Freezeframe – one last journey into the Cairngorms before the world changed

Five years ago, with the first Covid lockdown imminent and a perfect forecast, I decided to seize the opportunity to complete a long-dreamed-of Cairngorms traverse in perfect winter conditions...

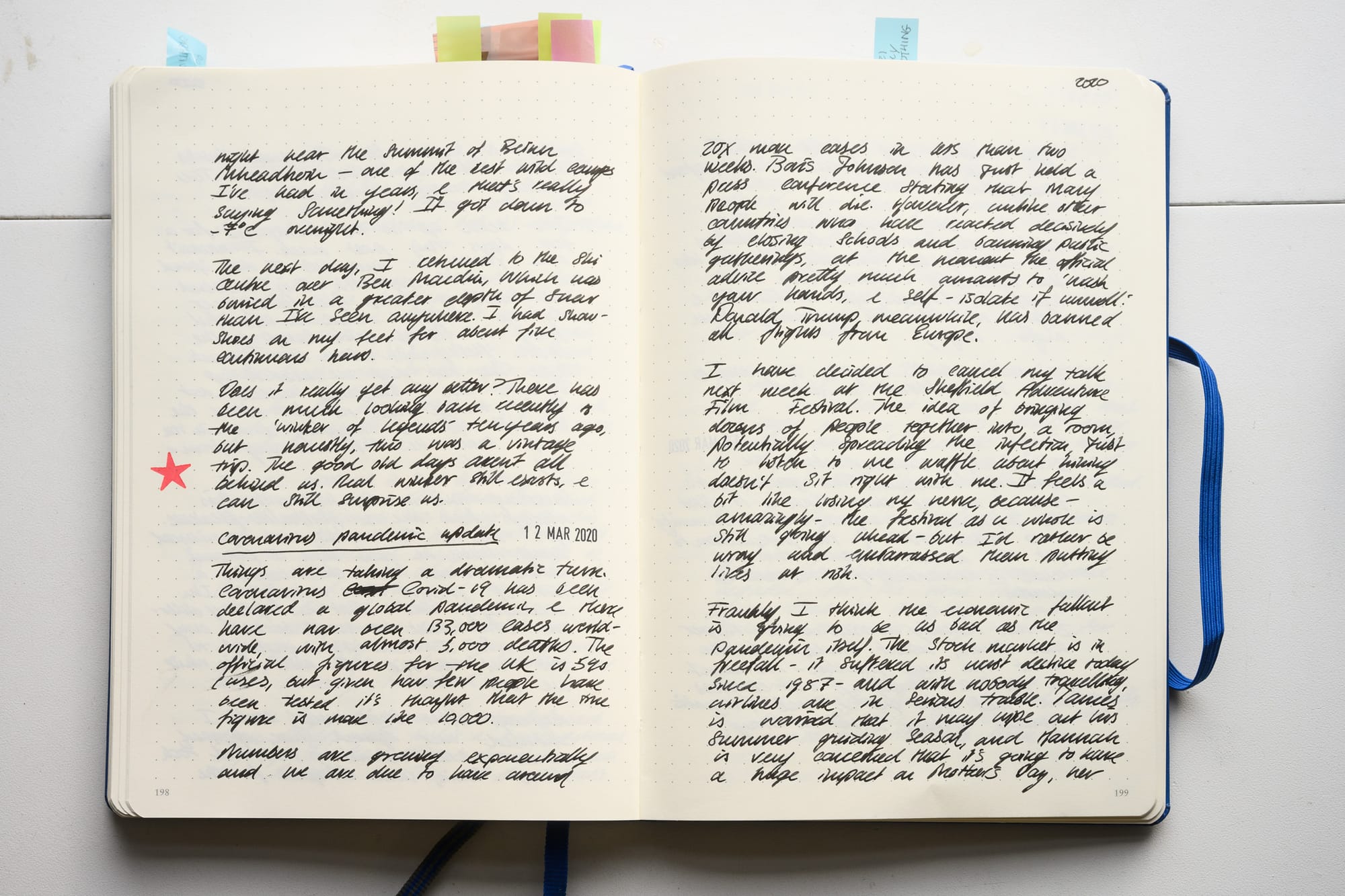

There was a sense, that week, of the world drawing in on itself. The headlines were full of apocalyptic warnings as the number of daily COVID-19 cases in the UK crept up from one or two to ten or twelve. I don’t think anyone could predict just how much our lives would change in a short period of time, but I felt one thing powerfully, instinctively: while it lasts, enjoy the freedom you have now.

I felt the pull of wide landscapes and vast skies. As I traced ridgelines on maps and studied guidebooks I realised that I’d already planned the perfect itinerary. Back in February 2015, I’d arrived in Aviemore to find the Northern Cairngorms blanketed in deep snow. Even walking up through Rothiemurchus was a struggle. By the time I reached the little gear shop at Glenmore, I realised that without snowshoes I’d be going nowhere; fortunately they had a pair of inexpensive plastic ones they didn’t mind selling to me. After a night at Ryvoan bothy, I struggled to the summit of Bynack More the next day in atrocious weather, fighting my way through thigh-deep drifts, and decided to turn back before it got any worse. My ambition for a multi-summit winter tour of the Loch A’an Basin would have to wait. And wait it did – for five years.

