Something in the darkness to believe in

A moment that exists outside of time, a crucible of community in the mountains, and new human perspectives on moral dilemmas

Backpackers have a saying: 'the trail provides'. In other words, life on foot has a way of giving you exactly what you need, which is not necessarily what you want.

Over the last couple of weeks, I've been gradually piecing together a no-holds barred treatise for this blog on why I can no longer morally justify posting on Instagram. As I write this, the draft is more than 6,000 words long. It is, I believe, well researched and argued. I've sent it to a few friends to ask their opinions on it, and I've incorporated their remarks. One advised me to keep it back for a chapter in my next book, or to refine it and pitch it to the Guardian.

At the core of my argument is the fact that Mark Zuckerberg has become increasingly brazen about his desire to train Meta's AI systems on Instagram content – a fact that I find abhorrent. This triggered a moral crisis in me that led to a complete halt in my Instagram activity. However, it isn't a simple situation.

One thing I knew: that I'd need to wait until after the Kendal Mountain Festival. Because I always talk to so many people at Kendal, take in new (or just alternative) ideas. I knew that conversations about social media would happen. And I didn't want to jump the gun by posting my essay – an act which is going to feel like throwing a hand grenade into a crowded room and running away – before having those conversations.

So I waited. I'm glad I did.

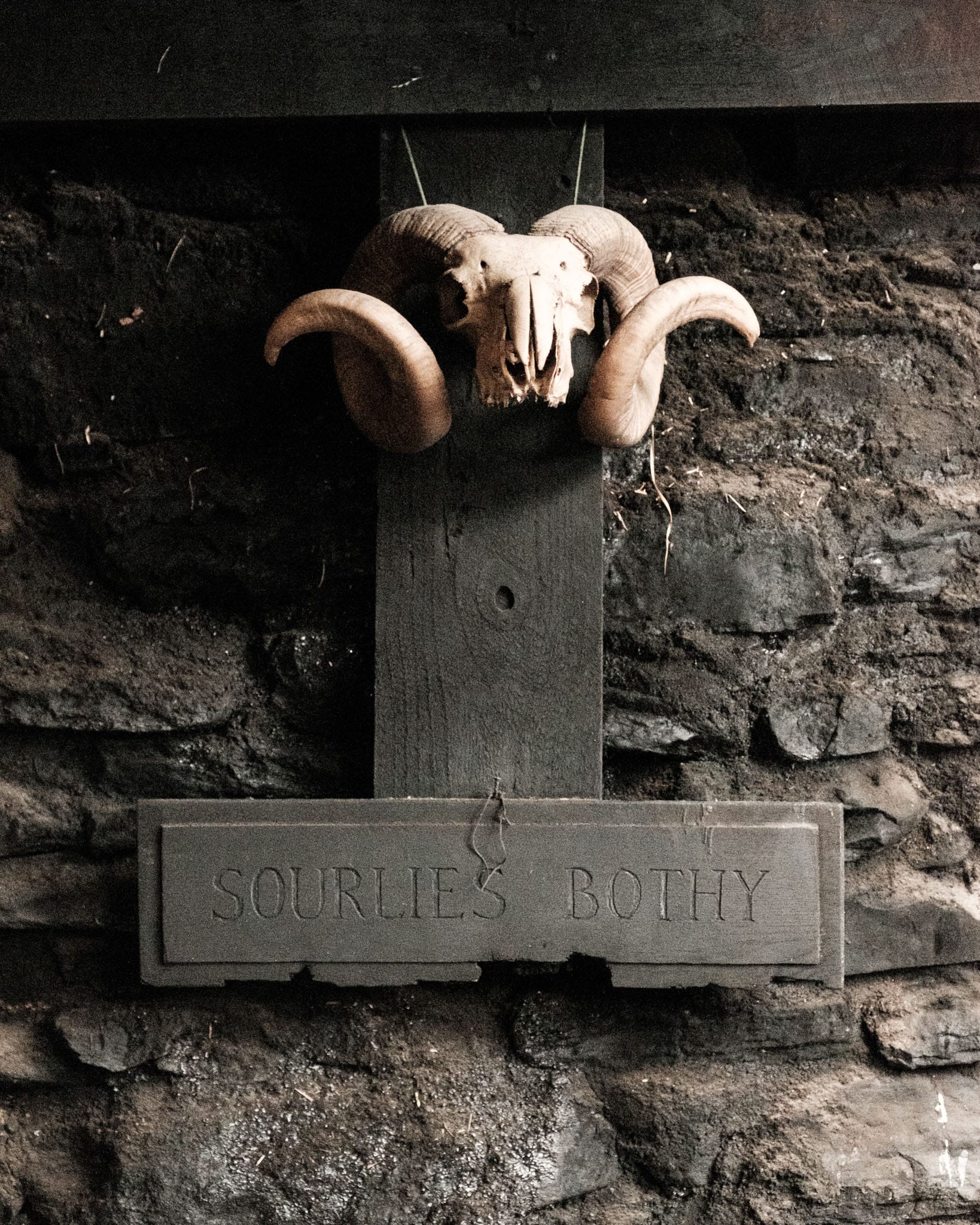

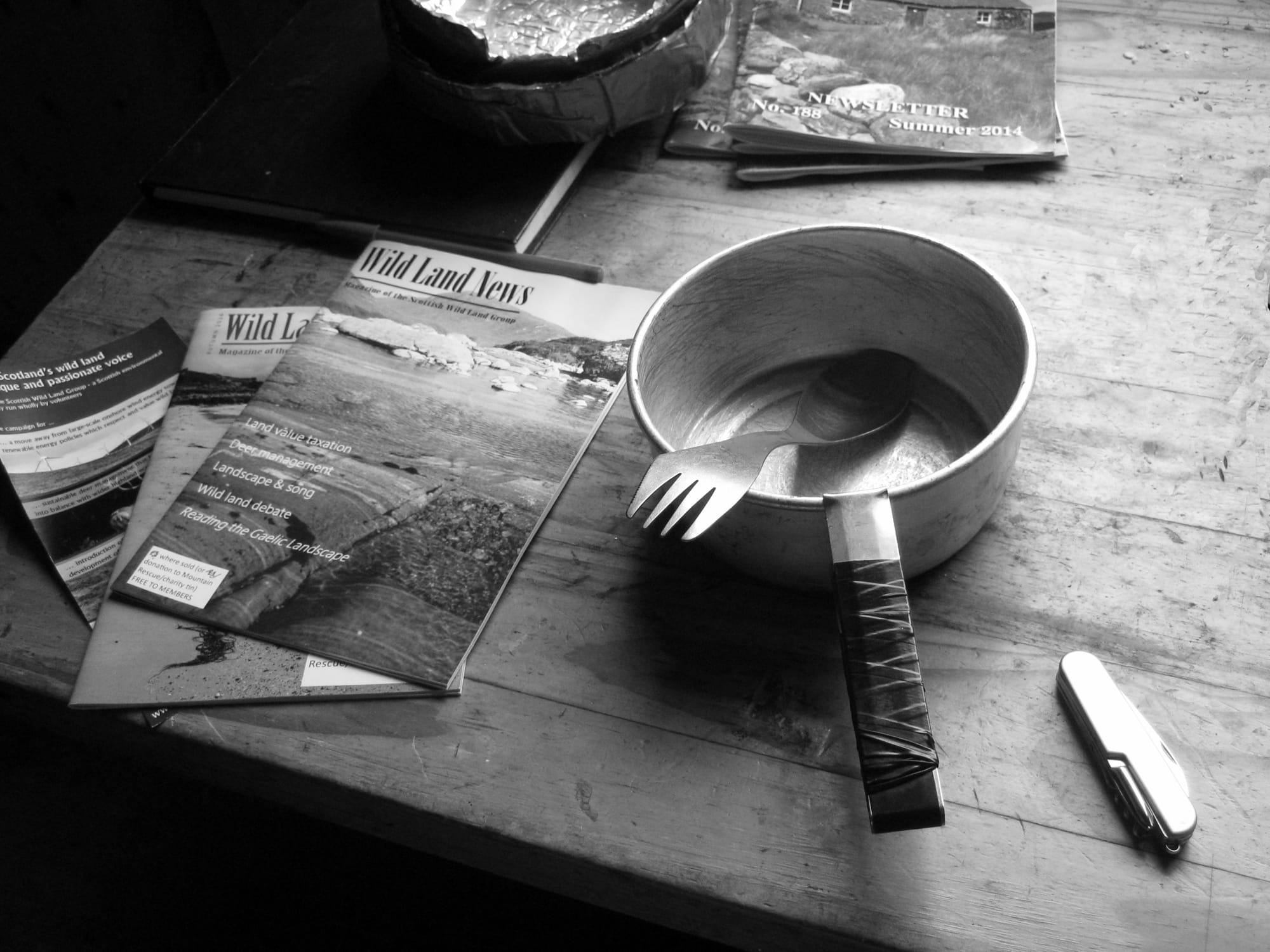

On Thursday night, my friend Andy Wasley and I began the steep haul uphill in the dark from Haweswater to Mosedale Cottage – one of only a handful of bothies in the Lake District. In case you aren't familiar with the concept, a bothy is a basic shelter in remote mountain country, free for all to use as long as a few basic rules are followed. Bothies tend to be primitive, with no facilities such as electricity or running water or plumbing.

The idea was for a social bothy evening before the craziness of the mountain festival began. So we hiked uphill in the freezing night air, rucksacks laden down with wood to fuel the bothy fire and whisky to fuel the bothy craic. Our headlamps remained off for as long as possible. The switchback trail beneath our feet revealed itself as a glimmering suggestion in the veiled light of moon and stars. Then we hit an engorged ice slick and switched lamps on for safety.

The bothy greeted us, as so many bothies do, only at the last possible moment as we came around the corner of a scrap of forestry. The rectangle of a single window was suspended there before us, aglow with the promise of fire and candlelight and companionship.

This moment exists outside of time.

For as long as humans have built dwellings it has been thus: the bright portal painted against the night, reached only when bodies are tired and aching for rest and wondering if journey's end will ever come. The moment when shelter becomes real. The moment when when? becomes now.

In a very tangible sense, I believe that in this moment we relive the same fixed point in the lives of countless thousands of individuals, stretching back into deep time. Before, perhaps, there were buildings at all – just the glowing mouth of a cave. Something in the darkness to believe in.

In living that moment again and again, we remember – and we affirm our humanity. It is the simplest thing there is. A fundamental atom of experience: just us, the light, and the cave. Nothing can be more analogue. Nothing can be more human.

But communion with deep time collapses back into the particulars of the present day when we step over the threshold. Voices always hail a welcome, but each time the welcome is different. There's the warmth of a bothy fire, or perhaps the frigid chill of a stove without fuel; condensation on spectacles, or maybe snow goggles; the curiously disappointing realisation that light comes from cold electric lamps as well as candles. Stepping over the threshold is different each and every time.

