A Test of Mettel

In a year in which Swiss glaciers lost three per cent of their total volume, Alex Roddie returns to an Alpine peak he first climbed a decade before, and finds huge changes.

This feature was first published in the August 2019 issue of The Great Outdoors.

2007

‘My sleeping bag’s soaked.’

I could hardly stop shivering. The wind howled and another plume of spindrift blasted through the entrance of our snow cave, coating the foot of my sleeping bag and then slowly starting to melt, saturating the already soggy down. Leaving bivvy bags behind had been a rookie mistake. Then again, we were rookies.

The idea of spending a night in a snow hole had sounded great the previous afternoon, when my brother James and I had discussed it in the sun-drenched Zermatt campsite. We had our first Alpine peak all planned out. Although Mettelhorn (3,405m) is not one of the great mountains of the Alps, the guidebook recommended it as an ideal first climb in the Zermatt area – and perfect for beginning the process of acclimatising to high altitude. I was 21 years old, James 18, and we had ambitions. Before taking on Castor, Pollux or Lyskamm, though – big, serious 4,000m peaks – we had to start with something a little more modest. The ascent of Mettelhorn involved a steep walk climbing some 1,500m from our valley base, a short glacier crossing, and a final rocky trudge to the summit. It sounded perfect, but to make it feel more like a big mountain we decided to split the climb in two with a snow hole on the glacier overnight. Simple, right?

The Ascent of Mettelhorn

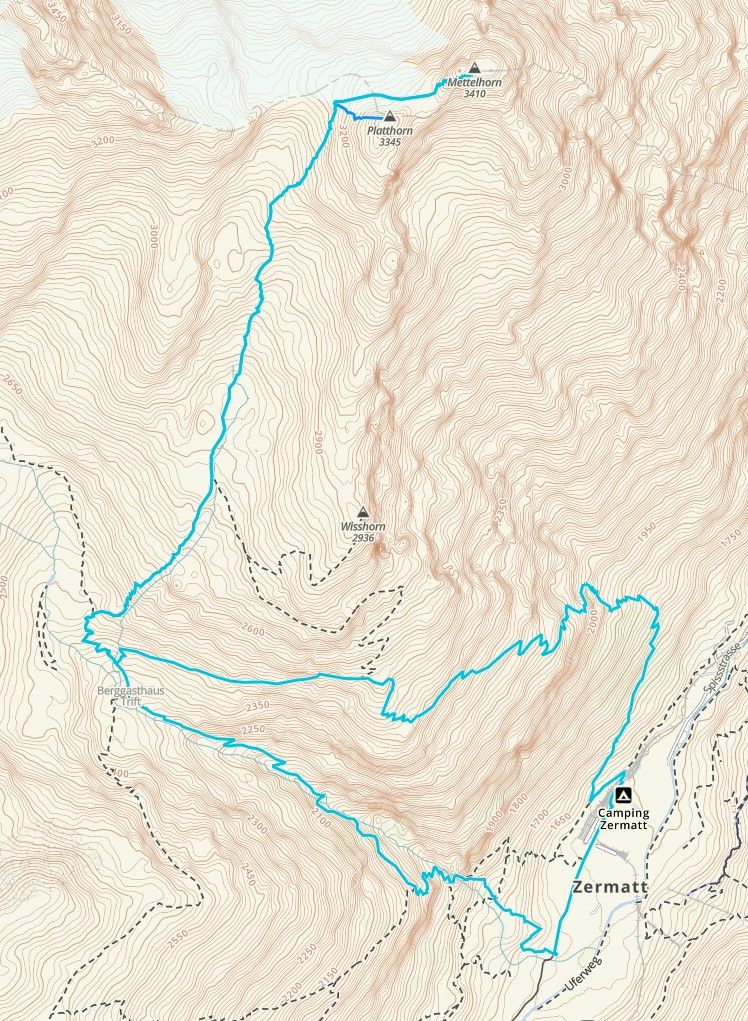

Distance: 19.4km / 12 miles

Start/finish: Zermatt town centre

Ascent: 1,895m / 6,217ft

Transport: Zermatt is easily accessible by train from Visp. The town is a car-free town; if arriving by road, you can park at Täsch and take the train from there.

