'Embracing constraints taught me to love them'

Tip of the hat to The Cramped, one of my favourite blogs, which pointed me in the direction of this fascinating piece: 'A tale from “ye olden days” of graphic design that taught me to love and embrace constraints'.

This post from Mike Rohde is a look back to the distant world of graphic design and magazine layout in 1988.

Traditional graphic design in “ye olden days,” before computers revolutionized the design scene, was slow, labor-intensive, and, much of the time, a royal pain in the butt to do.

However, I feel fortunate to have been a design student when I was because it taught me to love and embrace constraints.

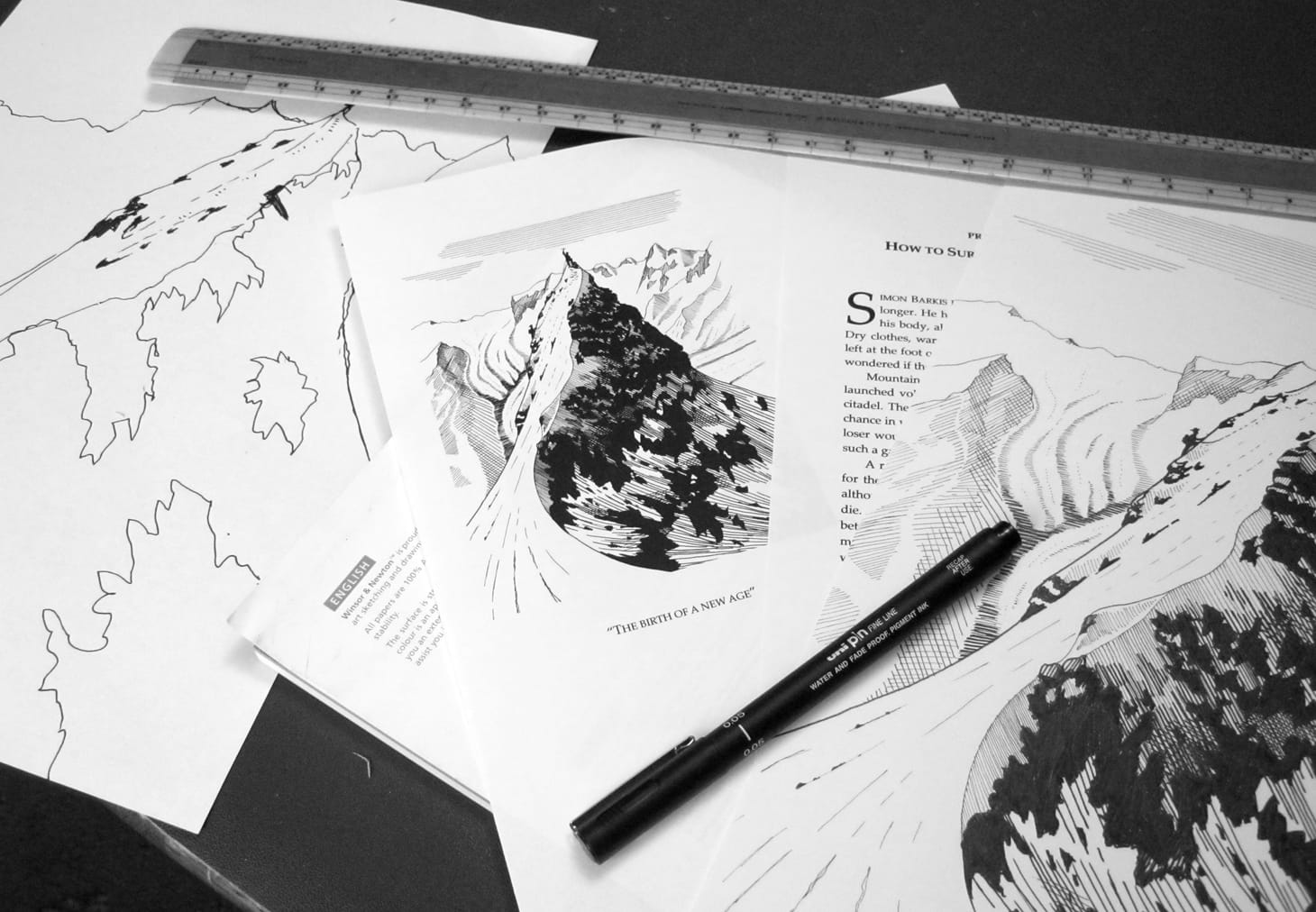

I recommend reading the post in full. It examines a fascinating process that, to a modern eye, appears byzantine: 'filled with layout boards, non-repro blue pencils that made lines invisible to production cameras, technical ink pens to create registration marks, and typography and photography output on photo paper.' Hardcore analogue, in other words.

The world Rohde describes is one of painstaking, highly specialised analogue techniques that had to be used because there were no alternatives. It's a world well before my time – in 1988 I was only two years old. I have no experience of taking an idea to printed page without the benefit of computers. One of the things that really strikes me, reading through this post, is how many little things computers do for us that we take for granted – invisible benefits most people simply never have to think about, such as automatic kerning. Modern designers have to understand kerning too, but modern desktop-publishing software removes a lot of the manual grind behind the scenes.

Nobody is asking to return to this world. Least of all me.

When I speak to people about my passion for analogue methods and tools, there's sometimes a misconception that this is motivated by nostalgia, or perhaps a notion that older methods were better from start to finish. But there's a fundamental misunderstanding here. Sometimes my geeky curiosity about vintage technology plays a part, I'll admit, or my beliefs about modern product design; sometimes my contrarian nature and interest in vintage style, too! But mostly it's due to the concept of creative constraint.

