Looking for a rural sense of place in dead week

What makes a place a place, what happens when we lose it, and can we get it back?

It's the dead week between Christmas and New Year, and Hannah and I are back down south in Lincolnshire spending time with family and friends. In many ways I love this time of year. It's a week I always take off work, and as we're pretty much always down south with family, mountains aren't on the cards. This means that dead week is exclusively about rest – unlike any other time of the year, such as holidays, which usually involve mountains (and therefore stuff like goals and planning, which are fun and necessary but don't really count as rest).

This week, Hannah and I have been watching old movies, reading books, seeing friends, going for walks. I've exposed more rolls of film than I planned, and the images are all of things I've photographed umpteen times before, but that's ok. It's a week of rest. No pressure.

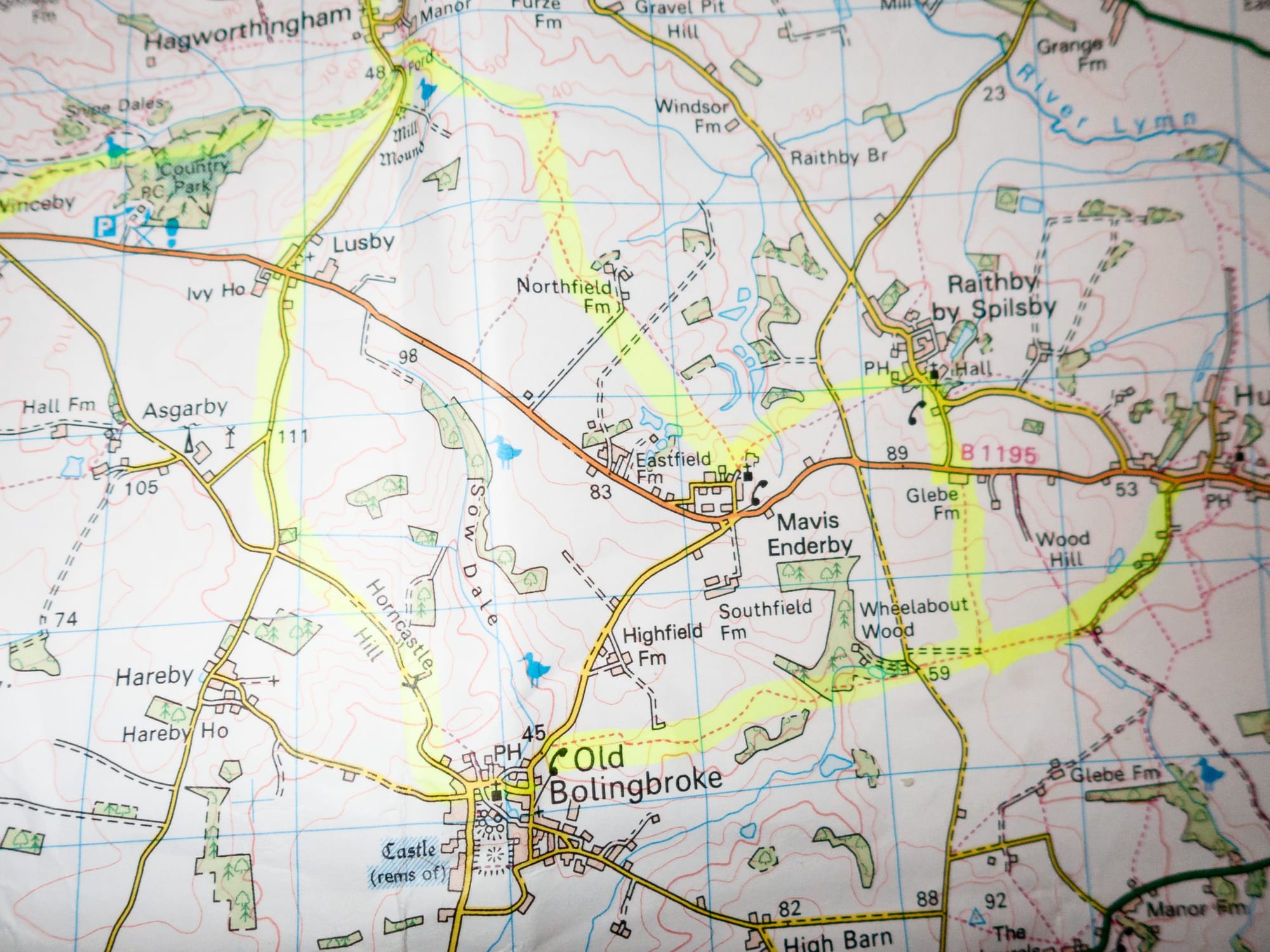

On Sunday, after days of thick fog finally lifted, I wanted to take myself off for a long solo hike in the Wolds. One of my favourite walks in the area is a circuit from Hagworthingham taking in Mavis Enderby, Raithby, and Old Bolingbroke. It's a walk I've done many times over the last 14 years, summer and winter, and I always enjoy it. I mean that without a trace of irony. Those who wink and say, 'Awfully flat in Lincolnshire, eh? A long way away from the mountains!' are dramatically missing the point. As I wrote in 'Last months in Lincolnshire' back in 2022, 'I have learned more about my relationship with mountains by living in Lincolnshire than I ever did when I lived in the mountains.'

