Home scanning 35mm film, the quest for cheaper analogue photography, and bringing the past back to life

Getting into the details of my own analogue revival.

Regular readers will be well aware that I have an off-and-on obsession with shooting 35mm film cameras. It began in late 2014 when my dad gave me his Olympus Trip 35 – a camera he bought new in 1969 and which has been in the family ever since (for more about this personally significant camera, which has become something of a talisman for me, read this post from last year). Other early cameras included the Pentax Spotmatic and Pentax MX, both of which I still have and still shoot with occasionally. But over the last year I have finally taken a step into the pricy world of mid-century Leica rangefinders. And, as I've shot more film and my skills have grown, I've found that I'm no longer willing to rely on the scans I get from the lab that develops my film.

Partly this is due to the fact that I want more control over my images. But mostly it is because I do not possess a magic money tree.

Confused? Most people think that film cameras are cheap, that film is cheap, because nobody uses this stuff any more and only weirdos would be interested in it. Let me explain.

When I was a boy, 25 years ago, everybody shot film because there was nothing else. And the drill looked something like this:

- Purchase your film, which probably costs less than £1 a roll, at any of a dozen or more locations on the high street.

- Slap the roll in your camera and take pictures. Most will be out of focus and badly exposed, but you're 12 so you don't care.

- Pop to your local Boots and pay them about £2.99 to process and print your pictures.

- Come back a few hours later and look through your prints. Don't share them on the internet because blogging isn't even a thing yet, let alone social media (and anyway, the computer I was using in 1997 didn't have a hard drive big enough to fit a single 2023-sized digital photo).

- Shove your negatives in a drawer and never look at them again until 25 years later when you come to move house.

In 2023, things are very different. Nobody has to shoot film any more. Or even use a dedicated camera. We all have cameras in our pockets – smartphones – that create pictures with a very specific 2020s aesthetic. Increasingly, some people are finding this aesthetic bland and mediocre. (Personally I'd call it slapdash and hideous, but let's be charitable.)

Anyway, people are looking to create pictures that stand out from the sea of smartphone pixel vomit. One way to do that is to use a real camera, mirrorless or DSLR, but it's still a very hands-off, digital and computer-y process in a world where absolutely everything is hands-off, digital and computer-y.

Digital photography is about easy automated perfection, about machines thinking and doing things for you. Analogue photography is about mistakes and imperfection – until you get good at it. And then it's about deep satisfaction in the process of gaining mastery at a tangible skill.

Another factor is that classic cameras from past decades are beautiful, tactile machines to use – and they were made to last. Some photographers find that shooting film not only produces better pictures, but the entire process is more engaging and enjoyable. There is a distinctive kind of wonder in using a tool that can continue creating pictures for multiple human lifetimes, if cared for. We live in a world where replacing a smartphone every 4–5 years is considered frugal; most phones are replaced every 2–3 years. Think about that. It is insanity. Even DSLRs and mirrorless cameras rarely stay in use for more than a handful of years before being considered obsolete.

So! Call it digital fatigue, call it a countercultural force against the digitisation of everything, but it's most definitely a phenomenon. Over the last few years demand for film has shot through the roof. Kodak physically cannot make the stuff quickly enough and have had to un-retire a bunch of technicians. Cameras are expensive and film is expensive. The race is on for several brands to spin camera manufacturing back up again, which is not as easy as you might think because the supply chains are complex. I look forward to seeing what Pentax are able to achieve in the coming years as they launch their new range of film cameras.

So, in mid-2023, here's what the shooting drill looks like for me:

- You can't buy film on the high street any more, so buy it in bulk from Analogue Wonderland or Analogue Revival and then store it in the freezer until needed. Colour film is expensive, rare, often sells out completely, and drastic price rises are frequent. Get used to paying at least £16 a roll for the good stuff – sometimes £20 or more. Most of the film stocks you used to shoot in the 90s no longer exist.

- Take pictures, constantly worrying about the cost and whether or not you're just wasting another frame.

- Order film processing via Analogue Wonderland or AG Photo Lab. You'll pay about £4.99 for processing – not too bad, eh? But do you really want prints in the year of our lord 2023? No, you want them digitally to share online. So you'll pay another £14.99 for high-resolution scans. And then another £4.99 for your negatives to be posted back to you.

