Generative AI will not make you a better writer – it will destroy creative writing as a way of expressing the human experience

'People, not machines, made the Renaissance.'

This essay is entirely my own opinion, and is not a statement of policy for any of the organisations or publishers I work with.

There's a lot of noise at the moment about generative AI in creative fields: photography, illustration, copywriting, creative writing. The technology has come on a long way in a short period of time. AI-generated art is being used in online articles. There are debates about the ethics of AI-generated photos. And, in the world of writing, it is having a huge impact: Amazon is being flooded by AI-generated books, small publishers are being inundated by a tidal wave of AI spam submissions, and writers are starting to wonder if there is a legitimate place for this tech in their work.

I understand the temptation. Writing is hard! It takes many years, if not decades, to get good at it – a path littered with unfinished projects, failures, rejections. It's hard to earn a living from it unless you're good, lucky, commercial, or benefit from some form of privilege (such as knowing the right people). Ideally all four. There are more opportunities for writers today than there have ever been, but that doesn't mean there are any shortcuts to excellence. Or even competence.

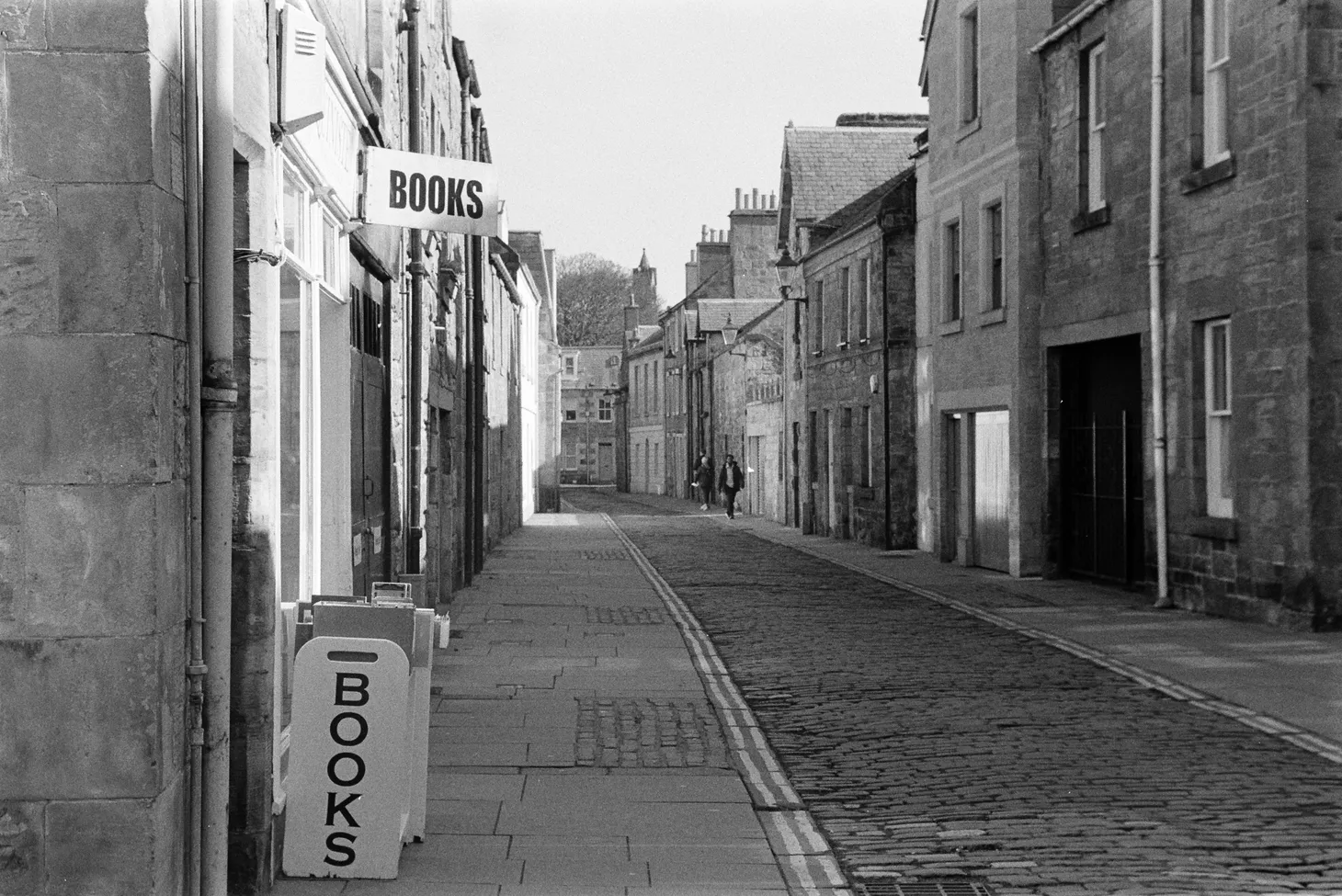

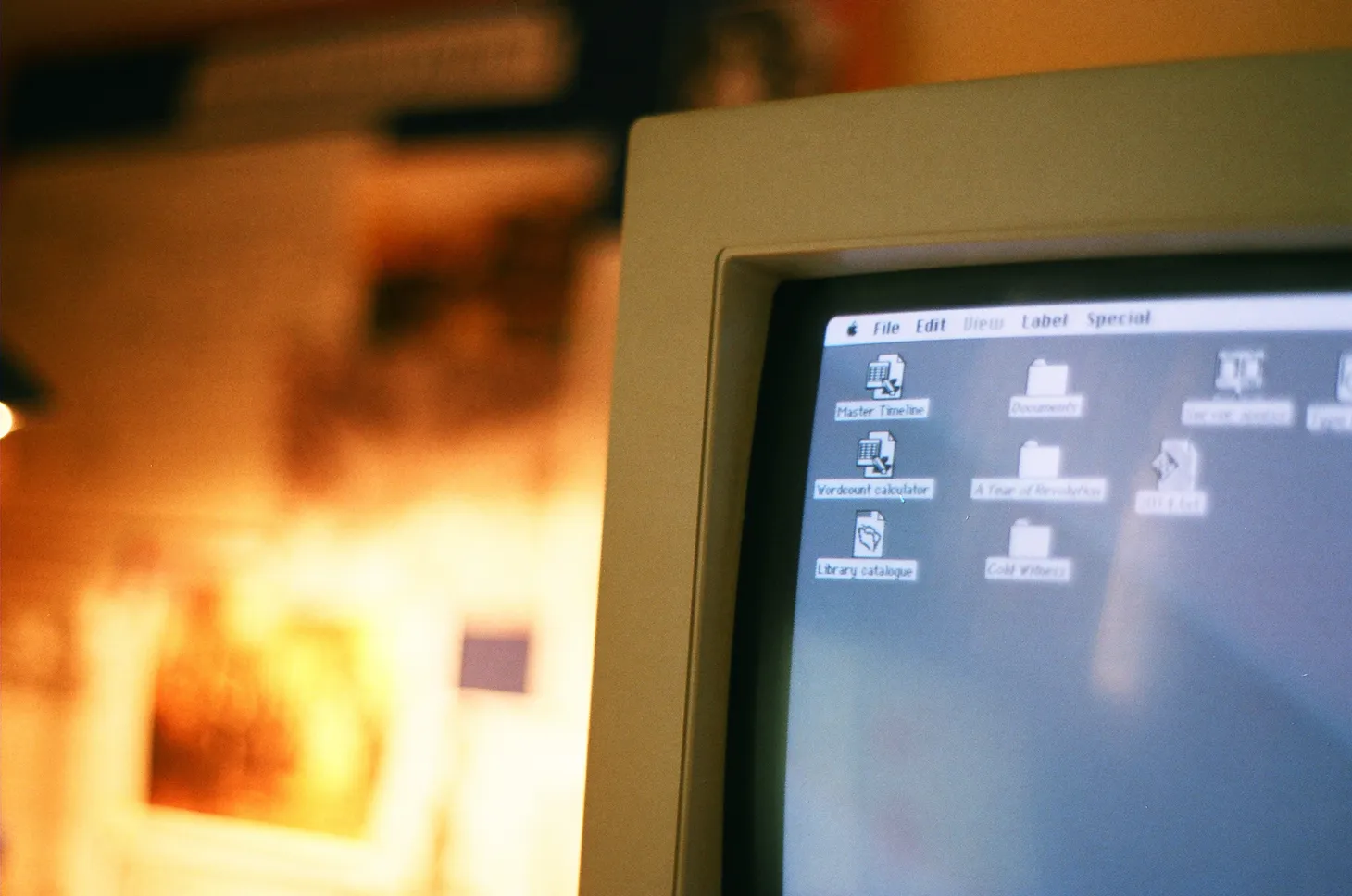

Writing is not really writing. It's thinking. This can take many different forms, and can even be embodied – I'm a big believer in the idea that writing, thinking and walking are fundamentally the same thing – but there are no shortcuts around it. Don't believe me? Books written by typewriter did not show a leap in quality over books that were handwritten. Word processing didn't improve their quality either. All else being equal, a computer made in 1990 is just as capable of writing the most sublime, uplifting fiction as a computer 10,000 times faster made in 2023. Tool choice certainly affects the nature of the creation, but every development in writing tech has been about comfort and convenience, not quality.

Developments in office communication from memos and typewriters to emails and WhatsApp have not led to lower workloads or increased efficiency, either. I get hundreds of emails a day. The signal/noise ratio is atrocious. Streamlining and automating work just leads to more work.