It's taken me a long time to realise this, but what I really crave when I go for a walk is to engage with a sense of place. You don't have to go to the mountains to find that. But places are delicate, and can easily be damaged or destroyed.

The village of Old Bolingbroke is clustered around the ruins of a castle that was destroyed during a siege in the English Civil War. A bewildering maze of narrow lanes surrounds the castle like a spider's web, hemmed in by old cottages whose gardens hum with bees and butterflies in the summer.

I first visited Old Bolingbroke in 2010 with Hannah. It was our first date, and our walk took in the ruins of Bolingbroke Castle. We sat on a bench and ate our sandwiches, throwing crusts to the ducks. Since then we've returned as a couple several times, but I've probably come back more often on solo walks. And those walks usually involve a pint of Batemans XB at the Black Horse Inn.

You aren't really supposed to climb about on the castle walls, but we did anyway. These images are from 2014-2022

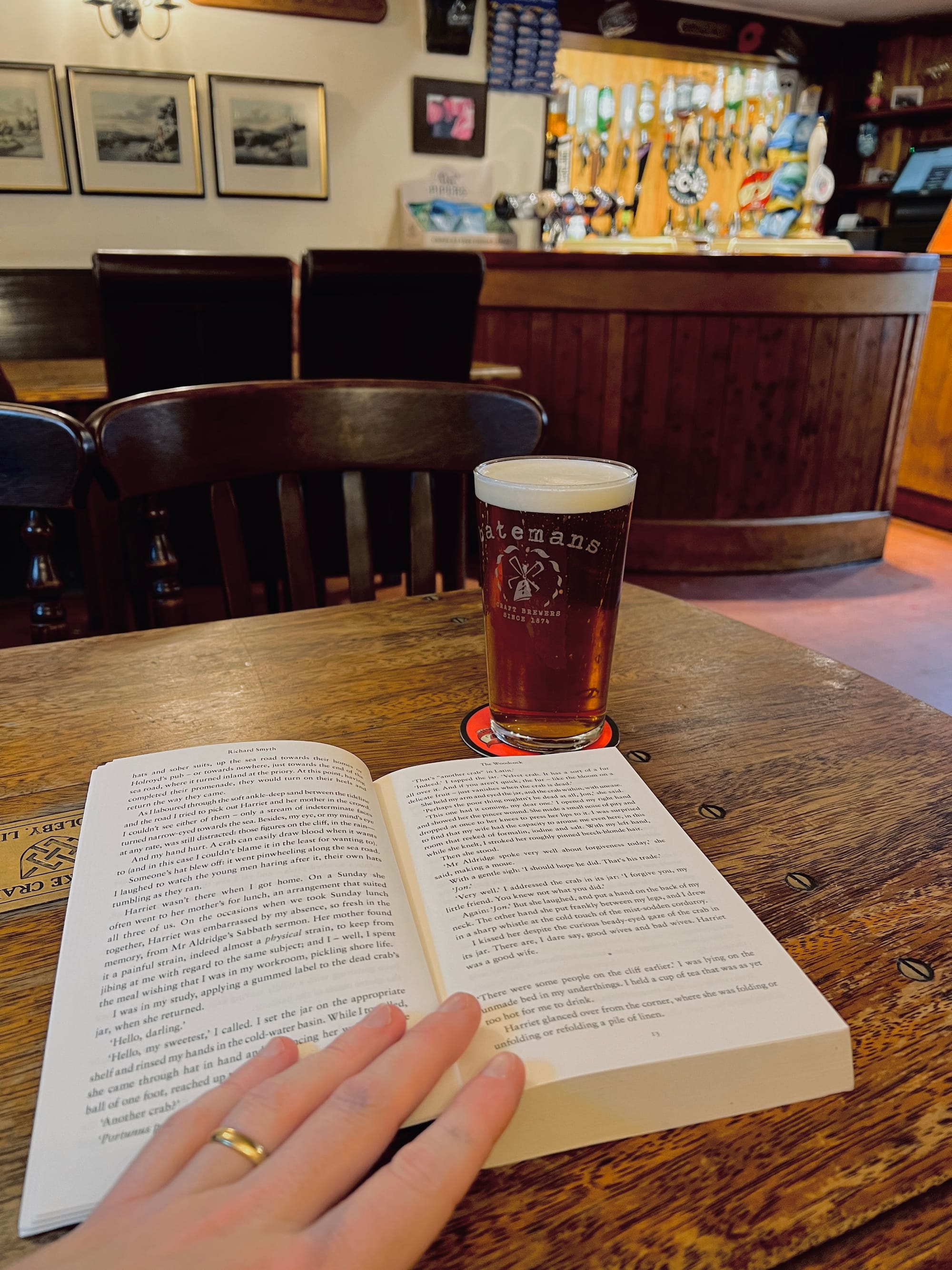

The Black Horse always matched my mental picture of a proper rural pub. Well-kept beer, a roaring fire, time-worn wooden furniture, and no loud music. No traffic noise either, because there aren't many cars here. Just birdsong. I always used to enjoy my chats with the landlord – although I never asked him his name, and that's something I regret now.

I remember one visit in 2017. After taking the first sip of my beer, I settled down at my table and took out my camera, then swapped in a fresh roll of film. The landlord caught my eye and told me how delighted he was to see a 'youngster' using a vintage film camera (nowhere near as common pre-pandemic as it is now). We chatted for a bit, and then he ducked behind the bar for a moment before returning with a box of his old camera gear to show me – plus some photos of fast cars from the 70s or 80s. He told me that in his past career he'd been a professional motorsports photographer.

For me, this is what makes a place a place: the human connection.

So, back to my dead week walk planning. I looked at my map, traced the highlighted line around the Old Bolingbroke route, and thought, yep, time for that walk again. But I also realised it might be a good idea to check the pub's opening hours, being a Sunday between Christmas and New Year.

I soon found a notice on the WhatPub website that described the Black Horse as 'long-term closed'. Then I found a link to a news story from October, describing the villagers' battle to save their last pub.