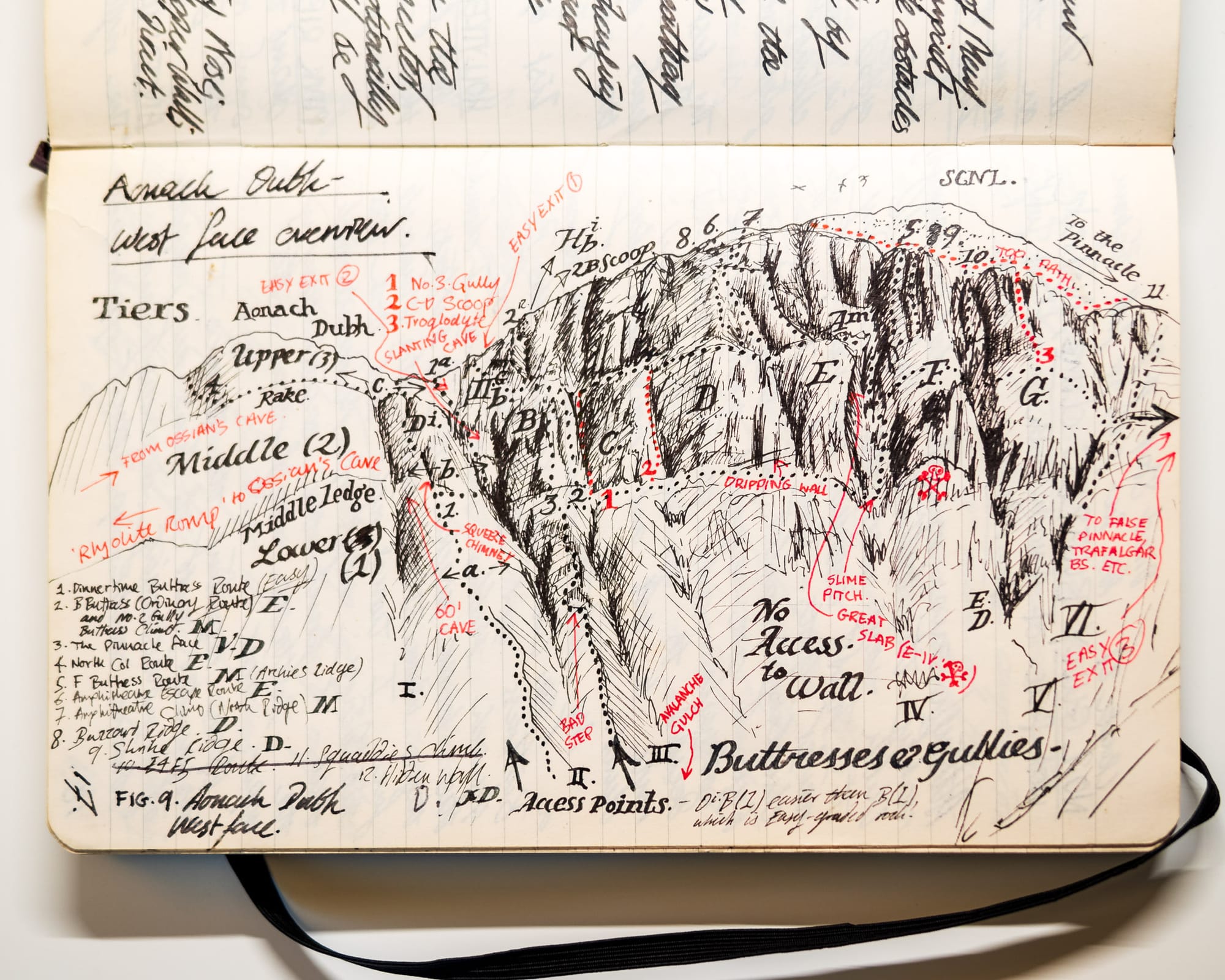

In his post, Rohde explains how he wanted to make more creative layouts than his phototypesetting machine (which only had ten typefaces) would allow. He ended up approaching the problem from a new direction: using a photostat camera to replicate glyphs from type specimens, then individually typesetting and kerning the glyphs by hand. As a result he was able to create some uniquely creative layouts.

We can learn much from this distant world of magazine production in 1988. Computers may have removed a lot of the manual labour and sheer tedium from the creative process, but they have also simplified and flattened it. Many people find that ideas struggle to thrive in an environment where creation is comparatively easy. Where we can press a few buttons and a result appears, with relatively little thought required in the process.

Rohde:

Through this process, I learned to love constraints. Getting beyond the ten-font type constraint required me to think creatively and solve problems differently.

My approach when I face constraints is:What CAN I do with the resources available?Is there another way to think about this problem?What would someone with a growth mindset do in this situation?What if I turn the problem upside-down? What ideas might fall out?

Creative work does not happen on the computer screen, an environment almost perfectly tuned to destroy focus and flow. It happens in the human mind. Making connections is a mental process. Therefore, any tool that exerts a bit of pushback – that requires the mind to work harder by virtue of its simplicity or other inherent constraints – can lead to richer and more focused creative work. Not everyone's brain works like this, but mine does, and the same is true for countless other people.

