First steps in medium-format film photography

For me, creativity has never been about the final result, and that's certainly true of photography. There's so much more to enjoy, to learn, to engage with. As someone who finds modern digital photography soulless, who has spent a decade learning how to shoot 35mm film, medium format was always going to be the logical next step. It was only ever a question of time.

This article has been cross-posted to my Substack. Please bear with me while I work through how to divide posts between the new Substack publication and my blog – Alpenglow Journal is still on its way!

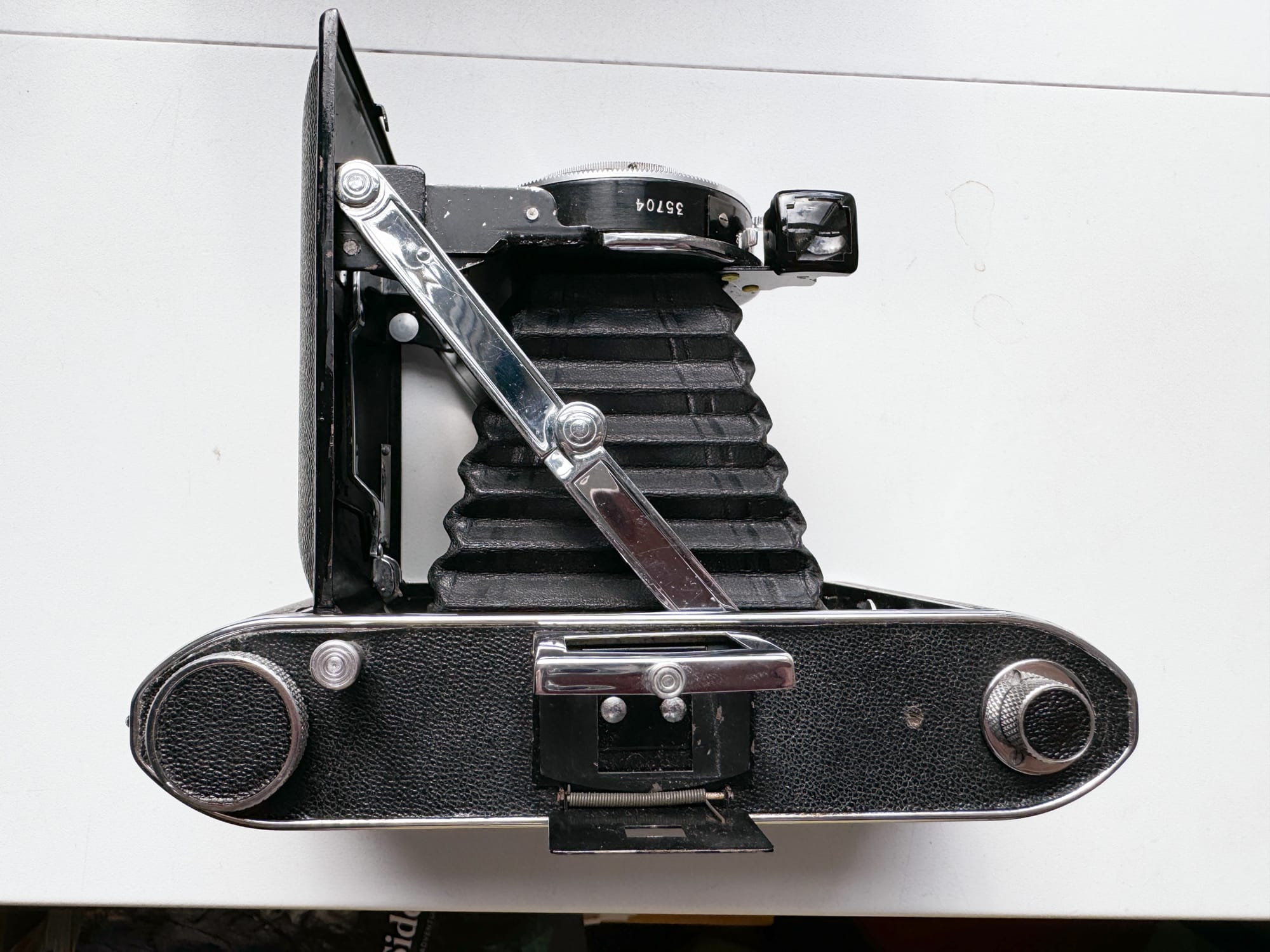

I can't say what tipped me over the edge from 'medium format is cool but I'm ok with 35mm' to actively looking for cameras to buy, but as usual I blame the eBay algorithm for my first purchase. Oh, look – a gorgeous Ensign Selfix 420 in black and chrome, described as fully working... and listed for a fraction of the price I'm used to paying for a working film camera these days. A few minutes of research revealed that this folding bellows camera was manufactured in England in the 1940s, takes 120 film, and can shoot images in either the square 6x6cm or rectangular 6x9cm formats.

What is medium format?

Loading the Ensign Selfix 420 – and, folded up, compared to my Leica IIIc in size (the smallest 35mm camera I possess)

120 film was introduced by Kodak in 1901 for the launch of the Brownie No.2, and has been in continuous production ever since. For many decades, it was the standard format for consumer snapshot cameras, but after the rise of 35mm (which most people think of as 'film' these days) 120 became the preferred choice for many professionals – especially those looking for the best balance between image quality and portability. Photographers looking for the best quality at all costs have always shot large format.

However, 35mm was used by professionals right from the start, especially photojournalists, adventure photographers, and others who demanded compact and lightweight gear. So standard did the 35mm frame eventually become that today's professional digital cameras have 'full-frame' sensors about the same size as a 35mm negative.

Today, during the great analogue revival of the 2020s, medium format is a niche. I think it's fair to say that most analogue photographers today are shooting 35mm – it's cheaper, the cameras are smaller, and the trade-offs make more sense for most people.

But I've always been a bit awkward and like doing things differently. Besides, I enjoy a good learning curve, and I'm getting to the point where I feel like I've mastered shooting 35mm film – from a technical point of view, at least.

Cameras that shoot 120 film vary from box cameras well over a century old to highly advanced and capable SLRs. Generally speaking, the older the camera the simpler it is. I've always been interested in mid-century folding cameras, which offer an intriguing mixture of exceptionally high image quality in a lightweight, pocketable package. Some of these cameras have modern conveniences such as rangefinders (usually uncoupled), but many do not. Almost all of them force you to do your own thinking when it comes to exposure, which is fine by me – I already shoot with meterless 35mm cameras.

These cameras reward skill, patience, and experience. They punish sloppiness, haste, and lack of knowledge.

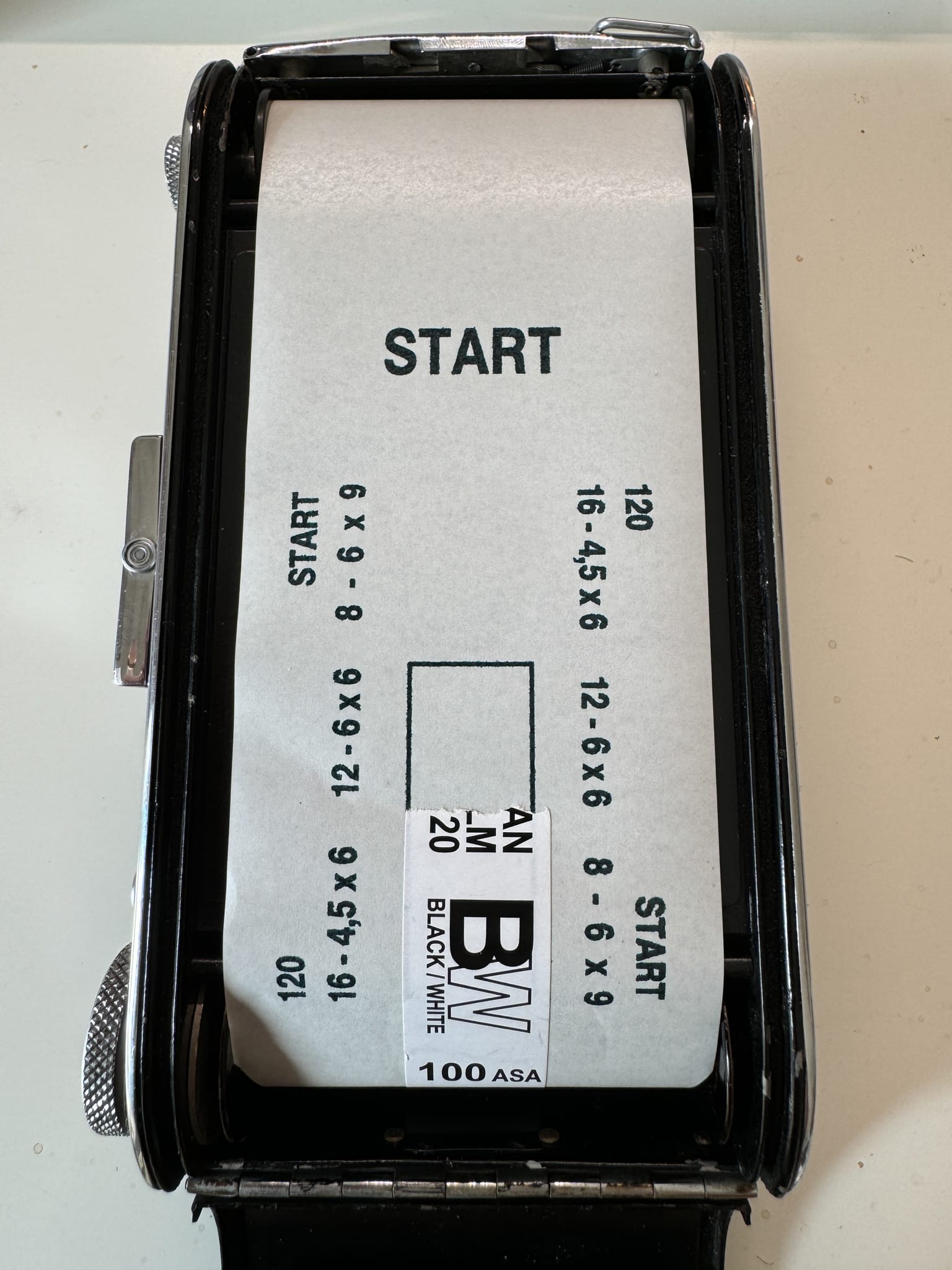

A roll of 120 film looks very different to a 35mm roll. There's no metal canister to protect the film. Instead, it's taped to a strip of backing paper, which is directly rolled around a plastic spool and then secured with more tape. Inside the camera, the mechanism transfers the film from one spool to another. It isn't rewound after exposure. Instead, the photographer must open the camera, carefully secure the backing paper using a bit of sticky paper, and protect it from light. It all feels a lot more archaic and fiddly.

