the same altitude, and form concentric shapes. When the lines are close together, the slope is steep, and when they’re further apart, the slope is less steep.

Contours define ridges, flanks, saddles or bealachs, corries, valleys, flat plains, and summits. Look for areas on the map where the contours will make walking easier, or provide safe passage through more difficult terrain. For example, ridges often make good walking as long as they aren’t too steep and rocky (which you’ll be able to tell, in most cases, by examining the crag markings on the map, or by making use of the information gathered in the first step). Corries (or cwms in Wales) can be useful but are often rimmed with cliffs barring progress. Look for easy-angled valleys that lead up to a saddle or bealach – this is often the easiest line of attack on a summit.

A: Ridge

B: Corrie

C: Summit

D: Saddle/bealach

E: Valley/glen

4. Identify major obstacles

Contours don’t tell you everything about the terrain underfoot. Walking maps also display hazards that can put the brakes on your day out.

- Crags, cliffs, boulders and scree. These are marked on OS and Harvey maps, but take some interpretation. In most cases, crags marked on close contour lines equals a no-go area, and you should change your route to avoid it. Crags on widely spaced contours can sometimes indicate easy rocky ground that can be safely walked over, but it takes experience to differentiate between them. Avoiding crags is a good rule of thumb. Boulder-fields are time-consuming to cross and scree can also be dangerous.

- Rivers and burns. Make use of a bridge if at all possible. A detour from your route to take in a bridge is often worth it to avoid a river crossing. If you must cross a watercourse, cross as far upstream as possible and look for a natural fording place such as a braid or island. Don’t cross at rapids and always check the far bank for difficulties. There’s more on crossing rivers in this BMC article.

- Lakes, tarns and lochans. Perhaps obvious, but in winter these features are often buried under snow. Give them a wide berth.

Did you know that I send out regular newsletters on the outdoors, writing, and outdoor writing? Subscribe here to receive my Pinnacle Newsletter.