- Post your film to the lab. Wait several days for scans.

- Receive an email with a WeTransfer link. Download your pictures, import them into Lightroom, and then process them as you would digital photographs.

- Receive your negatives in the post a few days later. Stick them in a drawer. At least some things never change.

- Cry about how expensive shooting film is in 2023, and constantly wonder if you should just give up and return to boring, soulless digital photography.

In short, it's complicated. And expensive. So very expensive. Some have quite rightly pointed out that the real-world costs are in line with historical norms, especially the mid-20th century, but that isn't much consolation when I've seen costs more than double in the last nine years. I've never been the kind of photographer to shoot film constantly – I always take lengthy breaks, during which I use my digital cameras. But recently I've been wanting to shoot more.

Operation Cheaper (Colour) Analogue Photography

Black-and-white film is still relatively cheap, but I prefer colour. Besides, most of the cost is in the scanning.

My plan is twofold:

- Invest in a home scanner and stop paying for lab scans. After a certain number of rolls, it will have paid for itself, but the trade-off is time/effort vs. money.

- Start shooting Kodak Vision3 cine film instead of C41 colour film (let's not even talk about slide film, which is effectively just Kodak Ektachrome at £28 a roll these days). Cine film uses the ECN-2 process, which means that fewer labs will touch it, but the film can be found for around £6.50 a roll at current prices. That's a big saving.