But let's be honest, nobody is diving down one of these rabbit holes because they want an easy life, are they? I believe in slowing down, in being intentional, in saying no to automation, in full engagement with any creative process. Medium-format film ticks all of these boxes – but it also comes with tangible benefits.

What's so great about medium format anyway?

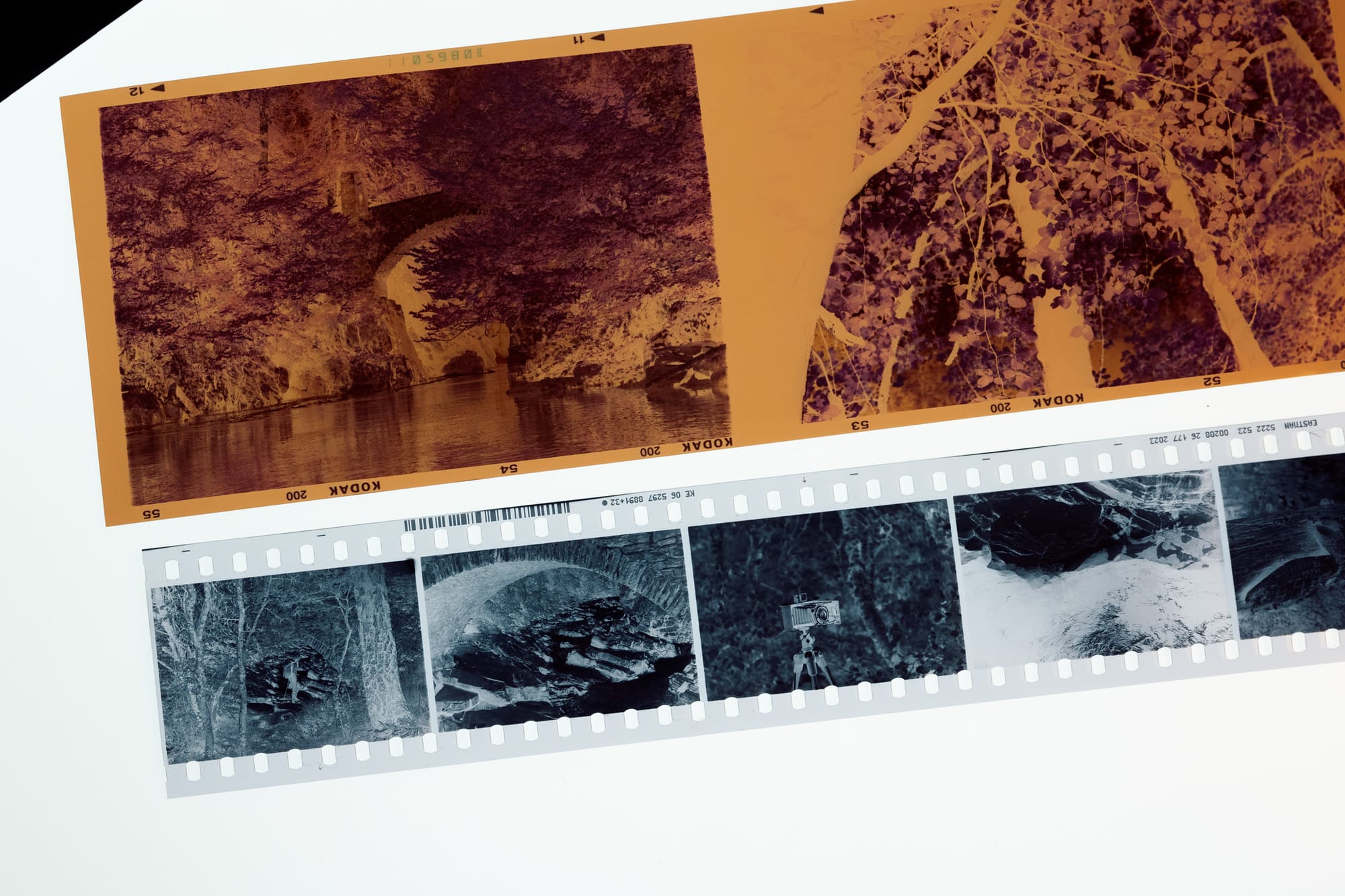

Two words: massive negatives.

Even a 6x6cm negative is much bigger than a 35mm negative, and 6x9cm is dramatically bigger, as you can see from the picture above. This translates to a number of benefits:

- All else being equal, significantly higher resolution. 35mm is already high enough resolution for many purposes, but medium format gives you much more. Opinions differ, but anecdotally I've found that 35mm can give good detailed when scanned at up to about 20MP (beyond this you're mainly enlarging grain, depending on the film used). Scale this up appropriately for medium format. I haven't shot enough rolls to say anything definitive yet, but my current scanning rig can yield 36MP digital files, and I'm seeing no evidence of hitting any limit. Put simply, if you are looking for analogue image quality that in some circumstances can rival full-frame digital cameras, look no further than 120 film.

- Higher resolution means greater perceived sharpness, again all else being equal; many older medium-format cameras have primitive lenses that aren't very sharp at wider apertures. I happen to enjoy the blurry, glowy look of ancient lenses wide open, but you might not. More modern medium-format cameras have exceptionally good lenses that will perform well at any aperture. The Pentax 6x7 series is often cited as the pinnacle if you're looking for the best possible quality.

- Much smaller grain. A film that looks grainy in 35mm (for example, many ISO 400 films) will look clean in 120. And a film that looks clean in 35mm (Kodak Ektar 100 is a good example) will look like polished velvet in 120.

- Shallower depth of field. Just as a full-frame camera gives you shallower depth of field than the tiny sensor in a smartphone camera, a medium-format camera goes a step or two beyond full frame. Once again, all else must be equal. Many older medium-format cameras have slow lenses maxing out at f/4.5, and a lens this slow is not going to give you the subject separation that an f/1.4 portrait lens will offer on full frame. And less depth of field can also be a disadvantage (see below).

- Dust, scratches and other particles on the negative don't show up as much on the scan, because they aren't magnified as much. If you scan in a dusty environment, or if your ancient camera is scratching your negatives, this can be a real benefit – much less time in Lightroom cleaning up scans with the healing tool!

- Different aspect ratios. A 35mm camera will only give you an aspect ratio of 3:2 unless you crop after shooting, but some medium-format cameras have selectable masks that can change the aspect ratio before shooting. For example, my Ensign Selfix 420 can shoot either 8 images at 6x9 or 12 images at 6x6. Other cameras offer alternatives such as 6x7.

- Folding medium-format cameras can be very compact and lightweight.

- The intangibles. You might have as few as 8 frames per roll; this can really help to focus you on composition and technique. And the simpler cameras require more skill and attention to use as well. Many photographers find that shooting medium format makes them a better photographer.

What are the main downsides?

There are some pretty fierce trade-offs with medium format, and depending on your priorities they might be enough to make you run a mile:

- The expense. Typically, a roll of 120 is about the same price as a roll of 35mm... but you only get 8 or 12 shots instead of 36. Development is sometimes a pound or two more expensive as well if you use a professional lab. Overall, shot for shot, cost is a lot more. But you're being more intentional and aren't taking as many shots, so I'd argue that this is only a disadvantage if you want it to be.

- The faff factor. It's easier to ruin a roll of 120 because there's no lovely metal can to protect the film. Careless handling, bright sunlight, moisture and heat are all potentially more damaging. If you are not careful when loading and unloading, possible issues range from poor film flatness to light leaks. Even winding the film on to the next frame is more awkward; forget about just pushing a lever with your thumb. On a folding camera you'll need to wind manually while peering through a little window and looking for the next number. Oh, you've wound on too far, or not far enough? Too bad!

- Comparing like for like, medium-format cameras tend to be bigger and heavier than 35mm cameras.

- Shallow depth of field can be a real headache. If your brain has been trained to think in 35mm terms, a lot less will be in focus at f/11 than you think. If you want frame-filling sharpness then the compromises start to stack up: you'll need to stop down at least one stop, possibly two in 6x9, beyond what you'd need for 35mm. If you're shooting an old camera without a rangefinder or other focusing aid, it can be super hard to actually get anything in focus until your skills catch up.

- Added to this, with many older folding cameras, the lenses simply don't perform 'well' until you close the aperture down. For example, some sources online claim that the Ensign Selfix 420 only gives sharp images to the edge of the frame at f/22. Shooting at f/22 requires either long shutter speeds or lots of light. Maybe both. Either way, you're probably using a tripod.

- Such cameras often lack modern niceties such as double-exposure prevention. This means that, if you're careless, it's really easy to forget to wind on your film before shooting. Or accidentally wind on twice. This means double exposures or skipped frames. This is usually annoying but on rare occasions it can yield unexpected gold.

- Many older cameras were not designed to work with modern high-speed films. For example, the ruby window on the back of many a folding camera will result in light leaks if you stick an ISO 200 or 400 film in the camera. Films of such speed were unheard of in the 1940s, when slow film and contact prints were the norm. Camera shake was far less of an issue for small 1:1 prints, so people often handheld surprisingly slow shutter speeds with acceptable results – but there's nowhere to hide with big prints or modern high-resolution scans on your 27" computer monitor. You'll have to experiment with bodged workarounds involving bits of insulation tape.

- Scanning is potentially more difficult. If you let the lab scan for you, no worries, but if you scan at home then many setups can only deal with 35mm. You might find that you have to upgrade or totally replace your scanning rig when you start shooting medium format (I did – more on this in a future post).

- Storing the negatives requires more physical space.