Maps: Zermatt – Gornergrat Swisstopo 2515 (1:25,000)

Guidebook: Walking in the Alps: 120 Walks and Treks by Kev Reynolds (Cicerone Press)

Time of year: Mettelhorn is a summer hike, best tackled from July to September. It’s a far more serious proposition after recent snowfall.

Route notes: This is a steep and strenuous walk throughout, although paths are good until well into the second half of the ascent. The Trift Berggasthaus at 2,337m makes a good halt at about halfway. After reaching the col at almost 3,200m, there’s a short glacier crossing – crampons recommended in dry late-season conditions – followed by a final steep climb on scree to an isolated summit with splendid views. Retrace your steps back to Zermatt.

GPX file: You can view a map of my route and examine the GPX file here on Gaia GPS. I provide this for interest and general information only, and do not recommend that anyone uses it for navigating on the hill. Please do your own planning and create your own GPX files before venturing into the mountains.

Our first mistake was failing to check snow conditions or look at the weather forecast. Our second was to leave bivvy bags at the campsite to save weight. By the time we’d climbed to the top of the Triftchumme, a rubble-filled gorge overshadowed by the glacier snouts of Zinalrothorn and Ober Gabelhorn, cloud had filled in and a cold wind blew down from the intimidating heights above us. There was far more snow (and at lower elevations) than the “small patch of névé” the guidebook had led us to expect. But we set to work excavating our snow cave anyway, after finding a suitable spot where the snow pack lying on top of the glacier met a ridge of moraine. If you’ve ever tried to dig a snow hole without a shovel, you’ll know that it’s a long, tiring job; we took it in shifts, scraping and hacking with our ice axes. Eventually we hit a 45º slope of rock-hard ice, the glacier itself beneath the snow, and could dig no more. The resulting shelter was hardly a palace, but it was big enough for the two of us and would keep us warm and snug – or so we hoped.

Digging had occupied us for hours. Only as the light began to fail did we really stop to look around and think about the fact that we were about to spend the night at over 3,000m. Doubt warred with youthful optimism for a while in my head, perhaps tinged with all those tales of mountain epics I’d read about in the annals of the Victorian pioneers. The weather had deteriorated too. Cloud swirled around us, obliterating all views except in rare moments when a tattered window would peel open and grant us fantastical, dreamlike visions of crevasses and seracs in a jumble, as high above our heads as Scafell Pike was above Wastwater. Although the silence remained absolute, eerie even, I imagined that the mountains growled and whispered amongst themselves, a gaggle of trolls wondering what to do with these novices who had blundered into their kingdom. It had all sounded so simple back in the campsite. But at that moment, as the first snowflakes started to whirl and we shuffled into our snow cave to make ourselves comfortable, I felt exposed and tiny and a long way out of my depth.

Neither of us slept much that night. The roof of the cave sagged and dripped on us, turning our sleeping bags into soggy lumps. I’d never shivered so much or so intensely in my life. Snow blasted through the entrance and covered our gear despite attempts to plug the hole with our packs. I couldn’t stay comfortable on the 45º slope we were forced to lie on, and kept sliding down into the slushy puddle at my feet. We were hungry too; I’d repeated to James what I’d read about appetite being diminished at altitude, so we’d only brought a small pack of cous cous to split between us, and it hadn’t been enough.

But dawn came eventually, as it always does, and we crawled from our pit to see a world renewed. Several inches of fresh snow lay on the old pack that had been so late to melt that spring. And high above us, Mettelhorn’s summit pyramid, now visible against a uniform steel sky, looked like a Scottish mountain after a December storm, drybrushed with icing sugar. We began the final ascent anyway. The glacier was short, flat and easy, with no crevasses (or at least none we could see beneath the snow pack), but the final pull up the summit pyramid took a lot out of us both, and I could feel the thin air rasping in my lungs. The weather had started to clear too, and glorious views opened up over the wintry wonderland of the Swiss Alps in all directions. So much snow! This was worth it. And when we made it to the summit, a pinnacle high above the glacier we’d crossed and the temperature inversion 1,000m beneath it, I knew that something had changed in us. We weren’t alpinists yet, but we’d made the first step.