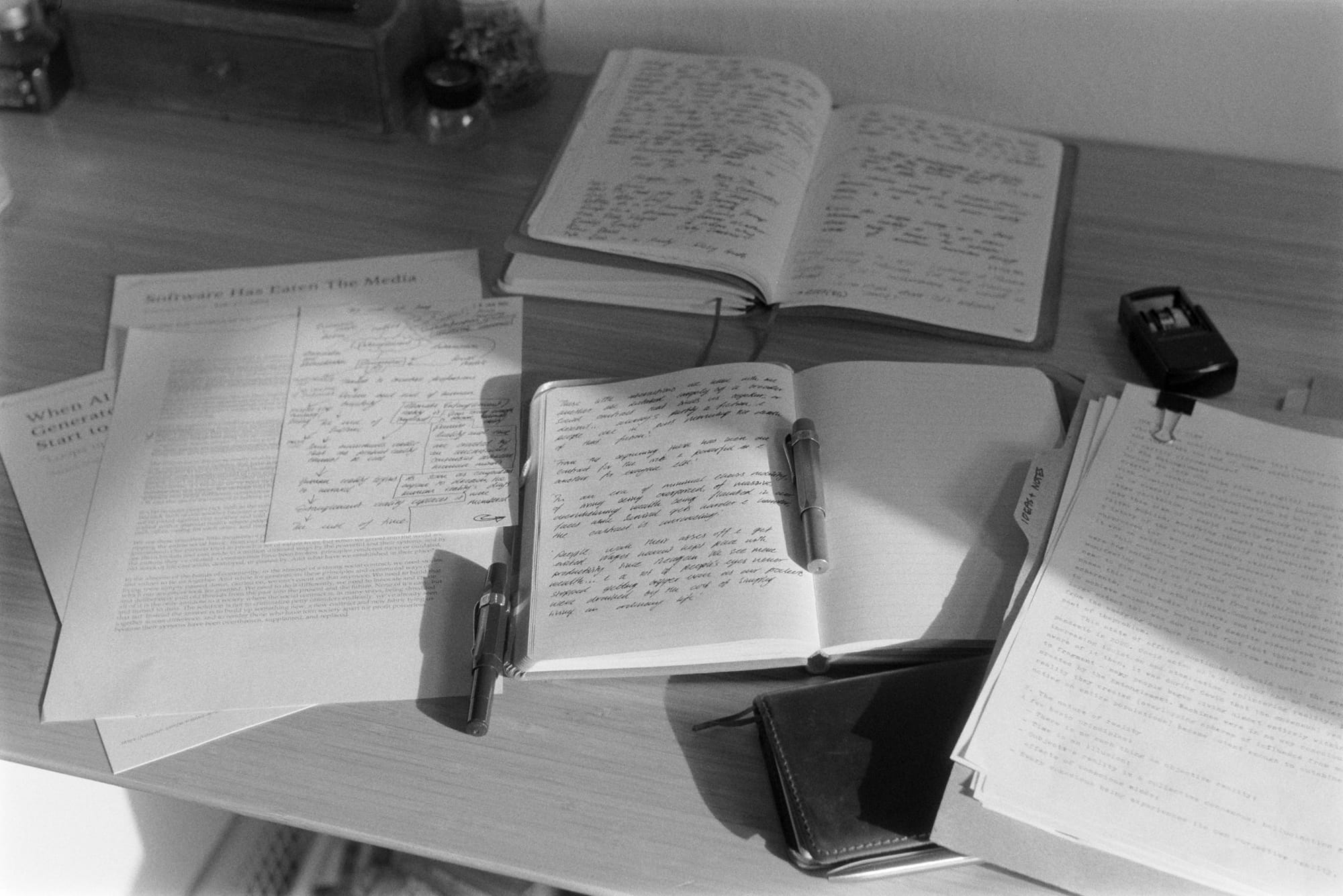

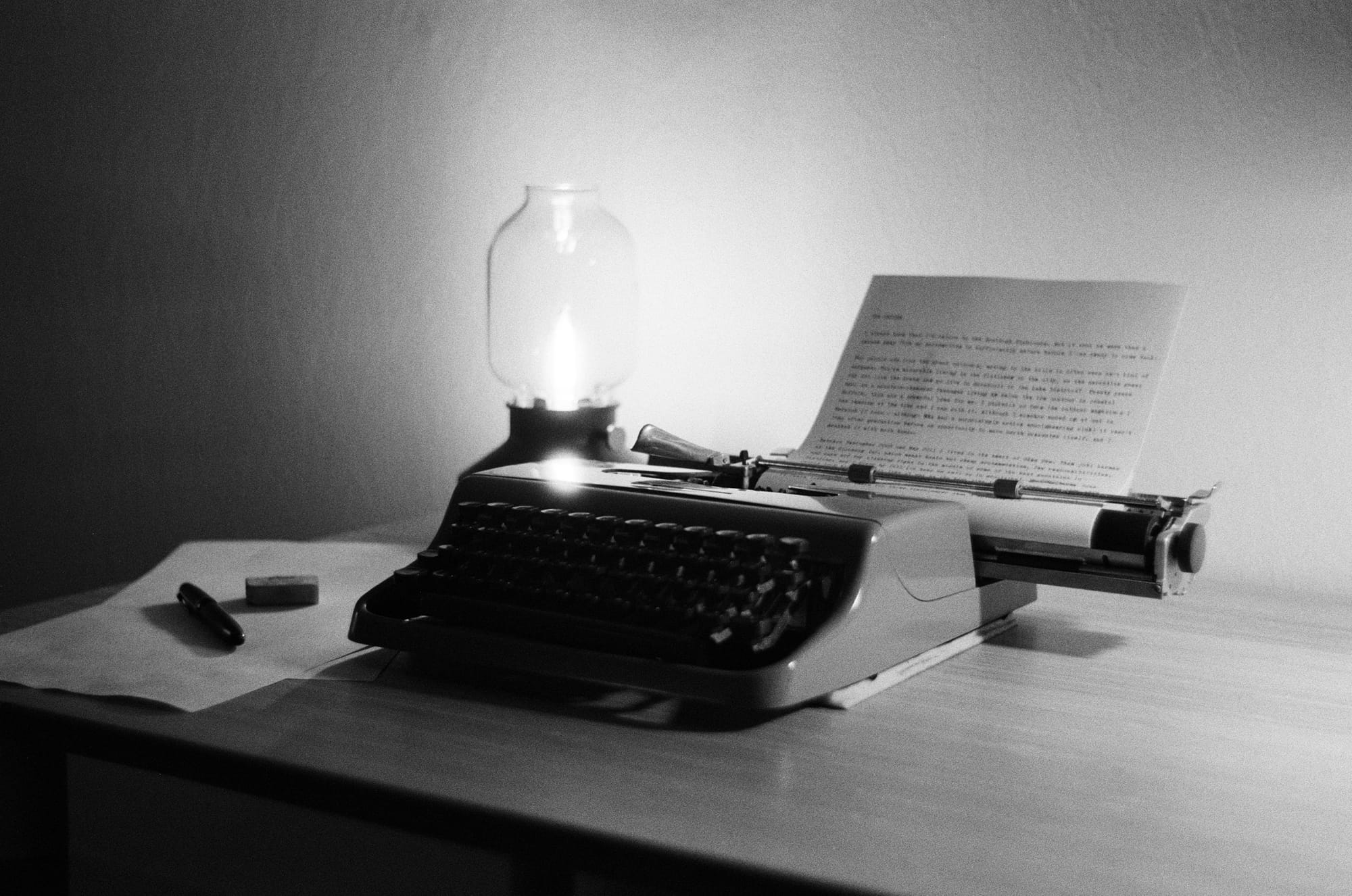

This is why I believe so strongly in simple tools: pen and paper, pocket notebook, typewriter, film camera, Markdown and plain text, physical books, light table. I use these in conjunction with the full range of modern software-based tools used by all other writers, editors, and photographers. Looking at this with my editor's hat on, if you try to submit a story to me as a typescript, accompanied by 35mm slides, sent by post, then I will take a dim view. That's not a creative constraint. That's just annoying! But if you use these tools as part of your creative process, and then send in a high-quality submission via the modern approved digital channels used by everyone else, I will respect you.

Obviously there's no guarantee that the work will be better than if you'd used purely digital methods, but it does show that you've applied thought and consideration to your process. That counts for a lot in a world where many writers are tempted to just type a prompt into ChatGPT and call it a day. (To be totally clear, I will not respect you if your work has been contaminated by generative AI.)

For me, it's a simple fact that I create better work when I introduce creative constraints. Better doesn't necessarily mean faster, more profitable, or more marketable, God knows. But it does mean better.

I don't want to return to a world of hardcore analogue workflows where absolutely everything must be done by hand because there are no better tools.

I want a world where we all have access to a range of tools that exert differing levels of creative friction – and where we can mindfully select these tools for the job at hand. A world where writers aren't considered hopeless Luddites if they simply create higher-quality work with a pen or typewriter, or if they find it easier to focus with these tools. A world where photographers who prefer to shoot film aren't still judged by some as pretentious hipsters. A world where computers respect our attention and focus and don't try to strip all human thought out of the equation. A world, to be frank, with a bit more colour and flare, where more of us dare to step beyond the boring hegemony of Google Docs and Microsoft Word and Lightroom and InDesign and black plastic cameras with 56 different auto modes.

Last words from Rohde:

You might be surprised to find solutions hiding in your constraints.

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Subscribe here to receive my occasional personal newsletter in your inbox. (For the fun stuff, please consider subscribing to Alpenglow Journal instead!)