- The bellows in old cameras often suffer from pinholes or cracks, leading to light leaks. The lens may be out of calibration or not be parallel to the film plane. The lens may be full of crud. Film transport may be dodgy. But file all this under 'ageing diseases affecting many ancient cameras' – medium-format cameras aren't inherently less reliable than 35mm ones, it's just that any 80-year-old machine is going to have issues and will need maintenance.

My journey in medium format

I'll start with a look at the Ensign Selfix 420.

It's a simple folding camera with a 105mm f/4.5 uncoated triplet lens (roughly equivalent to 45mm in full-frame terms). The aperture can stop down to f/22. The shutter offers speeds from 1/150th of a second to Bulb. Focus has ranges marked at infinity, 25ft, 15ft, 10ft, 8ft, 6ft, and 5ft. The shutter has a threaded cable release socket. Internally there's a 6x6 square mask that can be flipped into place before loading. It has two viewfinders: a basic frame finder (with a pop-up square mask for shooting in 6x6 format) and a rotating waist-level brilliant finder that can be used in either landscape or portrait orientation. There's a standard tripod screw on the bottom.

And that's it. No rangefinder, no modern optical viewfinder, no flash sync, no cold shoe, no lens coating, no double-exposure prevention. It was manufactured in 1946 and is the most primitive camera I've ever used – far, far more basic than my Leica IIIc from only two years later. After checking it over to confirm it was in full working condition, I loaded up a roll of Fomapan Classic 100.

The first roll

I'll share my entire first roll from the Ensign Selfix 420, all shot in 6x9 format, along with some notes on each frame depicting this first learning experience. I used an accessory rangefinder to calculate focal distance for some of the shots, guessing for others.

These are low-res exports for the web, but the high-res scans are beautifully crisp and detailed, even filling my entire monitor. I gasped the first time I saw these negatives on the light table.

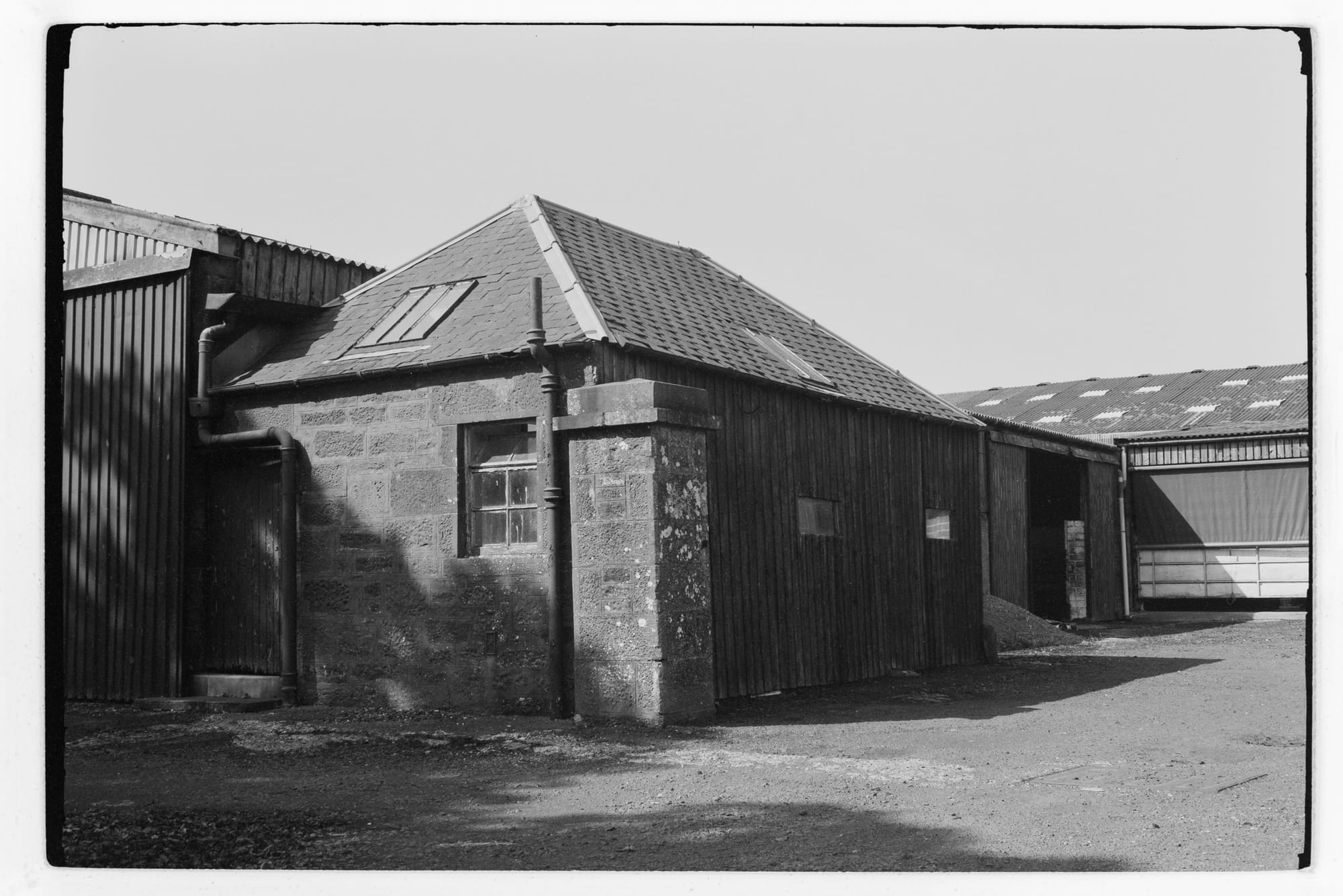

1: Tripod, f/22. Test shot in the yard outside my house. Not exactly level, but the shot is well exposed and sharp, with excellent detail throughout. So far so good.