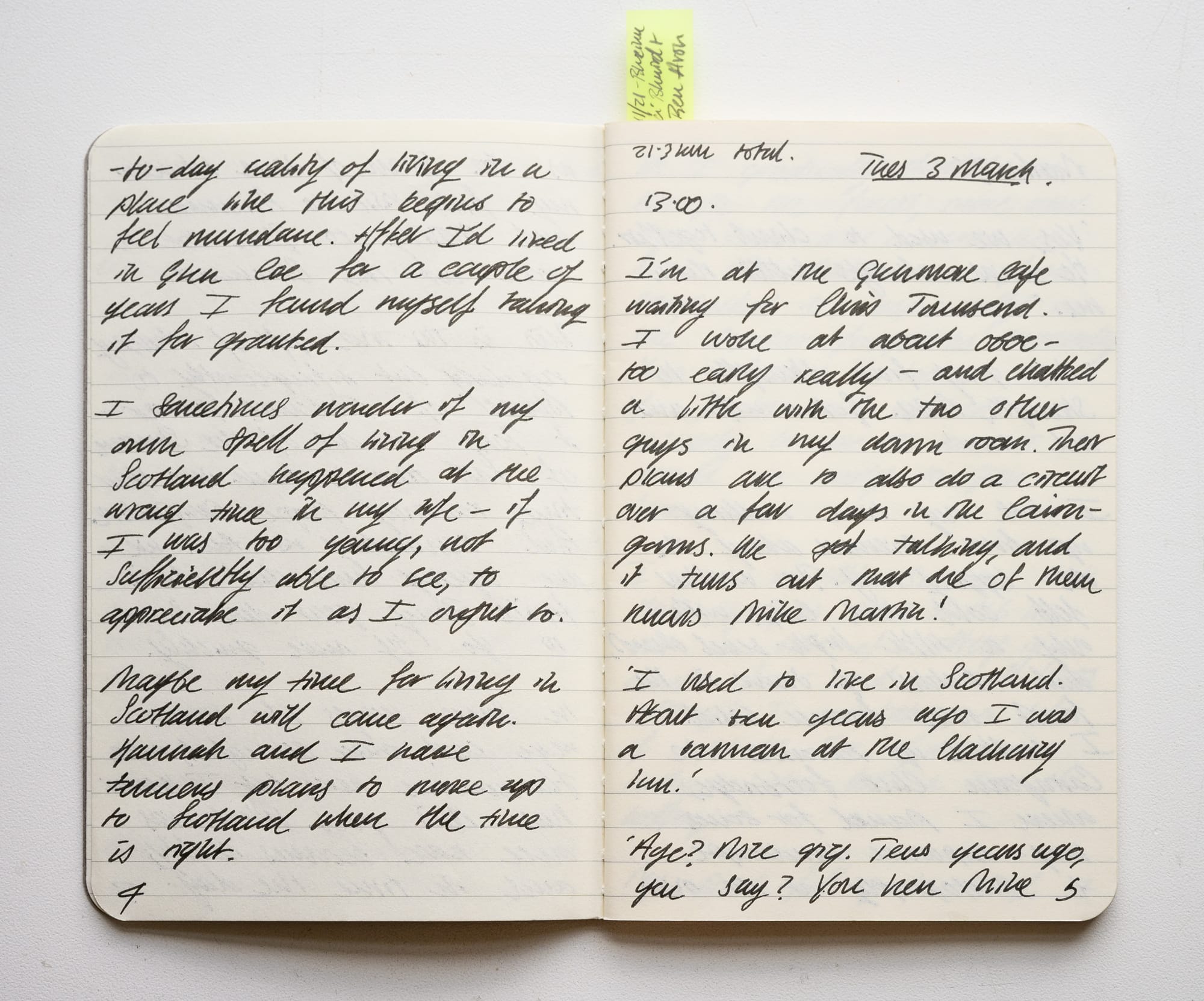

As lockdown loomed, I knew that the time was right to return and have another go. It felt more urgent than any trip I’d planned in years. This time the weather would be on my side, and I dropped TGO’s Chris Townsend a line to see if he fancied joining me for part of the journey. “Sounds great,” Chris replied. “Let’s meet up at Glenmore and head over Ryvoan Pass.”

Although it’s easy to get a bus as far as Glenmore, I’d rather take my time and walk up through the forest, which is what I did on a bright and sunny morning in the first week of March 2020. Snow banks piled up by the sides of the paths glistened in the sunshine, while the paths themselves had been packed down by countless boots and then refrozen hard into a glassy patina of ice. The air felt calm but with a delicious bite. I crunched through the woods, letting my gaze drift unfocused through the wall of trees ahead of me.

Chris met me at the cafe in Glenmore. As we discussed plans over an unfolded map my excitement began to mount. “The forecast’s great for the next couple of days,” Chris said, and he nodded at the snowshoes strapped to my rucksack. “Snow cover is great on the plateau too. I think you’ll get some use out of those.” He’d packed snowshoes as well. As a relative newbie to this subtle winter art I was looking forward to picking up a few tips from the master.