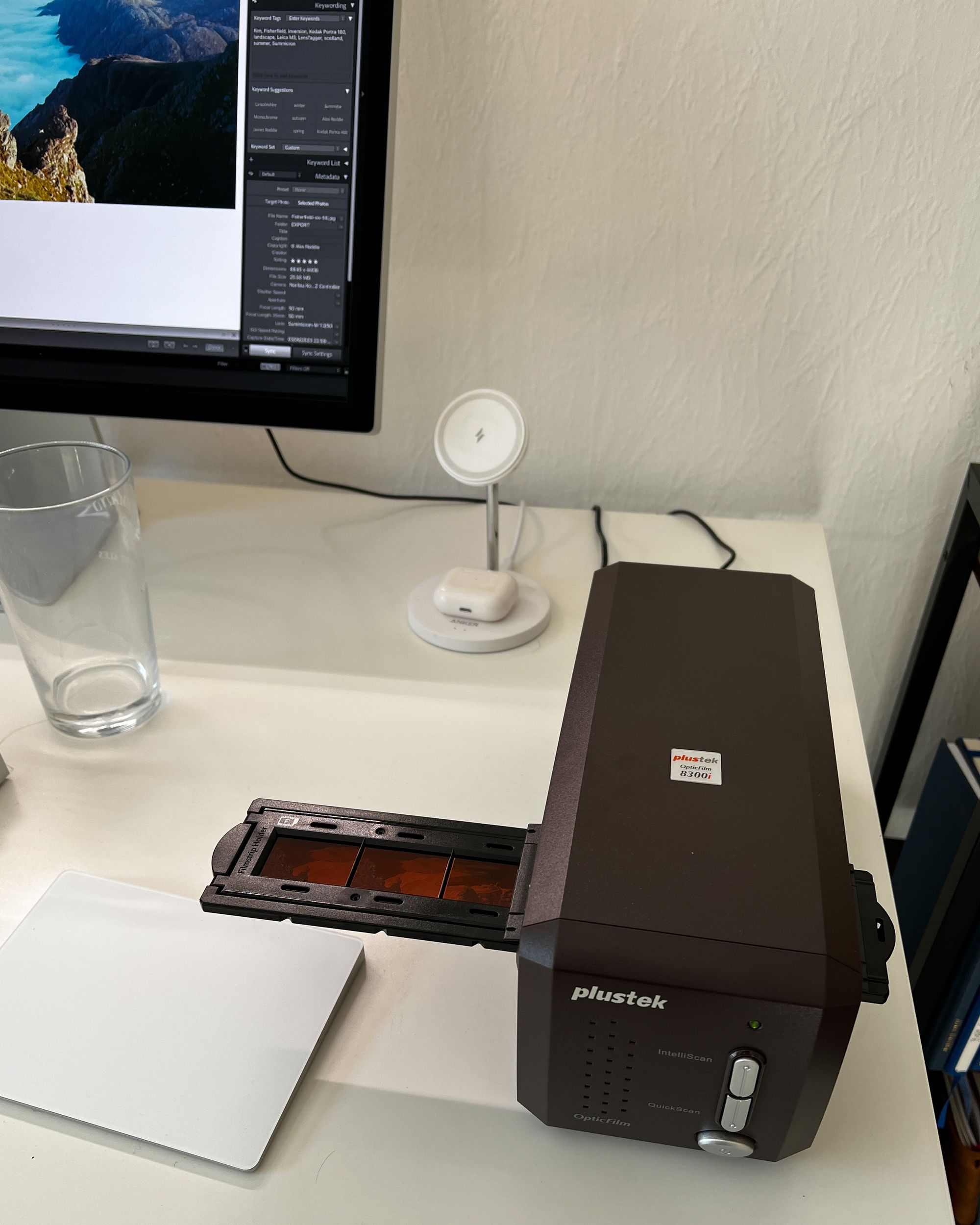

My first two rolls of Vision3 cine film are currently at the lab for processing, so I haven't seen the results yet – I'll share more about it when I can. But I have invested in a Plustek 8300i negative scanner, and that's what I'd like to talk about here.