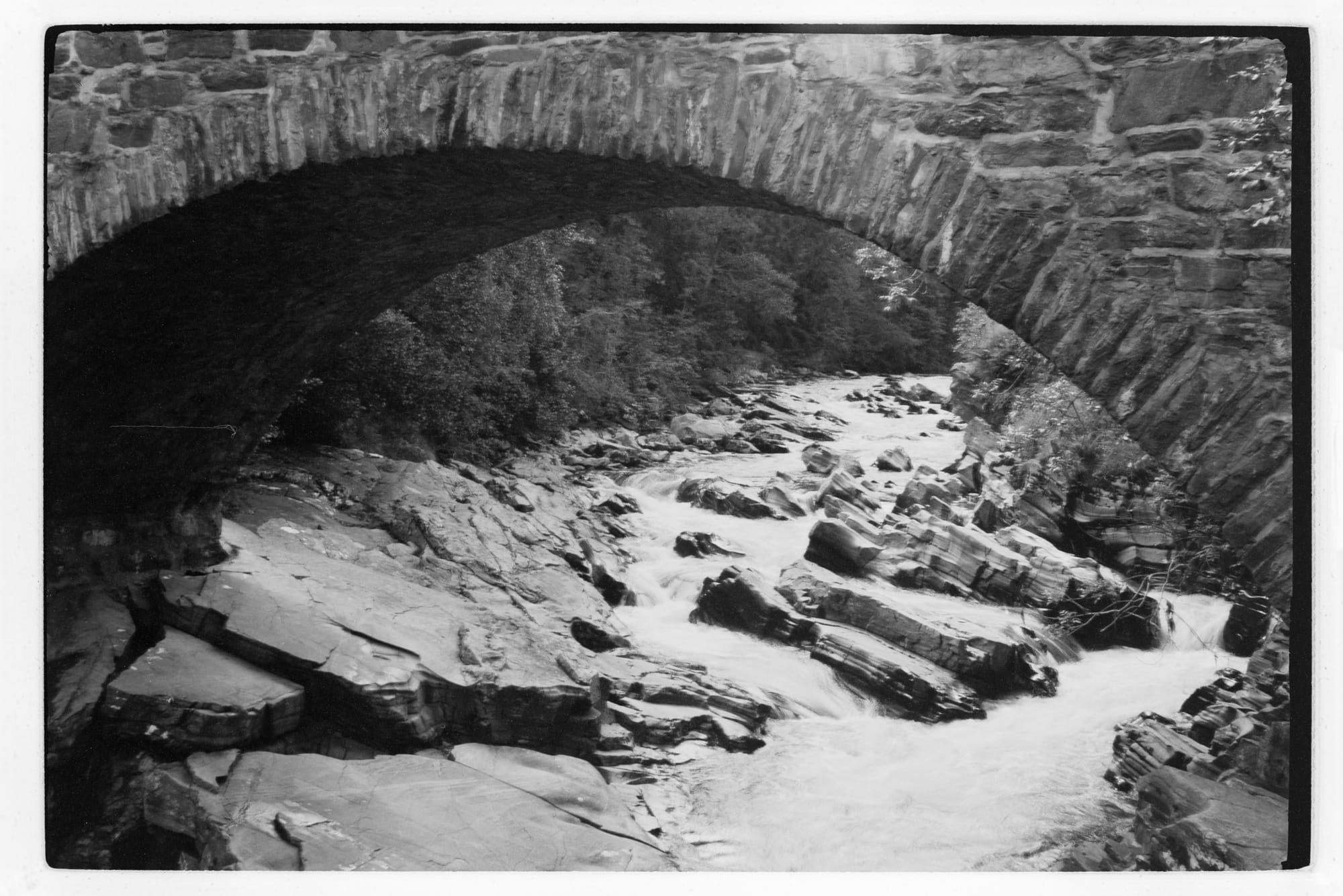

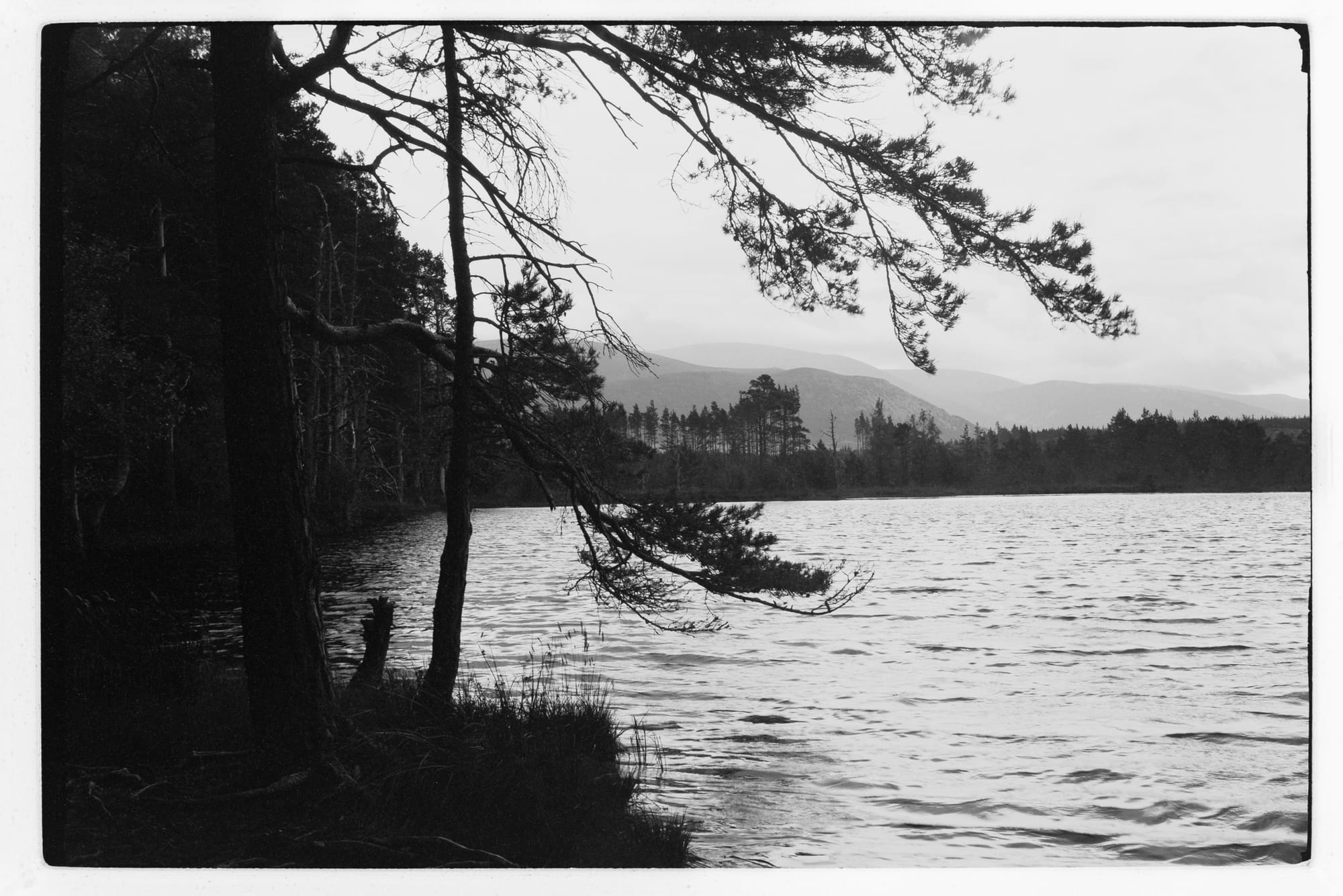

2: Tripod, f/22. First image from an outing in the Cairngorms (the rest of the shots from this roll are from the same day). Despite the camera being mounted on a tripod, strong camera shake is evident; I soon discovered that this camera is really bad at damping vibrations.

3: Tripod, f/22. My first 'proper' image with the camera – a successful landscape detail.

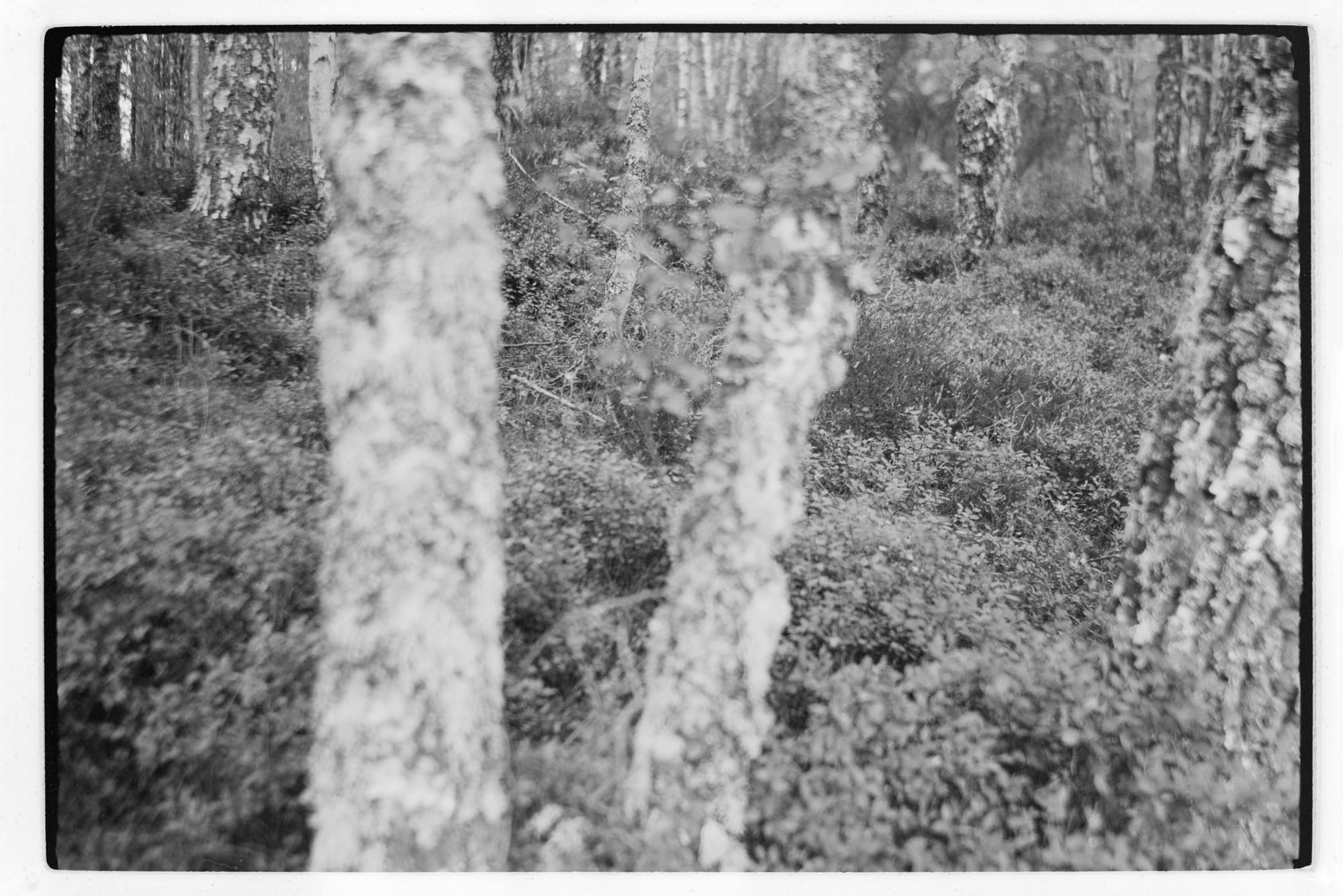

4: Handheld, f/5.6. I was aiming for the trees in the foreground and badly misjudged focal distance.

5: Tripod, f/22. A bit underexposed and wonky horizon, but basically as I visualised it.

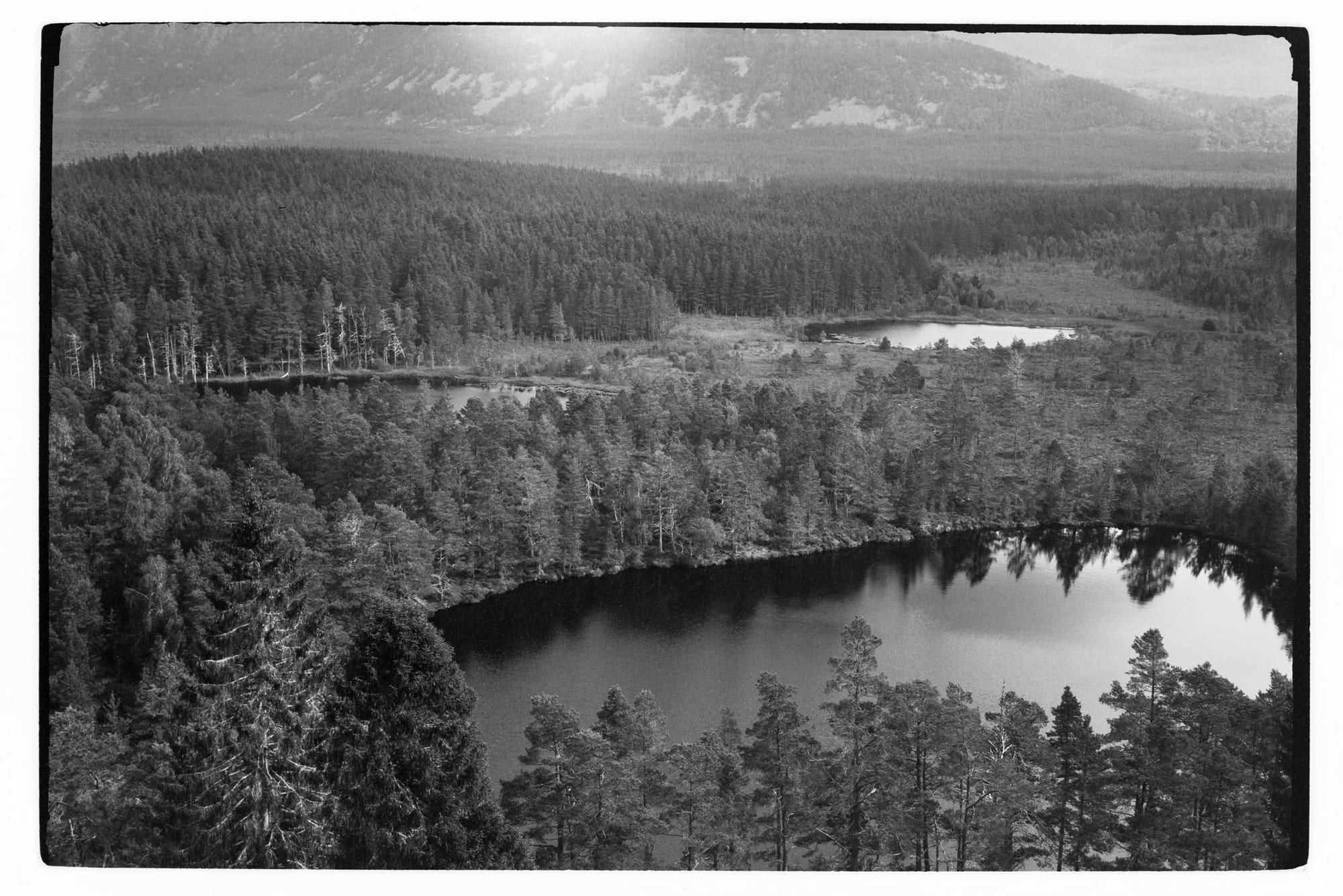

6: Tripod, f/22, from a famous viewpoint above Uath Lochans. I like this! There's a bit of flare in the top of the frame, likely from the bright sky just out of shot.