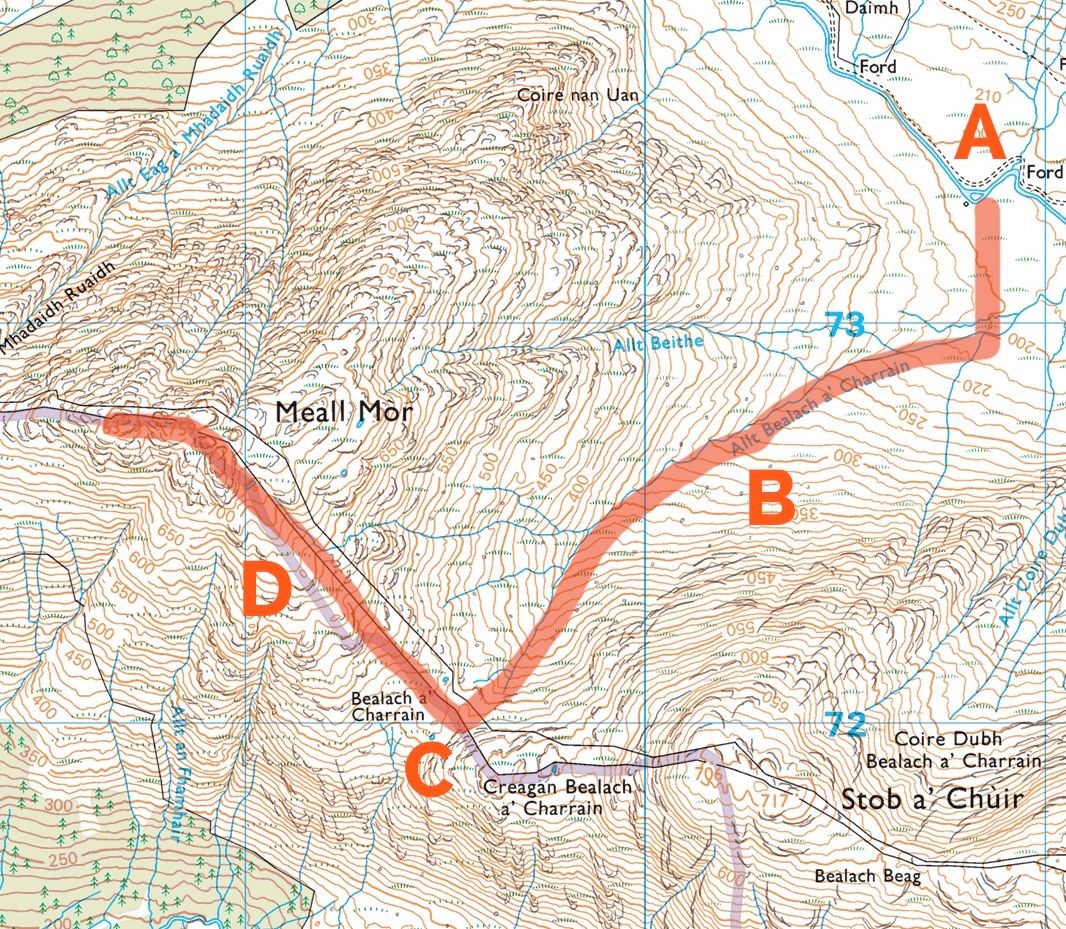

5. Follow handrails

Handrailing is a navigational technique that can really help when navigating off path. Linear features such as watercourses, fences or walls make your life easier by providing an obvious ‘handrail’ to follow. Make sure you know when to jump off your handrail to continue your route. It’s a good idea to build up a mental list of navigational landmarks to check off as you walk.

When following burns or rivers, be aware that you’ll often have to cross several tributary streams. This can be more difficult and time-consuming than you might expect!

Here’s an example of an off-path route involving two simple handrails.

A: River crossing, easily accessible via a vehicle track

B: Handrail (follow burn to Bealach a’ Charrain)

C: Landmark (Bealach a’ Charrain)

D: Handrail (fence/wall to summit of Meall Mor)

6. Anticipate and avoid difficult ground

There are many landscape features that aren’t exactly showstoppers, but which can make your life difficult. Boggy ground is the main one. The boggiest ground tends to be concentrated around lochs, in valley bottoms near rivers, in flat-bottomed corries, and on plateaus – but it can appear anywhere, even on relatively steep slopes!

Forests are also worth avoiding unless you can find a path through them. Most forests in mountain areas are dense conifer plantations that are downright nasty and time-consuming to cross, and have a habit of confusing the most experienced navigators.

7. Don’t forget the way down

The descent is more important than the ascent. You might go back down the same way you came up, or you might choose a different descent to complete a circuit. The former is usually the safer choice; you’ll be familiar with the terrain from the way up, and it’ll usually be shorter than selecting an alternative route. Unknown descents could have unexpected hazards. Always ensure you leave enough time to get down after reaching the summit.

8. Look for escape routes

Not every outing justifies an escape route. If it’s a short, uncomplicated walk and navigation will be simple, the option of turning back will usually be enough. However, for longer walks – especially ones covering multiple summits and big miles – it’s a good idea to have a backup plan in mind. Here’s why:

- Bad weather. If the weather turns out to be much worse than expected, conditions up high might become unsafe.

- Difficult conditions underfoot. Perhaps the ground is rougher and slower to cross than anticipated.

- Unsafe river crossings. If you’ve planned a river crossing that turns out to be too difficult – perhaps due to rainfall – then you will need to modify your route.

- Running out of daylight. This could be due to the walk being harder than anticipated, lack of fitness, or poor planning.

- Injury or emergency.

The best escape routes will take you back to your starting point with minimum effort. Look for straightforward valley or ridge descents, preferably with a path you can follow.

9. Plan for efficiency, especially when hiking long distance

With all the planning and map reading, it’s easy for your day’s objective to get sidelined in the excitement. What do you want to get out of your day in the hills? To reach the summit by the easiest possible route? To take in a specific location, or maybe a scramble, along the way? To take the scenic route? Your plan should aim to fulfil your day’s objective with a minimum of effort and maximum efficiency.

