What survives in the record: a Glen Coe hill day from 15 years ago today

Every now and again, I dip into my Lightroom library and journals, curious to see what I was doing 10, 15, or 20 years ago on this day. On the 6th of April, 2009, my brother James had just arrived in Glen Coe and was keen to experience these mountains for the first time. The rest is history; he never moved back down south, started a new career as an adventure photographer, and has now lived in Scotland for much more of his life than I have.

One of the things that has always interested me, as a sci-fi nerd with an interest in history (and therefore time travel – watch this space) is how moments are lost in time. We experience something and it is gone, converted to memory and whatever record we choose to make. My own memory is startlingly bad... or maybe just extremely selective. I'm very good at forgetting things. This is why I take photos and write detailed journals.

Memory and record, record and memory. They blur into one another, don't they? One is influenced by the other. They become each other's substance. It's impossible to record everything, or even most things, about any experience. The gaps become fluid, perhaps filled by organic memory if it's jogged in just the right way, or perhaps filled with the extrapolations of record that the mind fools itself into thinking is memory. We look at a photo and imagine we can remember how cold the wind felt.

I thought it would be interesting to look at one specific day, 6th of April, 2009, and set down what precisely remains in the record. And what survives only in flawed organic memory. And how the whole lot has shifted over the last 15 years.

Here are the facts.

Photographic evidence

Surviving photos: 10 by me. Only two exist in decent quality and resolution in my Lightroom library. The rest are tiny, grainy thumbnails that I had to pull down off an ancient Facebook album. For some reason I never archived them properly at the time, and Facebook has started applying brutal compression to older media, including removing sound from uploaded videos and reducing images to only a few kilobytes – you've been warned. Digital records can be so fragile. Nothing lasts for long on the internet. Remember – there's no such thing as 'the cloud', it's just someone else's computer.

The better images

The not-so-good images

In mid-2009 I was using a Kodak Easyshare C813 with a broken LCD, which means that I had to just point the camera in the general direction of the scenery and press the button. I always bought the cheapest cameras I could find because I was constantly damaging and destroying them in the mountains (and also because I was skint). Dark days for my photography!