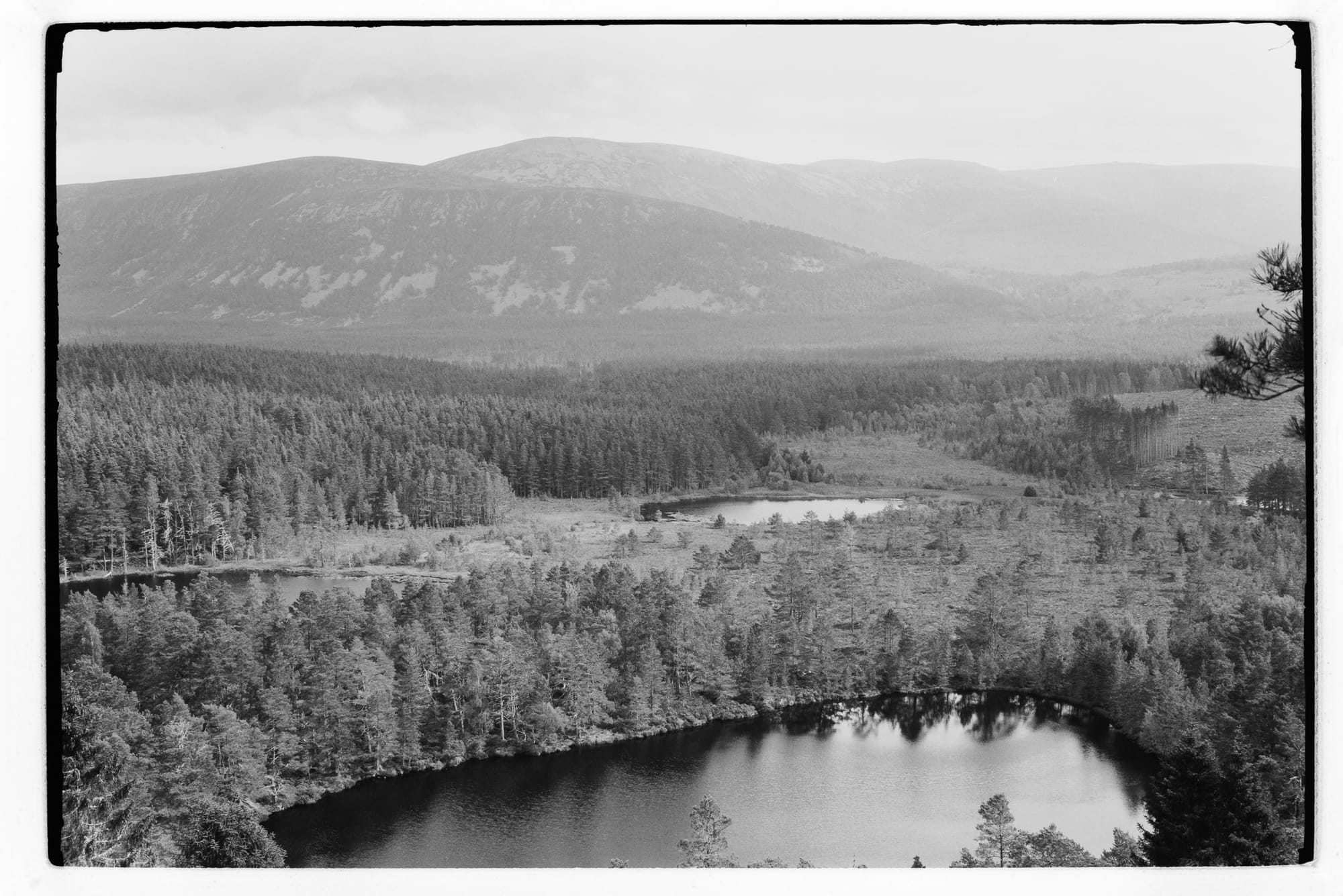

7: Tripod, f/22, same viewpoint. Another reasonably successful image, but here we see the limitations of the imprecise viewfinder. Pointing the camera a bit lower and to the left would have been better.

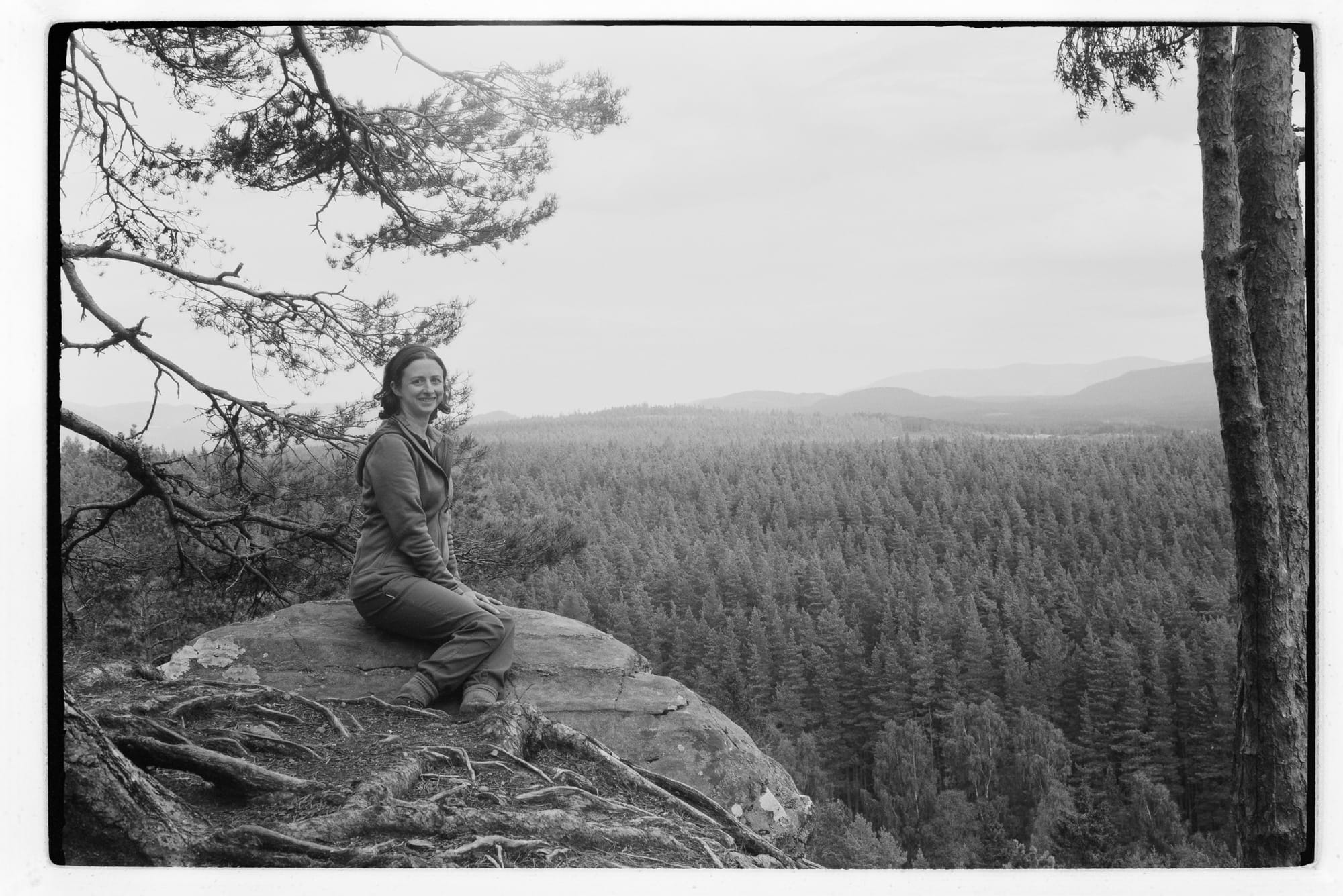

8: Tripod, f/22, same viewpoint. Here my wife Hannah poses for an environmental portrait, and I think the image is a success despite the framing being a bit further to the left than I visualised (I wanted more of the trees to the right in the frame).

I'll finish with a few phone snaps from this little adventure (pictures of me channelling Ansel Adams courtesy of Hannah).