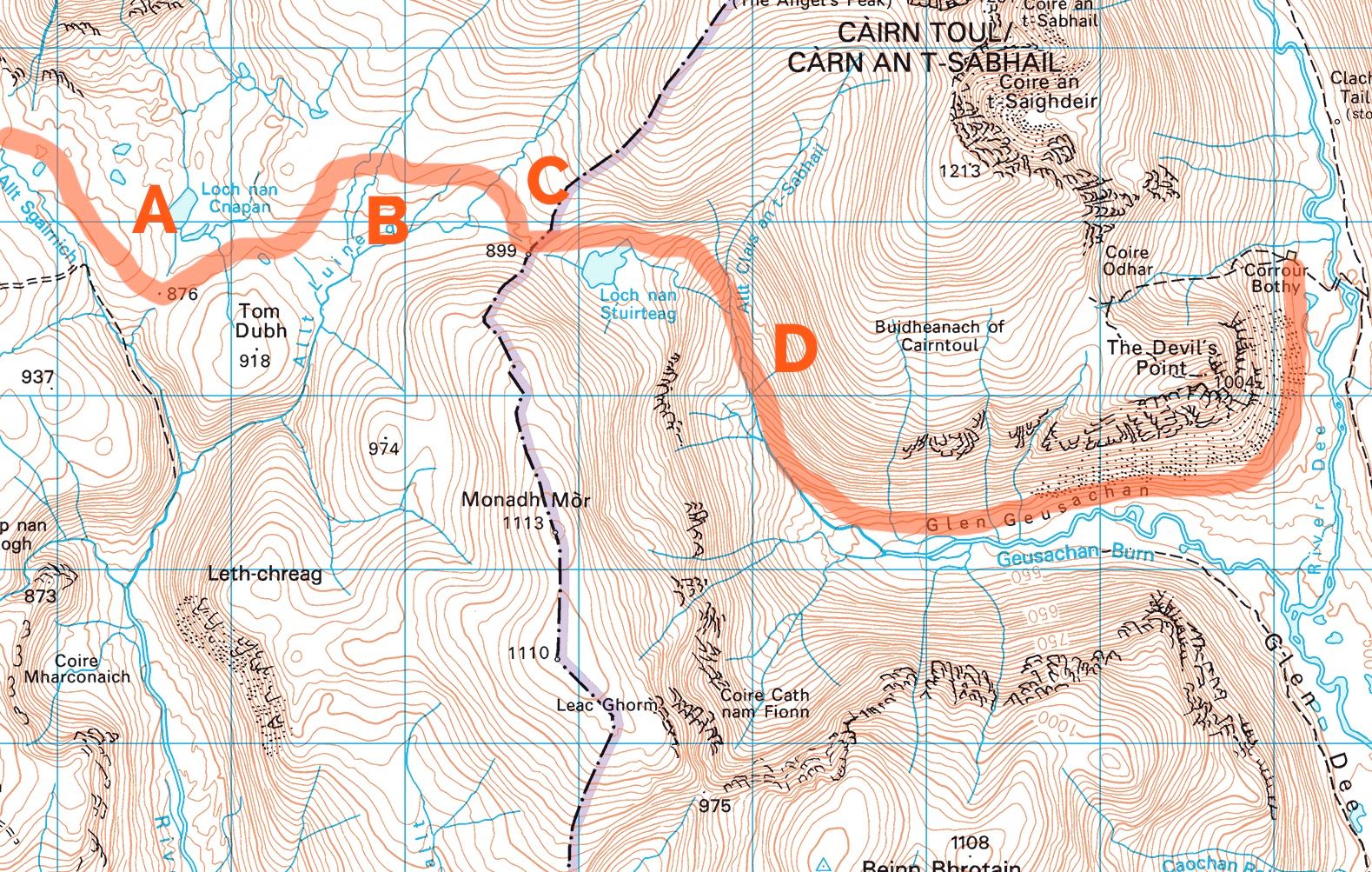

This is particularly important on multi-day trips through the hills with a big pack. If you’re backpacking through the Highlands from A to B away from well-trodden routes, keep a laser-like focus on your actual objective when you plan. Don’t be tempted to detour to too many summits – unless that is your objective, of course! Aim for the most efficient route that will take you where you want to go.

This is a leg of a long-distance walk I’ve done, showing a navigationally complex section crossing the Cairngorms. The route was designed to be as efficient as possible.

A: Avoiding the obstacle of Loch nan Cnapan

B: Heading uphill to avoid boggy ground

C: Landmark (bealach at 899m)

D: Handrail (descending the Allt Clais an t-Sabhail then following Glen Geusachan to Corrour Bothy)

10. Use paths!

Too obvious to mention? Maybe, but the reality is that most popular hills will have paths on them somewhere. It’s fun to plan free-ranging routes across the countryside but paths do make life a lot easier. If you can plan your route to incorporate paths, do so – it’s worth adding a bit of mileage to your day for the extra convenience and speed.

Smaller tracks may not be marked on the map. If you see a path going in the right direction, it’s usually safe to follow with caution, keeping your eye on the map and compass in case it veers off in the wrong direction – or peters out.

Planning a hillwalking mission away from paths and popular routes can feel daunting at first, but you’ll accumulate experience rapidly. Before you know it you’ll be able to glance at a map and see possible lines of attack for any hill. Keep those compass skills sharp, watch out for crags, and enjoy the freedom of knowing you can walk anywhere in safety.

Read more of my free online skills guides here.

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.