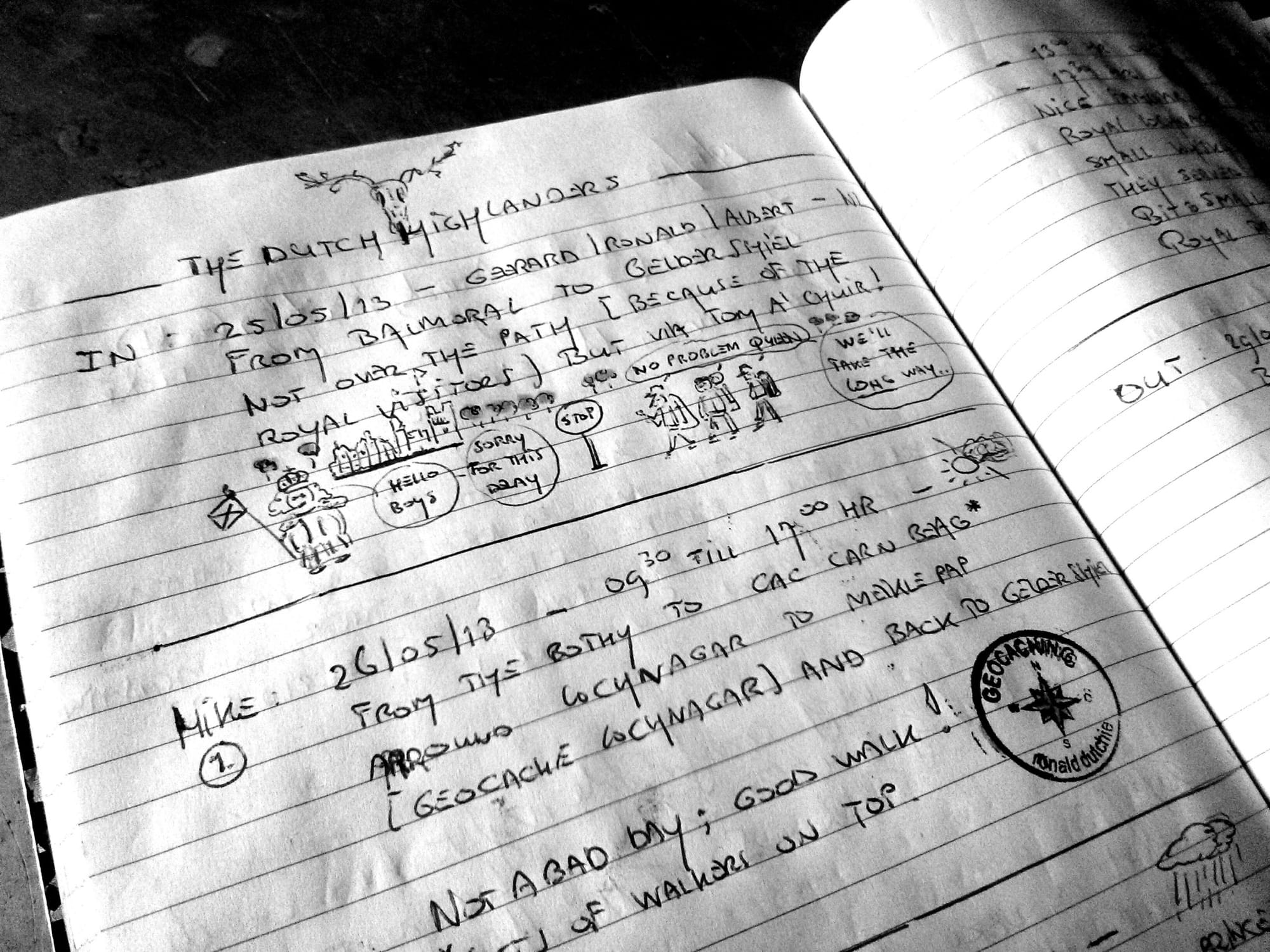

One thing is pretty much always true, though: people make friends instantly in bothies, these special worlds that exist just a bit apart from everywhere else. That night those present in Mosedale Cottage included Juls Stodel, the woman who has visited more bothies than most people living. Her adventures are the stuff of legend in long-distance hiking circles. Name the trail, and she's hiked it; name the bothy, and she knows it well, and most likely has an outlandish story or two about it to pass on. Also present was Jess Day, communications specialist for Right to Roam. Like her friend Juls, she had also hiked the Cape Wrath Trail – which made four of us, including me and Andy. Finally, Juls's friend Sam had interesting stories of his own as a groundsman for a Buckinghamshire estate, as well as his hiking adventures.

Moments from Mosedale Cottage

Our wood bolstered the fire, and we were all soon deep in conversation and laughter. Whisky was passed around. Eventually, the chat moved to social media, and I mentioned some of my moral problems with Instagram. I said I was sitting on a draft blog post about being unable to justify participating any more.

The others said they understood my dilemma, but for them Instagram was a place of friendship and community. Jess told me that after she moved to a new town and dived headlong into hiking and the outdoors, Instagram was how she found her tribe, made new friends – including Juls – and filled her life with meaning. Her real life, that is, beyond the feed. Meanwhile, Juls told me how great Instagram had been for sharing her amazing stories from the big bothy walk. And, it has got to be said, it was through Instagram that I first began to follow her stories. She uses this platform in a very genuine and human way: connection and community beyond the feeds, bringing people together in real life.

Meanwhile, I reflected on my friendship with Andy. We've known each other offline for a few years now, but it was Twitter, that wretched black hole of woe, that first brought us together. And it was through Instagram that Andy messaged Juls to ask if she fancied meeting us at Mosedale Cottage and bringing some friends.

I left Mosedale Cottage the next morning grateful for these new friends, grateful for their perspectives.

There's a kind of solace, for me, in Luddism. I've studied it for so many years now – read so many books, filled so many notebooks, refined my views as I get ever closer to something like a unified theory of analogue counterculture and the imperative of resistance against the machine. I study the politics, ethics and philosophy; I immerse myself in the arguments of academics, whistleblowers, scientists, writers and artists.

When I write with authority and passion on breaking machines and holding onto our humanity while embedded in platforms with hostile goals that do not align with our own, it feels good. It feels right in a way I find hard to explain, as if this philosophy has a rightful place, an obvious place, in the narrative of my life. And I believe it does! I became a Luddite when I studied computing science at university almost 20 years ago; I just didn't know it back then. The richest, most rewarding journeys I've ever done have been undertaken with these philosophies at the front of my mind. There is a powerful personal story here for me. I believe in it.