Further images with the Ensign Selfix

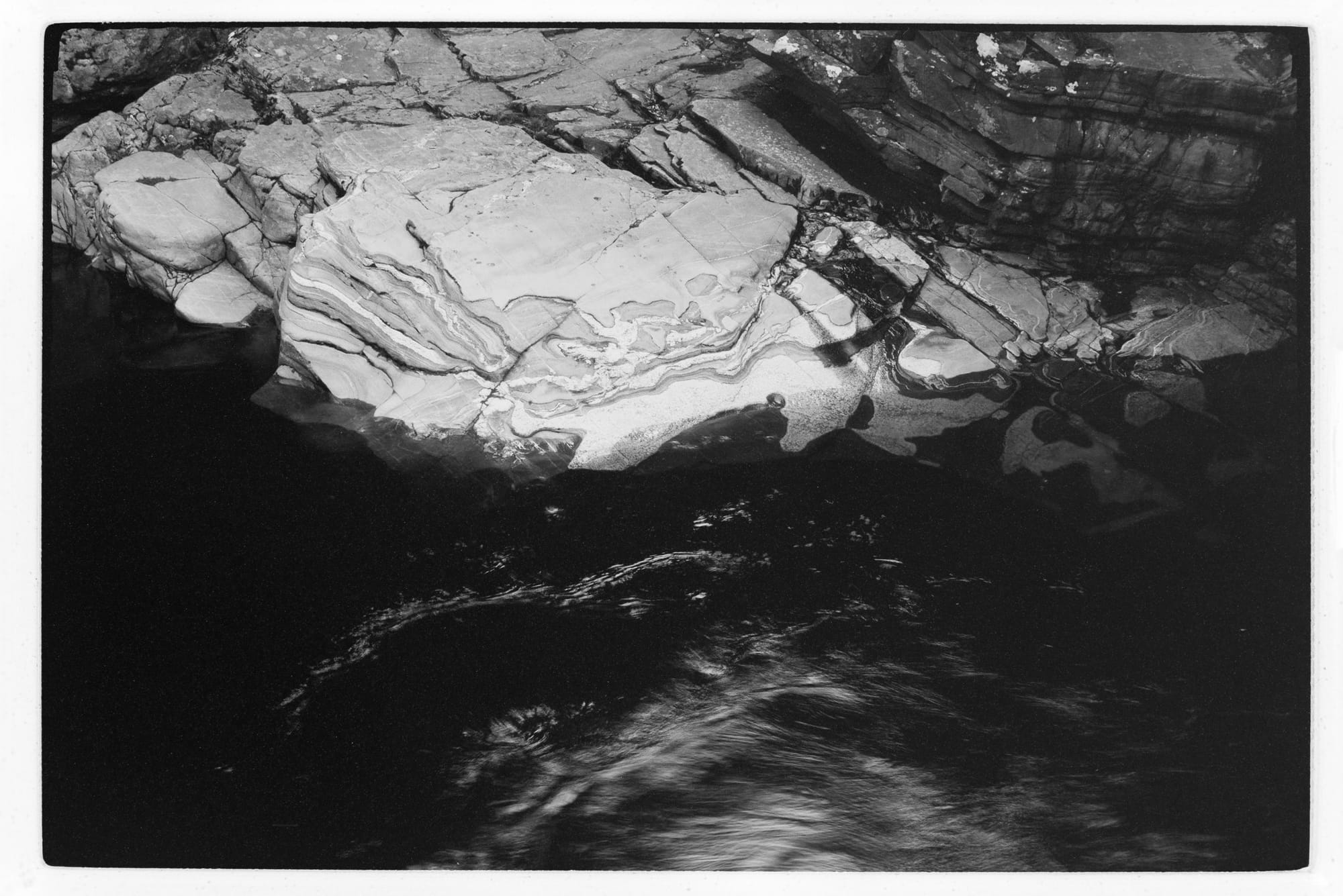

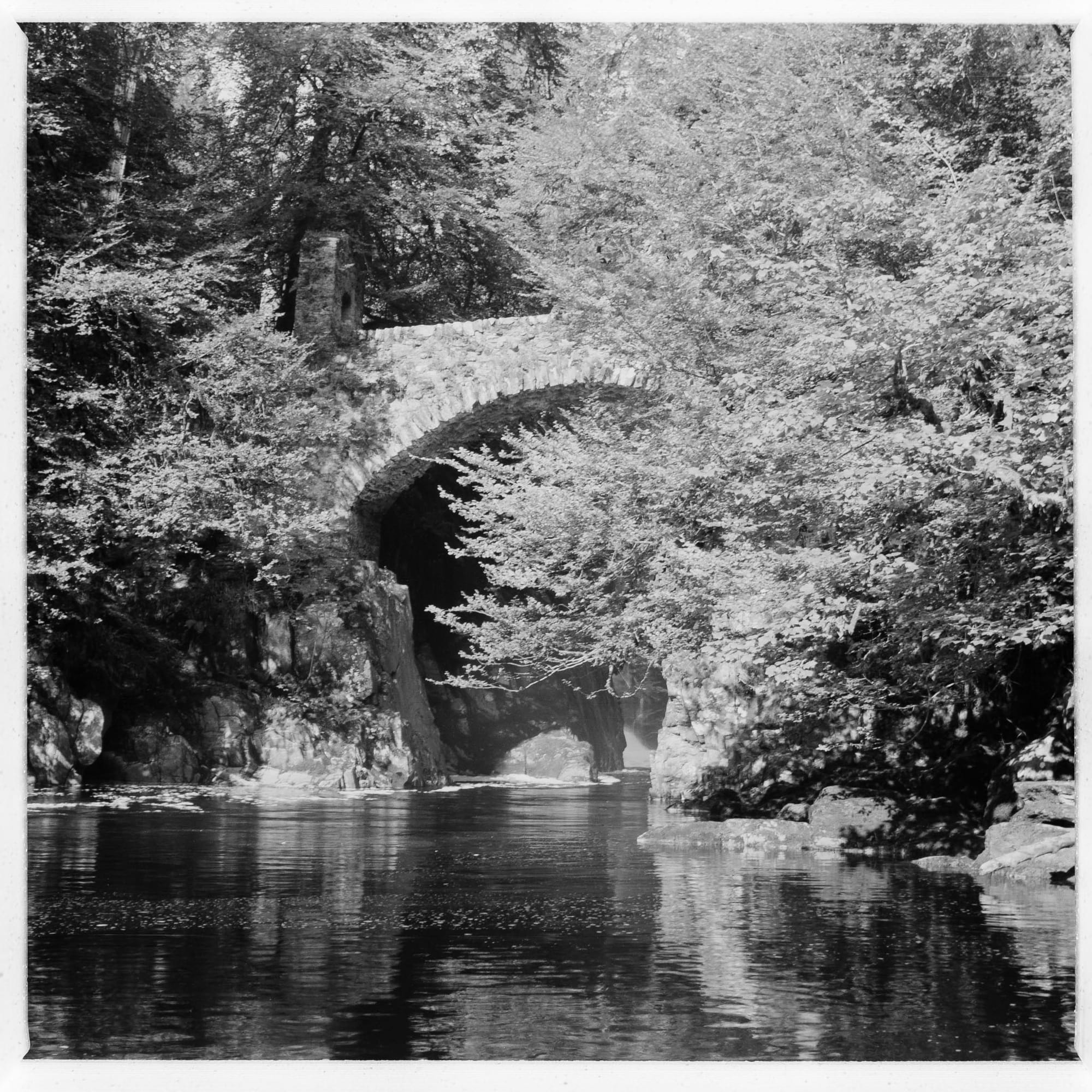

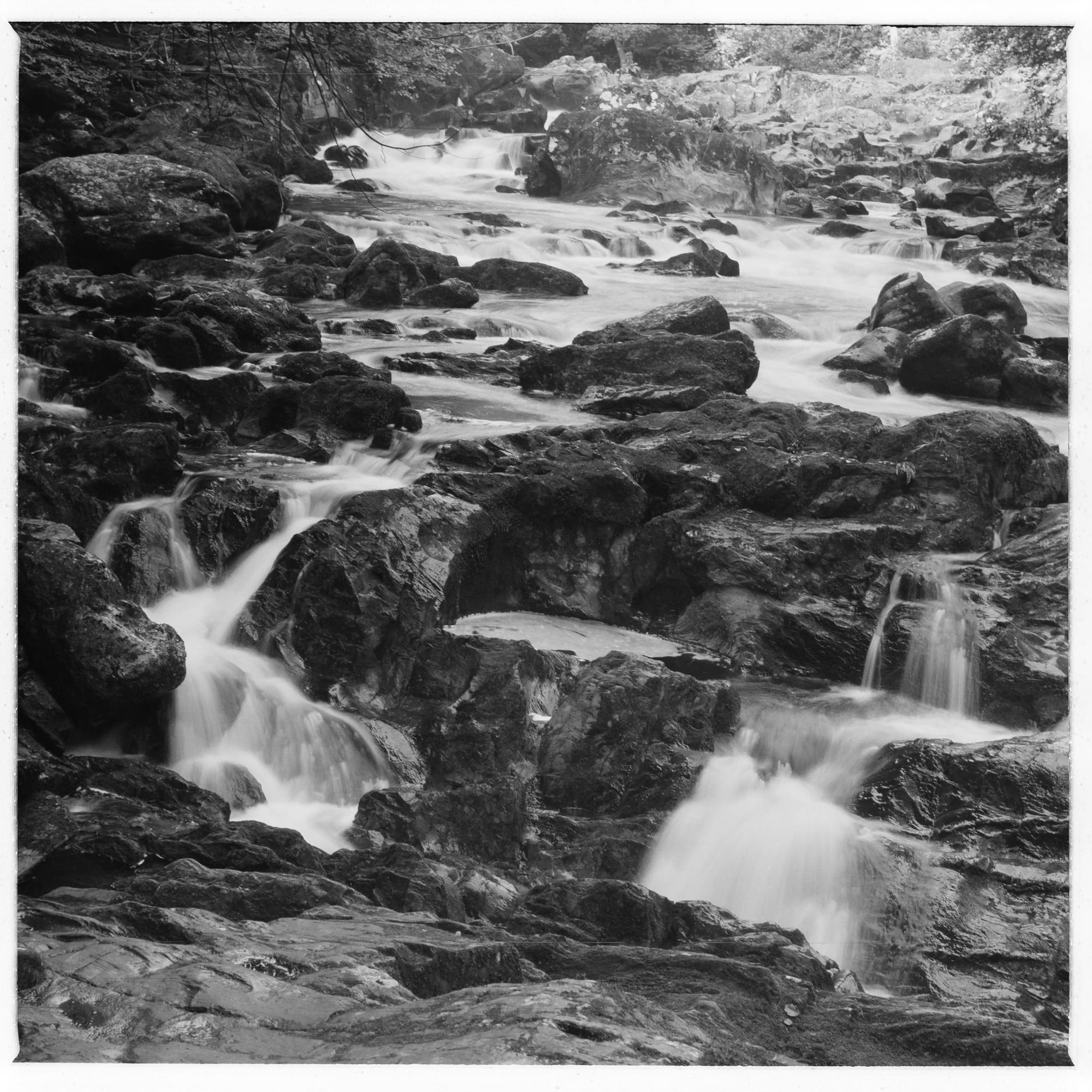

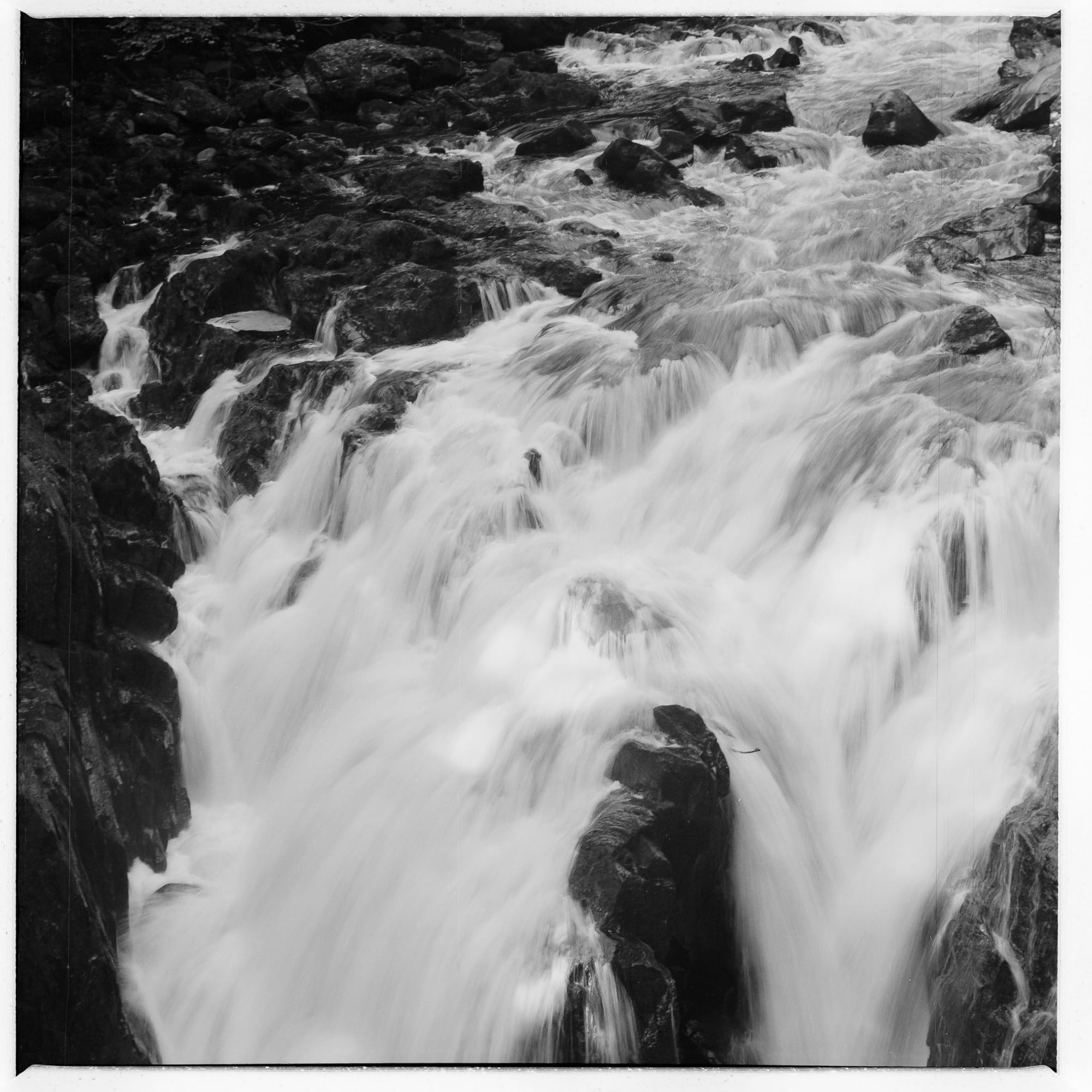

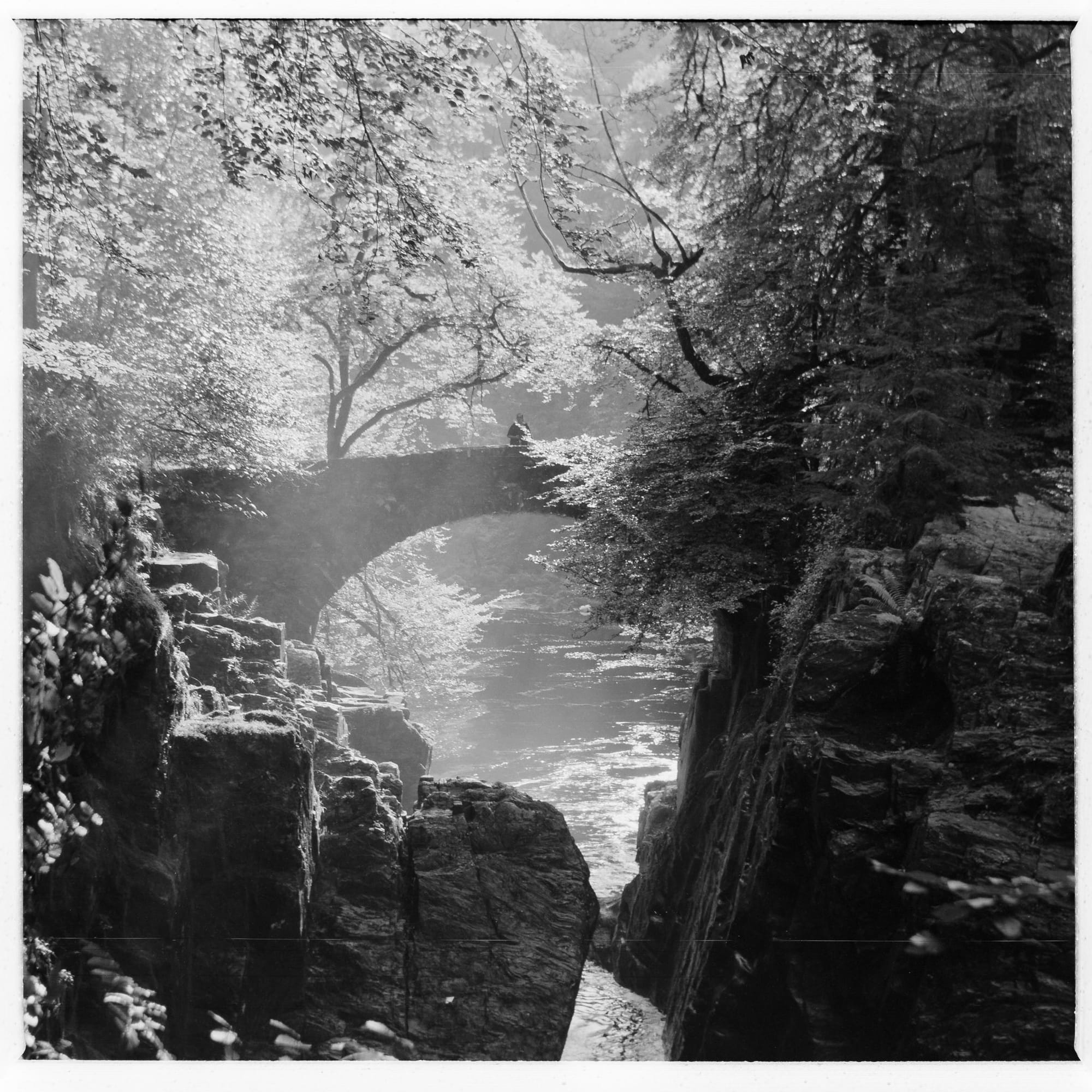

Below I'll share some square 6x6 images I've shot with the Ensign, on a mixture of Fomapan 100 and Kentmere Pan 400. Some handheld, but mostly on tripod. Note the scratches – think there are some sharp edges on the internal mask.

I'm gradually getting the hang of this camera. I've learnt that you pretty much have to use 1/100 shutter speed or faster when shooting handheld, and even then it's 50/50 odds that you'll get some camera shake. I've also learnt that the viewfinders are quite imprecise but seem a bit easier to use in square mode. The brilliant finder is best thought of as a vague approximation of the final image... but neither viewfinder can be used for accurate framing.

It's also easy to forget to wind on to the next frame. I've only made one unintentional double exposure so far, but I have ended up second guessing myself a couple of times. Just something to get used to!

A second camera

Being a sucker for vintage shiny things, it wasn't long before I'd picked up a second camera from eBay. This one is an Agfa Record III from about 1950, and a slightly more modern camera than the Ensign. Just LOOK at those beautiful red bellows. Someone has refurbished this at some point in the last decade or two, and it looks factory fresh.