Only when we staggered back to the campsite hours later, feeling like veterans returning from a war zone, did we read this line in the guidebook: “If there’s been recent snowfall then the attempt should be delayed for a few days. Fine, settled weather is needed, and good visibility is a prerequisite, as is an early start.”

Ten years later…

It was always my intention to return to Mettelhorn. I remember it vividly: the cold, the discomfort, the endless snow, the feeling of being insignificant and yet elevated. When I returned to Zermatt in September 2017, I decided to revisit a few old haunts to see how the places had changed after a decade – and to see how I’d changed too.

I expected to find the climb itself a pushover. The Mettelhorn is no Matterhorn – it’s described in the Cicerone guide as a walk, and in good conditions is not much more challenging than the Pony Track on Ben Nevis. With another decade of mountaineering experience under my belt I expected it to be an easy but enjoyable outing. In 2007, James and I had packed ice axe, crampons, bivvy gear, and clothing more suited to a Scottish winter than an Alpine summer jaunt – wisely for the conditions, as it had turned out. But on a warm and sunny September day in 2017 I set out with summer walking gear and a light day pack, my only concession to the Alpine nature of my objective a pair of Microspikes.

The weather was gorgeous as I climbed steep hillsides through stands of larch and pine directly above the town. I kept up a good pace and found the walk-in a hell of a lot easier than I had ten years before, thanks to a better overall level of fitness. Looking back to enjoy those familiar views, my emotions were of joy tinged with a trace of nostalgia. The last time I’d trodden that path so much seemed to be beginning, whereas now I was in the middle of my life – and those heady climbing ambitions of 2007 had never been fully realised. While my brother and I had gone on to climb many 4,000m peaks, and other routes in the Alps and Scotland, my focus on summits and technical difficulty had been left behind as my interests veered towards lightweight backpacking. I certainly didn’t feel old as I paced uphill, but I did feel older.

Soon I entered the wasteland of the Triftchumme, filled with rust-coloured scree. This time my attention turned more to the rocky summit of Platthorn directly above than to the more impressive 4,000ers to my left. Platthorn (3,344m) is Mettelhorn’s neighbour. It dominates the walk-in and only upon reaching the little glacier at the top of the combe does Mettelhorn’s final pyramid reveal itself. In 2007, Platthorn had been a snowy peak, but in 2017 it was bare rock baking in the sun. Partly that was due to the time of year, of course. In July 2007 the winter’s snow still lingered, but a long, hot summer had stripped everything back to the bare ice in 2017, leading to very different conditions.

When I reached the top of the Triftchumme and the edge of the glacier, I thought I was in the wrong place at first. The glacier no longer came right up to the col at all, but had sunk into a huge depression at least 20-30m beneath it – far more than winter snow pack alone could account for. James and I had dug through no more than 3m of snow before reaching the ice. But where we’d dug out our snow hole was now bare rock a long way above the glacier’s surface.

The glacier had changed so much that even the ‘easy’ path over towards Mettelhorn had become a completely different proposition. Where it was once initially flat, with no steep ground anywhere, it had become a bullet-hard slope contouring around Platthorn before flattening out. I stood at the col and tried to visualise my brother and I wading through fresh snow over that landscape towards the summit. But at that moment, with the sun shining on the depleted glaciers and heat rising in waves from bare rocky slopes all around, it could hardly have felt more different.