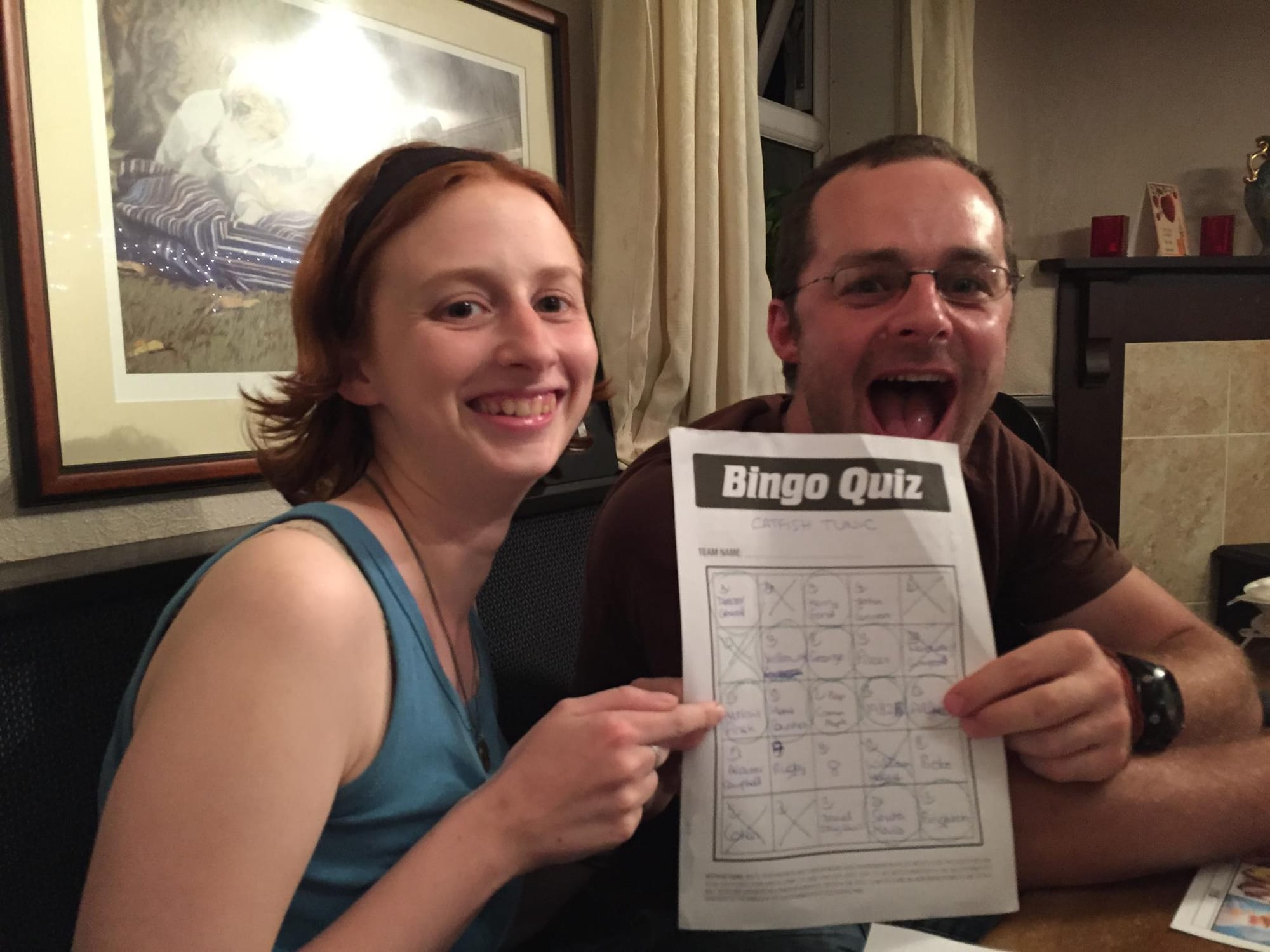

Disappointed by this news, I ended up doing a different walk instead, and had my pint next to the fire in the Blacksmiths Arms, Skendleby. Another favourite local pub – and another one with strong personal connections. For a couple of years about a decade ago, Hannah and I used to head there every week for the pub quiz with our friends Steve and Chris.

Hannah and Steve celebrating a particularly impressive pub quiz performance at the Blacksmiths Arms in August 2015, and enjoying a solo pint and a book on a walk a few years later

I enjoyed my hike, but it was tinged with a sense of unease and disquiet. At the fragility of place, and of rural life itself. I joke that I'm a country bumpkin at heart, but why make light of a deep-seated love of rural living? Rural places are always more real to me than urban ones. I've lived in villages for most of my life. Yet everywhere I look I see villages being hollowed out, changed into retreats for urban people who are seeking an escape. From what I can only guess. Are they reaching out for some form of community they feel they can't find in the city? Do they just want some peace and quiet? Do they yearn for a 'simpler life' in the countryside? I can't be too harsh, because I feel it too – that nostalgia for a more grounded way of life I have never known, that 'fluttering emotion' I wrote about in 2019 in 'Went to mow the meadow'. The destruction of rural places goes back a long way.

I'm not saying this kind of urbanisation is what's happening to Old Bolingbroke, the village that once had three pubs and now has none. But maybe it's part of the same overall trend, packaged up with rural depopulation and delocalisation. Villages become enclaves of the city. And bit by bit, with every church that loses its roof, every village hall that closes because not enough people use it any more, every family that moves away, every pub that becomes a house and every house that becomes an Airbnb, places lose their distinctiveness.