Like the Ensign, this camera also has a 105mm f/4.5 lens, but it's a more advanced design with four elements and coating to reduce flare. The aperture will stop down to f/32. The shutter offers speeds from 1/500th of a second to Bulb, and has a standard PC sync socket offering flash sync at all speeds. Focus has ranges marked at infinity, 10m, 6m, 4m, 3m, 2.5m, 2m, 1.7m, 1.5m, 1.3m, 1.2m, 1.1m, and 1m. The shutter has a threaded cable release socket on the body. It has a tunnel-type optical viewfinder with built-in uncoupled rangefinder. There's a standard tripod screw on the bottom, a cold shoe on the top, and a depth-of-field calculator next to the shutter release. Finally, double-exposure prevention is present.

It lacks a 6x6 mask and, weirdly, there's no cable release socket on the shutter itself. But my hope was that a much faster minimum shutter speed, combined with a rangefinder and more modern ergonomics (relatively speaking, haha), would make this camera more realistic to shoot handheld.

I've now put several rolls of Kodak Gold through this camera, as well as a roll of Kodak Portra 400, and in most respects it has lived up to my hopes. The Solinar lens creates more detailed negatives at a greater range of apertures than the simpler triplet lens in the Ensign. Basically, image quality is extremely high... but I've been getting camera shake at 1/100th of a second handheld, and even at 1/250th in a couple of cases, which is a surprise as I can usually handhold a Leica with a 50mm lens down to 1/30th or so. But these folding cameras are very light and somewhat front-heavy, and the body shutter release presses a weird series of levers to actually actuate the shutter, which increases the risk of camera shake.