I stretched Microspikes over my trail shoes and took a few cautious steps onto the ice. The tiny points didn’t make much of an impression and as soon as the slope began to steepen I really wished I’d brought an ice axe too – trekking poles can only do so much, and Microspikes alone aren’t great on steeper ground. Tentatively, I crept upwards, kicking into the ice to help my spikes bite, but I hadn’t gone far before I started to feel insecure. Looking down, I could see an awfully long run-out over smooth ice, ending in boulders. This was terrain for ice axe and crampons, not runners’ spikes. Despite my experience, I’d made an error of judgement on easy but consequential ground, fooled by a twisted form of one-upmanship over my own younger self – or perhaps just a trick of memory.

I heard a shout and saw a pair of walkers on the ridge to my right waving at me. “Don’t go that way without crampons,” they called. “It isn’t safe! Climb Platthorn instead if you don’t have the gear.”

I didn’t have the gear, so I turned around and climbed Platthorn instead. Mettelhorn’s summit pyramid loomed above the glacier, partially hidden by the steep slope I’d attempted to climb. It looked benign in the afternoon sun. When I reached Platthorn’s summit – arguably a better viewpoint than Mettelhorn – the neighbouring mountain that had triggered my love affair with alpinism rose above a crevassed nubbin of glacier. I could see a path wending its way between the cracks, but it looked nothing like the flat, easy snowfield James and I had traversed ten years before. I wondered how long this glacier could hold out against rising temperatures.

My irritation at having failed to climb Mettelhorn didn’t last long. Platthorn was a worthy mountain in its own right, and as I sat on a flat rock admiring the beautiful scenery I reflected that perhaps I hadn’t changed so much after all. I still loved reaching summits. I may be a decade older and theoretically wiser, but I still made mistakes judging conditions. The thing that really stuck in my mind about that afternoon high above Zermatt was how much more I had learned since 2007 about environmental breakdown, glacial retreat, and the fragile mountain landscape. Ten years before I’d been oblivious; the mountains were a playground, nothing more. But repeated visits since had shown me the glaciers retreating a little more each year. The difference after a decade was dramatic.

I might have changed less than I’d initially thought, but the mountains were changing fast, and my own role in that change couldn’t be denied: I’d flown to Geneva, after all, and I’d be flying home again. It’s a difficult question, isn’t it? How do we protect the places we love when the act of visiting them causes damage – a tiny amount on an individual level, but cumulatively huge? I don’t have an answer to that, but I do know that as a society we need to find an answer, and fast. Scientists have predicted that two thirds of Alpine glacier ice will vanish by 2100. Without glaciers, the Alps will be a duller, less beautiful, less dramatic place – and that’s before the huge impact on biodiversity, climate, agriculture, communities and industry is even taken into account.

Glacial retreat in the Swiss Alps

- In 2017, many of Switzerland’s glaciers were free of snow by July, meaning that the bare ice was exposed to rainfall and the sun’s rays for longer.

- In a study of 20 Swiss glaciers measured between October 2016 and September 2017, there was a net loss of 1.5 billion cubic metres of ice, enough to fill one 25m swimming pool for every household in Switzerland. This was among the three biggest losses since records began a century ago. It’s thought that some glaciers lost around 2-3m of thickness in that year alone.

- In September 2017, residents of Saas-Fee near Zermatt were evacuated due to the collapse of the Trift Glacier’s tongue. Monitoring had detected movement of up to 1.3m per day prior to the collapse. 150 years ago, the nearby Aletsch Glacier was around 3km longer and 200m higher than it is today.

- As glaciers continue to retreat, settlements will increasingly come at risk from floods, landslides, and avalanches. Many villages, towns and farms depend on glacially supplied water sources too.

The ice world has already changed beyond recognition in the last 150 years. We may be the last generation with the power to prevent further devastating change. I won’t tell you to stop flying to the mountains, but I will say this: if you love these places, educate yourself and try to find a way to help.

Keen to read more? There is an entire chapter about the ascent of Mettelhorn in my book Wanderlust Europe, on sale now.

Unless otherwise specified, all images © Alex Roddie. All Rights Reserved. Please don’t reproduce these images without permission.

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.