Almost certainly the worst camera I've ever owned

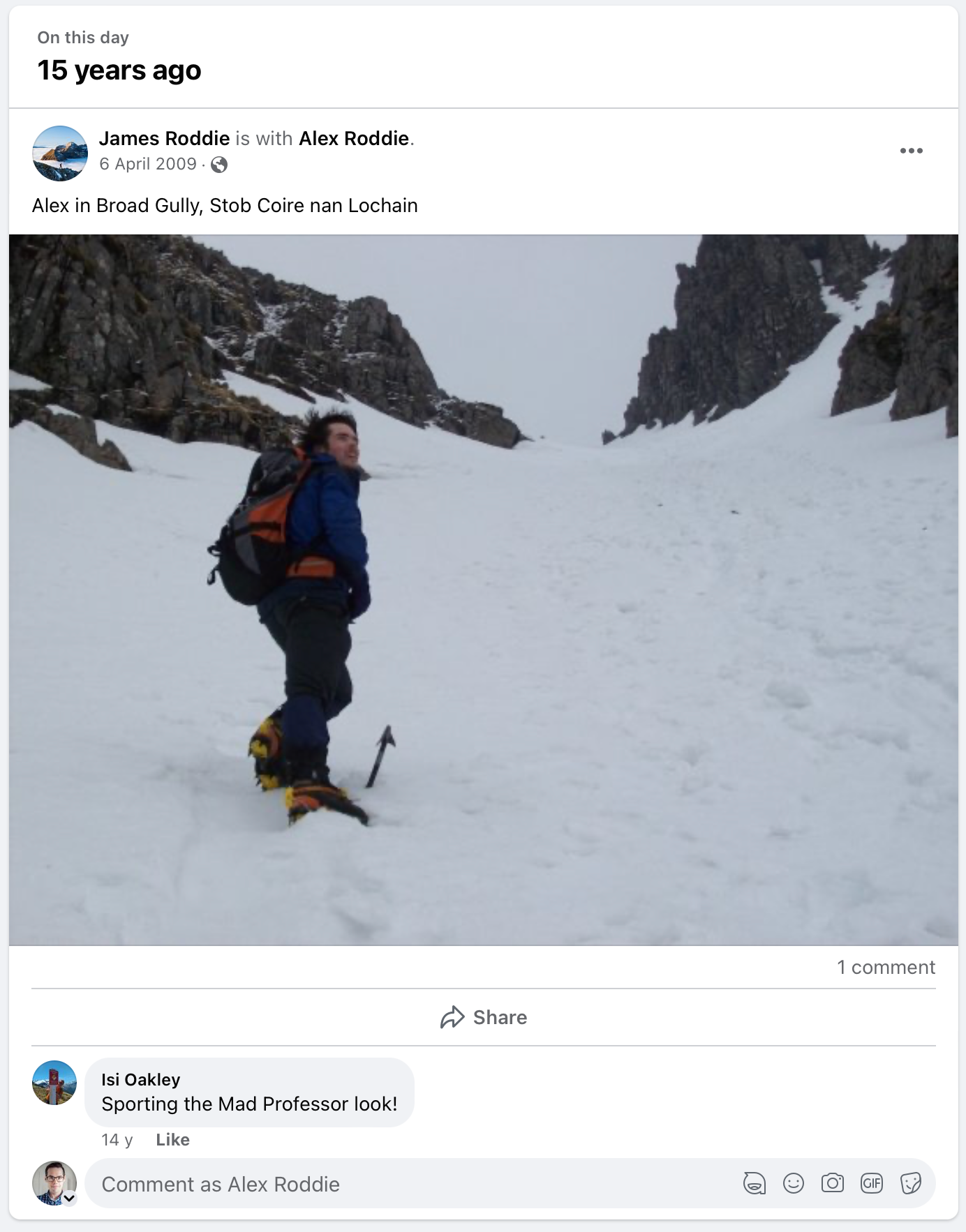

There is one more photo, which James took. I'll let it speak for itself. It may have been dark days for my photography, but my hair was having a party.

Documentary evidence

The documentary evidence consists of:

- My mountaineering logbook;

- The long-defunct blog Glencoe Mountaineer;

- Several Facebook posts.

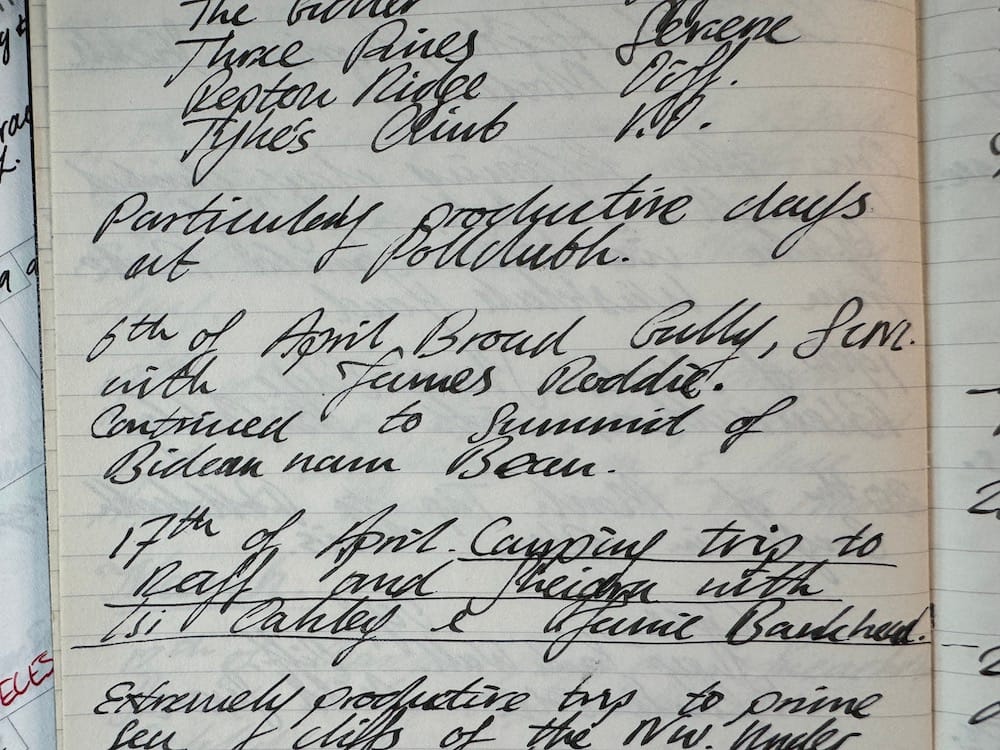

Here's what it says in my mountaineering logbook. A brief entry, as most of them are (I've been making entries in this book for 21 years now and it's still only two thirds full).

Glencoe Mountaineer vanished from the internet long ago, but fortunately I had the foresight to archive it all (in immortal Markdown) in 2018. Here's the entry.

Monday, 6 April 2009 - Coire nan Lochan today

As my brother James has recently arrived in Glencoe for the summer, but has done no walking hereabouts, we went for a wander into Coire nan Lochan for an introduction to the layout of the region. The weather was surprisingly good today, with only a little cloud hovering at about 1000m and no rain. Another surprise was the quality of the snow. The lowest snow patches were somewhat mushy, but as we moved into the coire things firmed up nicely.