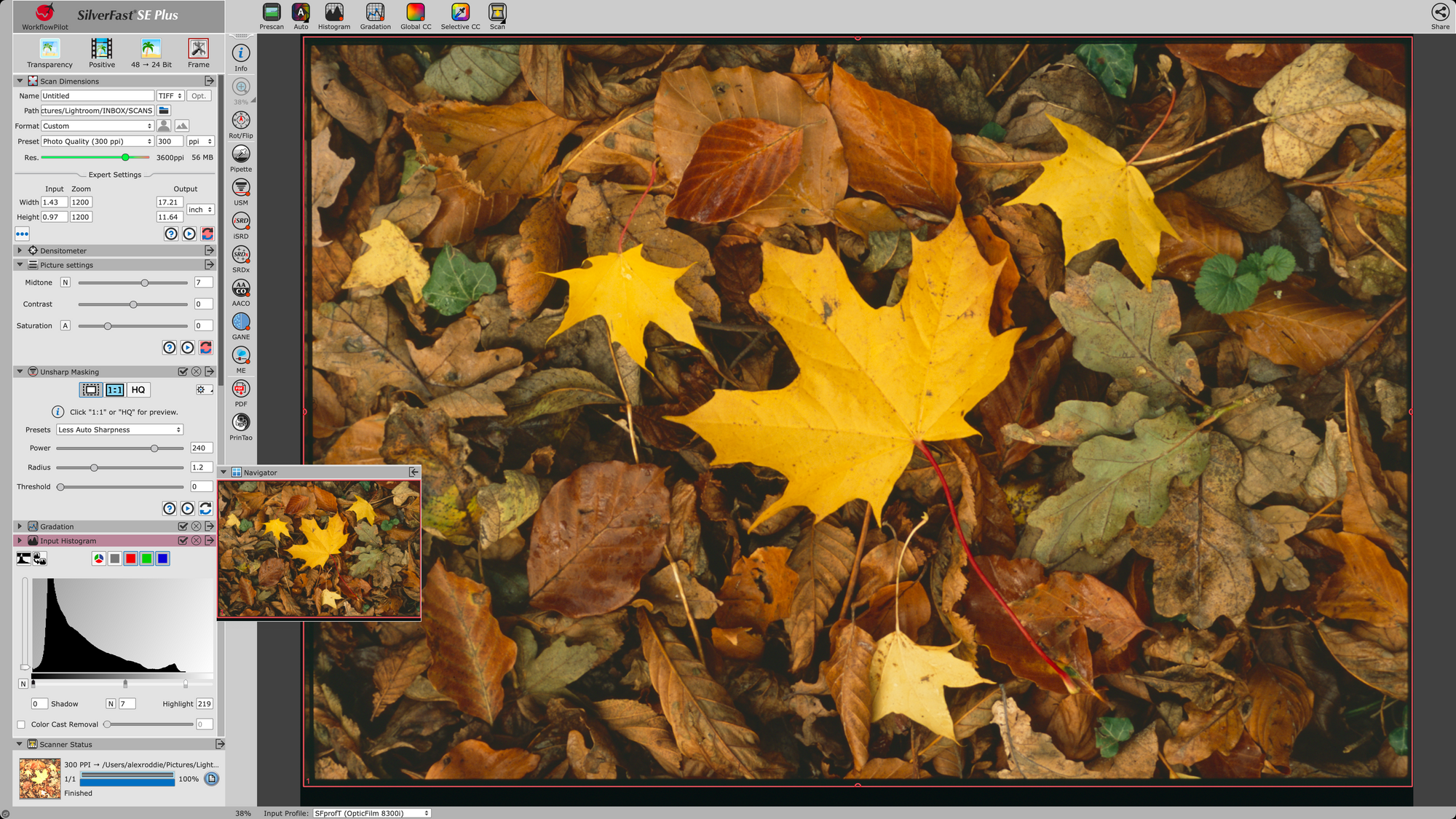

The scanner cost me £379.99. It will have paid for itself in a little over 25 rolls of film (at my current rate of shooting, less than a year). There is a learning curve involved, of course – you have to use a piece of software called SilverFast to prepare your scans, and this is not the best piece of software. On the plus side, you get far more control over the process than just receiving a WeTransfer link from the lab. Is the negative a bit thin? You can tweak settings to compensate for this. Is the colour balance a bit weird? Again, you're in control. Although it takes an hour or more to scan an entire 36-frame roll, I have found myself really appreciating this extra stage.

There's an intangible benefit, too. My pictures feel more like the physical artefacts they truly are. Before, I was receiving scans first, then negatives a few days later (which I'd rarely look at, as in my head the scans were the canonical images). Now I simply receive negatives. It is up to me what I do with them. It's a subtle mindset shift, but it helps me to feel greater ownership over the images and the process.

Would I find home development just as rewarding, cutting out the professional lab altogether? Maybe – and it's certainly something I'm considering. But for now I think I'm happy with scanning my film after letting someone else develop it.

Here are a few images from my first few rolls (a mixture of Washi X, Fujifilm C200 and Fujifilm Superia 400). I'm very happy with the results. A well-exposed 35mm negative can yield extraordinary dynamic range. Scanned at 20 megapixels, the images are sharp and full of detail, with beautiful colour, and (technically at least) more than good enough for publication in books or magazines.

Bringing the past back to life

When I started shooting film again in 2014, I didn't really think about the scanning stage. A few high-street labs were still processing film back then, and you could tell them to give you scans on CD. But the results were often deeply mediocre: low resolution, bad dynamic range, excessively sharpened, weird colour, and covered in dust and scratches. I didn't know any better and just thought that's what film looked like.

To this day, treasured memories exist in my Lightroom library in this form. Some people like the 'imperfections' of 35mm film, such as dust and scratches (or even light leaks). I don't. I like creating high-quality images. I like the fact that a camera made 40 years before I was born can create photographs that anyone would be proud to publish today. But – and this is the beautiful thing about all this – you can always go back and scan your negatives again.

This afternoon, I put a few negatives from those first few 2014 rolls through my scanner, and recreated the images in much higher definition. Below is perhaps the best example. The original scan (left) was tiny, had far too much contrast, and generally looked bad. The new scan (right) has more realistic colour and a far larger file size. Of course, I have only uploaded a small version to the web; the full-size scan is 5,000 pixels across on the long edge. The image still isn't particularly sharp, but that was due to my poor skill level at the time the image was captured.

Best of all? Scanning images that I never got around to scanning at all back in the day. Plenty of photographs have just been sitting in a drawer as negatives for the last nine years, but I can now look at them on my computer screen and share them here. Here are two examples from the very first roll I put through my Olympus Trip 35, a few days after my dad gave it to me.

My own analogue revival is, I feel, at its peak right now. I've seen an increase in my skill levels over the last few months. Consistently shooting with manual, meterless cameras has expanded my knowledge of exposure – as well as my photographic eye, I think. With the image quality I'm now consistently able to achieve with this gear, I've started using analogue photographs in published work. When viewing my material in books and magazines, I'll be interested to know if any readers are able to point out which images are digital and which are film.

© Alex Roddie. All rights reserved. Don't reproduce these images without permission.

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Subscribe here to receive my occasional personal newsletter in your inbox. (For the fun stuff, please consider subscribing to Alpenglow Journal instead!)