The uncoupled rangefinder is very useful. However, you still have to manually transfer the distance readout to the lens, and it's easy to forget to do this. Something else to get used to.

The double-exposure prevention means no more accidental double exposures... but it's possible to trip this by accident before you intend to expose a frame, and then there's no easy way of firing the shutter (you have to awkwardly press down on a lever tucked behind the bellows). Again, it's just a quirk you have to get used to.

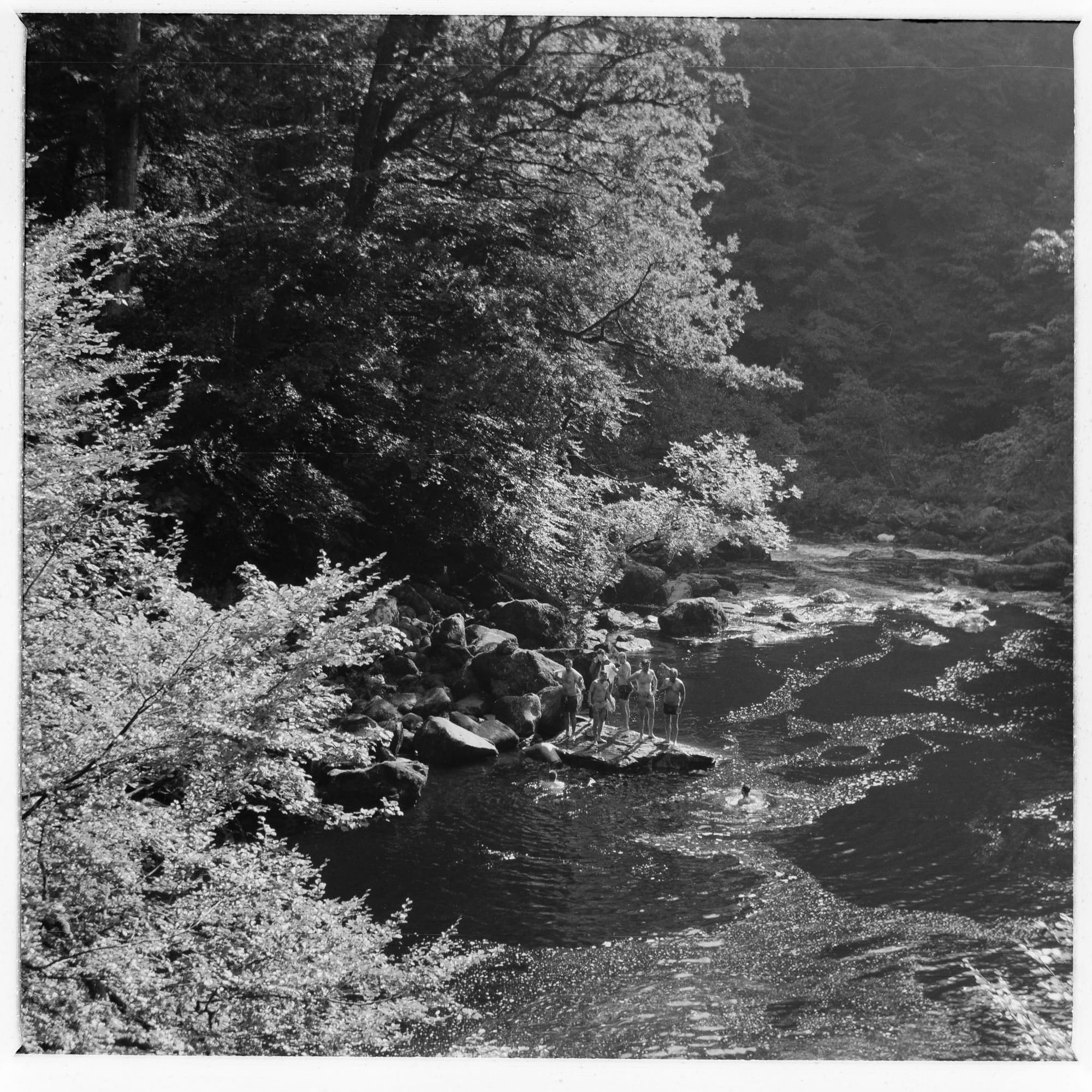

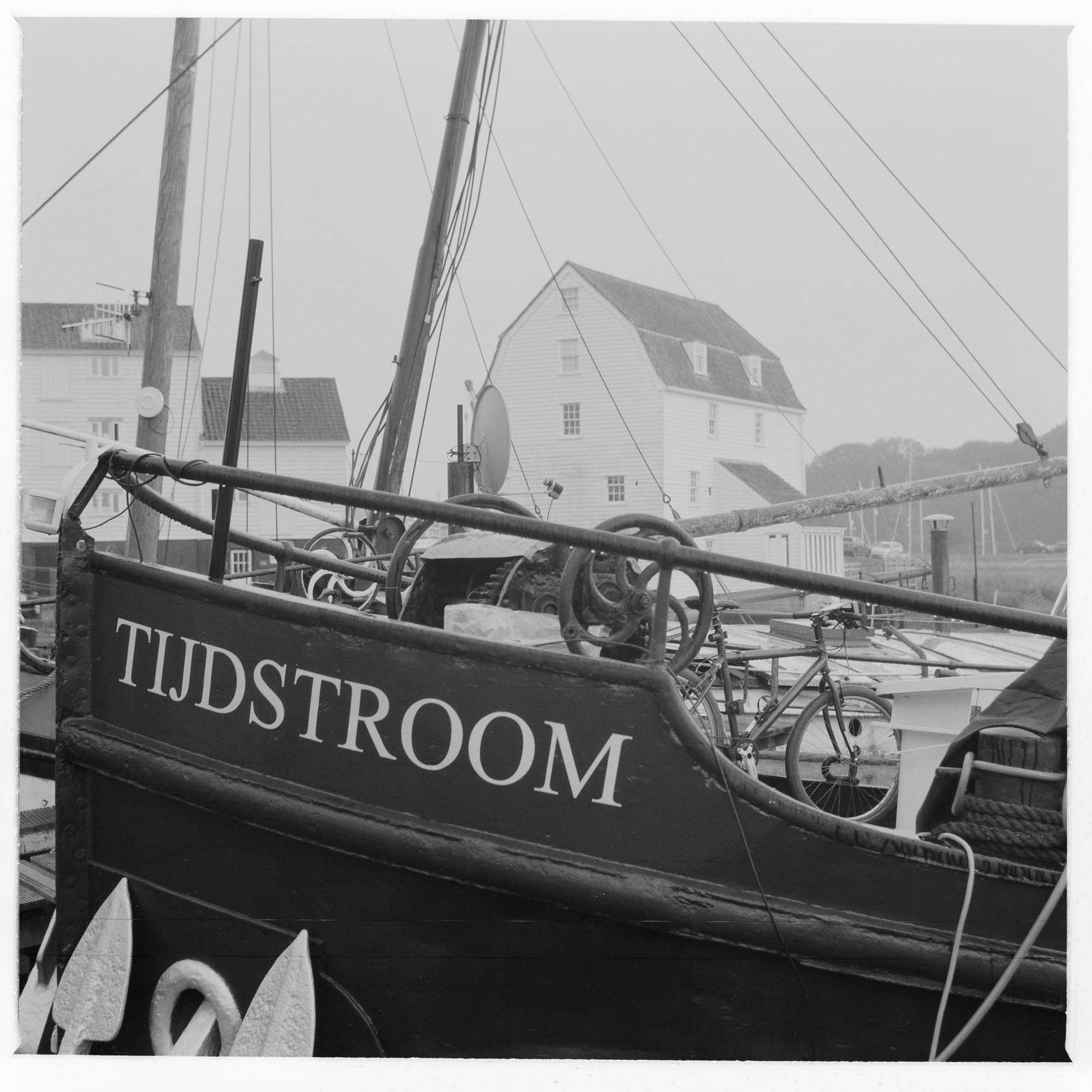

Here are some of my more successful images from the Agfa Record III so far (Kodak Gold and Portra 400).

Final notes

What an exciting learning curve! The images are absolutely gorgeous and, while I certainly don't mind grain in a 35mm image, there's something bewitching about such crisp and clean negatives. Many of them look quite digital in terms of detail, but with the analogue colours that digital can't replicate (and, of course, the distinctive rendering signature of simple vintage lenses). Combine that with an even more slow and intentional process than 35mm and you have a highly rewarding formula.

But both cameras have some pretty significant quirks – some inherent to the format, some to these cameras. There's no way I'd ever consider switching 100% to medium format. Even if I could afford something like a Pentax 6x7. And, honestly, once I've had my fun there's a high chance that these cameras will return to the camera cabinet and remain there except for specific assignments or the odd outing. They're never going to be workhorse cameras for me like the Leica M3 is.

Shooting with these ancient folders makes you really appreciate what an advance the Leica and its cousins were for photographers. Coupled rangefinder making focusing easy, a film advance that both cocks the shutter and winds on film while preventing double exposure, film in a protective canister, and an automatic frame counter you can see at a glance... marvels of convenience that everyone takes for granted today, even on what we now regard as fully manual 35mm cameras, but take them away and perhaps you get a step closer back to the true essentials of photography.

Of course, if that's what you're seeking, the true endgame is large format. But that's a step too far for me. We've all got to pick our own preferred balance of art and convenience, and that's what makes all this so fun.

My scanning rig

One final comment about the scanning rig I've used to digitise these negatives. I won't go into detail on this here, because it could be the subject of an article itself, but in brief I decided to build a DSLR scanning rig based on a Nikon D800 with 60mm f/2.8 macro lens, a home-made copy stand, a Cinestill CS-Lite light source, and a Lobster Holder for securing the negative. It can handle both 35mm and medium format up to 6x9 and is a big step up in quality and speed from my previous setup. I use Lightroom and Negative Lab Pro to convert the DNG files from the Nikon D800.

All images © Alex Roddie. All Rights Reserved. Please don’t reproduce these images without permission.

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Subscribe here to receive my occasional personal newsletter in your inbox. (For the fun stuff, please consider subscribing to Alpenglow Journal instead!)