But gloomy ruminations can never last long, because if there's one thing humans are good at it's continually making those connections and relationships – the things that make places real. And we'll continue doing this even when our public spaces are taken away from us. Even a village that has been reduced to no more than a dead cluster of holiday cottages still has much: trees that watch over our conversations, sunsets to be enjoyed on an evening walk with a loved one, deer to be pointed out to a nature-curious child. And a place remains a place while there are memories to sustain it.

That said, I live in hope that a rural renaissance is possible in Britain – an end to delocalisation and urbanisation, and a return to real places with strong communities based around shared traditions, shared goals, shared struggles. Not just ghostly outposts of city life. It seems like a lot to pin on the humble village pub, but maybe the rot has got to stop somewhere.

How can visitors help? Treating villages with respect is a good start. Be quiet and courteous, take litter home, and don't treat the place like a theme park (I've seen tourists taking pictures through the windows of cottages before). Support local businesses! I'm not just talking about pubs, but also cafes, independent shops, and small village stores. Don't just buy in your supplies from the big Tesco in town. Tourism is a vital part of the rural economy and we can all do our bit to be good tourists.

What of Old Bolingbroke's future? From the BBC article about the fate of the Black Horse:

Earlier this year, the parish council applied for an ACV, but was turned down by East Lindsey District Council on the grounds that there was "no clear evidenced use of this premises as a public house since 2012".

However, a recent survey found 89% of villagers who took part were likely to support a community-owned pub.

Ms Powell said the parish council was now considering a second application.

So perhaps there is hope for this Lincolnshire village yet.

All images © Alex Roddie. Images produced using a camera and free of AI contamination. All Rights Reserved. Please don’t reproduce these images without permission.

Are you receiving two copies of my posts in your inbox? You might be subscribed on both alexroddie.com and Substack. Here's a FAQ with instructions on what to do.

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Subscribe here to receive my occasional personal newsletter in your inbox. (For the fun stuff, please consider subscribing to Alpenglow Journal instead!)