Don't misunderstand me – I'm not saying there are no advantages in modern methods of communication and creating. I'm also not saying that we should shy away from automating non-creative tasks to an extent. I'm dreadful at mental arithmetic, for instance, and would not relish a return to a world without calculators. But arithmetic is procedural and logical. Although some elements of the craft of writing can benefit from procedure and logic, at its core this is about the translation of human emotion and experience. The expression of an internal state. That can't be automated.

You might think that the superficially convincing output of a Large Language Model such as ChatGPT is doing this, but LLMs are little more than highly advanced predictive text systems trained on vast data sets of other people's writing. If you believe that such programs can be creative, what does that say about your beliefs regarding creativity?

Using generative AI to create a story, or assist in its creation, means that you are avoiding some of the thinking. I believe that AI-generated content does not qualify as writing, in the same way that images manipulated beyond a representation of what the photographer experienced (note careful word choice; not the same thing as saw) is not photography.

What problem does generative AI actually solve here? We are already drowning in more writing than anyone can possibly hope to read, so we don't need to be able to make more of it faster. In fact, I'd argue that the challenge of the future is one of curation and selection, not more and more output. Maybe AI can help us come up with ideas? Sure, if you are looking for mashups of ideas everyone else has already had. Originality may be overrated, but point of view (which cannot exist without individuality) is king. It should not need saying that, in my field of travel and adventure writing, AI-generated ideas are worthless.

It follows that the only real potential advantage is in improving the quality of our writing. But let's think about the ways in which writers can actually improve. There's personal life experience. There's noticing and observation. There's reading a wide variety of material by other writers. There's studying the craft of writing. And, most importantly, there's doing more writing – a lot more of it. My belief is that social media is already attacking our ability to notice and observe, as well as (for many of us) gobbling up some of the time that we might once have used for long-form reading. Writers who are considering using generative AI in their work are not going to be serious about studying the craft of writing. And if we are choosing to offload the hard parts to a machine, we cannot hope to improve by writing more either. The muscle that is not put under strain will never grow strong.

One of the curious things about AI-generated content is that it has revealed the robotic and uncreative nature of much human-written work. But I'd argue that this is a capitalism problem, not a creativity problem.

Creative intent is the key thing, apologists say – we'll never give up that even if we leave some of the details to machines. But generative AI undermines creative intent by robbing us of the thinking process. When we are not deliberate about the words we use, we surrender creative intent and our individuality. The ChatGPT-assisted writer's own voice and perspective dissolve in a bland word soup of other minds.

The more we become accustomed to relying on machines to do the hard things for us, the less capable we'll become of doing these things ourselves – and the more machine-like we will become. When we outsource our reasoning and creativity to a chatbot, not only does our thinking become more rigid and conformist, we are actually eroding our ability to think. Nobody can remember phone numbers any more, can they? That's because we've outsourced that part of our minds to machines. But our personhood is not intrinsically linked to our ability to remember phone numbers. Or do mental arithmetic, for that matter.

We don't fret about this because we're told that automating these things frees up time and headspace for the things that humans are uniquely good at. The things that reside in the soul, like creativity and intuition and emotional expression. But if we surrender these things too, even by an inch, then what is left? If we retreat from the notion that there is something ineffable about human nature that cannot be appropriated and automated by machines, we demean the very concept of personhood. I can't think of anything more antihuman.

If we surrender this ground then I foresee the end of writing as a way of expressing human experience. Maybe the end of being able to express human experience – and therefore the end of our inner selves experiencing anything at all, because our inner selves will no longer be distinct from our external technological support systems. I don't want to be dramatic, but think about this. We will lose the ability to discern machine-generated content from the true feelings of a human soul. And, as we become more machine-like the more we are trained and modified by the systems we now serve, the distinction between the two will fade to static.

The search engine began as an attempt to make human knowledge more accessible, but it soon began imposing its own form on that knowledge. Today, finding useful information on the internet is arguably harder than it has ever been (thank God for Wikipedia). The same thing will happen to writing if we allow it to be contaminated by generative AI. We think that we can control it, that we understand its limitations, but it will devour us. Not only is the medium the message, we are shaped by the tools we use far more than we like to believe. We will become the medium and forget the message.

I'll close with a few quotes by Jaron Lanier from his excellent book You Are Not A Gadget: A Manifesto.

People degrade themselves to make machines seem smart all the time.

When people are told that a computer is intelligent, they become prone to changing themselves in order to make the computer appear to work better.

Computers can take your ideas and throw them back at you in a more rigid form, forcing you to live within their rigidity unless you resist with significant force.

People, not machines, made the Renaissance.

I'm taking a break from social media at the moment, so if you've read this and found it interesting or useful, please share it with someone else!

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Subscribe here to receive my occasional personal newsletter in your inbox. (For the fun stuff, please consider subscribing to Alpenglow Journal instead!)