Most of the easy gully lines are 'more or less' complete. Broad Gully and Forked Gully appeared fine, although it's anyone's guess what the turf is like in the middle of Forked Gully. Boomerang and NC were complete but the mixed steps appeared rocky. Buttresses are almost entirely free of snow. Dorsal Arete is probably climbable but cannot be considered in condition by any stretch of the imagination!

We walked up Broad Gully on largely excellent neve, with only the odd patch of softer snow. Clearly it had frozen overnight. The pack consisted of mostly homogeneous re-frozen grains, well bonded and consolidated. No avalanche risk whatsoever.

Upon visiting the summit we were treated to an excellent view of Bidean--looking very Alpine today--and Stob Coire nam Beith.

Let's take a look at what pops up in my Facebook memories. Here are three screenshots.

The memory

The thing that interests me about the records above is that my main organic memory of the day is barely mentioned – and there's a strong bias. Have you noticed it?

My mountaineering journal says 'Continued to summit of Bidean nam Bean [sic]'. Those of you who know Bidean will realise that Broad Gully tops out on the summit ridge of Stob Coire nan Lochan ('SCNL' in the journal entry). There is a connecting ridge that heads across to Bidean, which is a completely separate and higher peak. The 'pinnacle of the mountains', to translate from the elegant and perfectly descriptive Gaelic name. Then we would have made the descent of Coire nam Beithach directly back to the Clachaig.

I think it's interesting that almost all of the evidence above relates to Broad Gully and Stob Coire nan Lochan. The onward journey to Bidean, and then down Coire nam Beithach, is mentioned only in the most perfunctory way, and only in my logbook. There aren't even any pictures showing this segment of the journey! Yet my actual memories almost exclusively focus on Bidean and the first part of the descent.

I clearly remember climbing the long, sinuous ridge to Bidean in cloud ripping over the buttresses, marvelling at how wild the place felt, how fiercely glad I was to be there, and how pleased I was that I could introduce my brother to my favourite mountain. It was his first ascent of Bidean, and my fifth. In a whiteout, we stood on the summit – a featureless mound of snow. I took a compass bearing. We descended. I remember that the way down felt like real mountaineering: a steep, uncompromising snow slope with an abyss to the right and wind howling in from the left. Crampons, footwork, ice axe passed from one gloved hand to the other at each turn. The dominant emotion was that this was an extraordinarily real moment.

For me, every ascent of Bidean has felt different, come with its own distinct flavour or lesson or vibe. But none of this survives in the physical record.

All memory is flawed, all records are incomplete

The interesting thing about this particular day is that the records I chose to keep reflect my biases at that time. I was obsessed with climbing and felt an insistent need to prove myself, rack up the ascents in my winter logbook. Since starting the Glencoe Mountaineer blog (which was pretty new in April 2009) I also felt the need to post 'conditions reports' for other climbers.

This was a time when blogs were the most important source of such information. Facebook was only useful if you were friends with other climbers, but most climbers weren't on Facebook; it was seen as faddy and nerdy by most, and not many people over the age of 21 had an account. UKC was of course long established, and people posted conditions reports on the forum all the time. But this was before the UKC winter conditions page existed. Blogs were it. Many climbers posted detailed updates on their blogs every single day.

Looking back, I find it interesting that I didn't even mention the section of the day over Bidean. Did I assume that other climbers would only be interested in the graded routes on SCNL? Did I want to avoid spoiling my reputation as a climber who got routes done? Was I worried that a hillwalker vibe would somehow put people off, or change how people thought about me?

The point I'm getting at here is that any historical record is subject to biases and selectivity. People record what they deem important at the time. The rest is lost.

And my memory? It's only been 15 years, but already my memory of this outing hangs from the surviving photos as if they were tent poles. I think I remember what it felt like to climb up the gully because I can look at the picture and imagine myself there. But, if I'm honest, I don't. It's a memory that the record has conjured in me.

I think that my only real memories of this outing are from Bidean – the sections that were barely recorded. Perhaps because they were barely recorded.

All moments are lost in time, and perhaps that's fine, but they do have an afterlife – and maybe their ever-changing echoes grow in significance as we grow older, perceive more about what the experience meant and how our own morphing perspective has altered them. Is there a lesson here? If there is, it's one I learnt some time ago: keep more detailed journals, and write about your feelings and observations rather than just what happened. You never know when you'll want to inhabit those moments once again.

Another lesson? Nothing stored on the web lasts very long. Digital information decays and is lost; it must be archived correctly, and even then physical artefacts still have the edge.

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Subscribe here to receive my occasional personal newsletter in your inbox. (For the fun stuff, please consider subscribing to Alpenglow Journal instead!)