Bothy moments from my 2019 winter Cape Wrath Trail: a journey when I learned much about analogue counterculture in adventure

And yet.

I think endlessly about how to retain our vanishing humanity, but my fellow humans can still surprise me. Despite everything, despite the many evils of technofeudalism and surveillance capitalism, despite the idea that we are serfs in the fields of attention technology, people are fighting the system right now without even knowing it. People are retaining their humanity – celebrating it – in a system designed to turn them into machines. People are using Instagram for connection, friendship and community despite the fact that it is using and changing us all, despite the ulterior motives of the platform.

And maybe, I find myself thinking, that's OK. Or at least you can argue it's OK. Maybe if we can use the system for these fiercely good ends it doesn't matter so much what it wants from us, what it does to us. At least sometimes. Maybe it's valid to ask if a system that can enhance our humanity even as it tries to degrade us is worth saving. So let's ask that question! I don't have an answer. But I want to have that chat around a bothy fire with you. I don't want to lecture about a position I've come to on my own by reading books and writing essays. I want to talk about this face to face, human being to human being. This, my friends, is how we resist – by having that conversation out there in meatspace.

I was all set to state my position that we have a moral duty to break this machine, to take our communities and friendships somewhere less thoroughly compromised. A very good case can be made for that argument, backed up by decades of work from far deeper thinkers than me. But I keep having to be reminded of the human factor, and the irony of this isn't lost on me.

In The Matrix, one of the greatest Luddite movies of all time, Morpheus said: 'Many of these people are not ready to be unplugged. And many of them are so inured, so hopelessly dependent on the system, that they will fight to protect it.'

I used to think this was a statement of moral authority – that Morpheus knows something these poor jacked-in suckers don't. But there are multiple interpretations here, aren't there? I mean, this is a whole movie of multiple interpretations. Leave the Matrix and you may achieve your moral purity, but at what dreadful cost? Not only are you hunted by the machine, you are now an enemy of the vast majority of humans as well. In reaching for a pure ideal of humanity you have dehumanised yourself.

Cypher (the Judas figure in The Matrix) is portrayed as the villain for preferring the Matrix to the 'desert of the real', and to be fair he does some pretty vile things in service of the machine. But, questionable choices with directed energy weapons aside, I think his fundamental decision – to stay jacked in – should be considered with more compassion than the movie affords him. However, when The Matrix was created in the 1990s we did not actually live in a cyberpunk dystopia, and people had not considered these moral choices in their own lives. The situation in 2024 is very different. Hashtag cyberpunk is now.

Look, I don't want to be too dramatic here – I'm not seriously arguing that Instagram is the same as the Matrix, a system of physical servitude to an omnipotent AI, albeit fictional. But let me run with a metaphor, OK? Let me have my little moment of moral purity before I dive back into the nuances of it all!

Perhaps fighting for a system that gives you friendship, community and meaning is more rational than fighting against the abstract machine, even if that would be the morally superior thing to do. I don't always get this, but right now, in the days after our evening at Mosedale Cottage, I do get it.

I don't have any answers. Sorry. I've been searching for answers for nearly 20 years, but I don't think I'll ever find them. Only more questions, and maybe that's how it should be.

I can say this. I'm not going to publish my 'let's blow up Instagram' essay. At least not yet. I will take more time to reflect and gather views – real human views, not just the published words of philosophers. I keep having to relearn this lesson, it seems. If and when I publish, it must embrace the human side of the dilemma.

For now, I'm still stepping off Instagram, but that's because I'm not sure, and I think that'll always be better than being sure. About anything. I do want to break machines, but I want to know what I'm breaking before I raise the hammer.

I keep coming back to the image of that moment beyond space and time: the candlelit bothy window suspended against a field of stars in the endless night, approached by the traveller. This most human of things, this symbol in the darkness to believe in, can never be appropriated by the machine – and yet is it a coincidence that Instagram presents itself as a grid of these illuminated rectangles on a background of black?

Friends, it's all entangled. But let's stay human. And remember: the machine is much, but it is not everything.

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Subscribe here to receive my occasional personal newsletter in your inbox. (For the fun stuff, please consider subscribing to Alpenglow Journal instead!)