We ambled slowly up through the forest towards An Lochan Uaine (the Green Lochan) and Ryvoan Pass, just above the treeline. This is a magical place where the interplay of forest, moorland, water and mountain creates something greater than the sum of its parts – a place of intricacies and ever-changing complex detail. The young trees seemed to have leapt upwards by a foot or more since my last visit. When Chris and I found a spot to camp next to the River Nethy with a view over to Bynack More, I remarked that the rowan saplings on the other side of the river seemed taller than I remembered. “They are,” he said. “I remember when there were no young trees here at all. This place is changing fast.”

Our camping spot seemed no more than functional at first, but it soon grew on me. Chris and I pitched our tents a few metres apart, choosing pitches with sparser snow cover than the rapidly refreezing blanket coating the heather on all sides. More snow had come down as we were setting up camp and I assumed it would be an evening sealed up inside silnylon and down, listening to the patter of snowflakes on the flysheet. But when I pulled on boots to collect water I found that the sky had cleared and moonlight streamed down on a landscape of breathtaking beauty and softness. We spent a while looking at the stars, and gazing up at the brow of the mountain we planned to climb the next day, and watching the water flow past quiet and deep in the river below: simple things, yet precious beyond price.

Bynack More is one of the easiest Munros to climb in the Northern Cairngorms, but it isn’t easy. Four years earlier I’d felt exposed and insecure on the steep summit ridge in storm-force winds and driving snow; this morning could hardly have felt more different. After waking to the blush of alpenglow and taking a leisurely breakfast, we began the walk in chilly but calm conditions at about 08.30am, following the path up the gentle lower slopes of the mountain. Although the snow was hard at first, it soon grew deep and powdery. Time for snowshoes. At this altitude heather stalks and other terrain features poked up through the drifts, as if the slope had been drybrushed by a careful artist, but above we could see far more snow gleaming against a clear blue sky.

Chris took the lead and I watched his easy snowshoe gait as he followed the line of the path, sticking to the firmer snow where possible. Although we could have got by without snowshoes, it was certainly easier with them – and a lot more fun. But, after crossing the broad plateau at about 800m just north of the summit, things became steeper. A snow slope swept up ahead of us, broken by iced-over rocks, and after digging a small test pit I realised that the usual route to the right wasn’t in the best condition, with a weak layer beneath the surface indicating potential avalanche danger. Fortunately, the slope left of the ridge seemed a lot safer, but while I was changing snowshoes for crampons Chris told me that he wanted to head a different way. “Conditions might be slow over the summits,” he said, “and I’ve got to be back home this afternoon.”

It felt almost warm in the sun as I climbed steeply up to the crest of the ridge, crampons biting in that uniquely pleasing way crampons do when conditions are this good. Below me, I could see Chris getting smaller. He waved, and then I saw him making tracks down towards the other side of the plateau. Now I was on my own.

Bynack More’s summit, a calm and sunny perch above endless snows, was so different to the roaring maelstrom I’d experienced last time that it felt like a different place entirely. I tried to remember when I’d last seen winter conditions this perfect. Four years ago, maybe? Considered in the context of my entire lifespan, just how rare, how special, were these experiences – and did I always appreciate them as I should? I looked on to the cloud-wreathed basin of frozen Loch A’an, an abyss clenched between crags piled high with snow, and felt excitement rising within me at the journey yet to come. This, I thought, is living.

My journey alongside the shoreline of Loch A’an, blurred to invisibility by the deep snow banks above and the solid ice below, had been a slow one. I found myself enthralled by the intricate textures and swirls on the ice. The Shelter Stone Crag up ahead, a mountain bastion slashed by the diagonal rift of Castlegates Gully, called me on with its whisper of silence. And the silence in that cathedral-like space was absolute. When finally I paused beneath the mountain wall at the head of the loch, a sanctuary of deep cold and deeper shadow, the rustle of my jacket and the creak of my snowshoes dissipated with astonishing speed – as if quenched by a watchful spirit.

Colour flushed over the landscape as I climbed up to the plateau of Beinn Mheadhoin for the gloaming hour. I had my pick of sites for the tent; the snow was deep, firm and flat almost everywhere, and although I wasn’t expecting high winds I took my time to dig out really good T-slot anchors for my snow stakes. As expected, my body temperature plummeted as soon as I stopped moving. Even putting my down jacket on right away wasn’t enough to cut the chill, and it wasn’t until safely wrapped up in my sleeping bag with a pan full of snow melting on the stove that I started to feel warm again. Frost twinkled on the guylines. The moon was out, shining down between the stars, clear and bright and exquisite.

My night on the roof of the Cairngorms was everything I’d hoped it would be. I slept deep and warm, and woke before the dawn to see the Belt of Venus light up the sky above Coire Sputan Dearg in delicate gradients of rose and salmon and finally gold. The quality of light as I strolled up to the summit itself just after sunrise was like nothing I had seen before: colours of such richness and depth that the landscape itself seemed to glow. The entire Cairngorm plateau spread out in front of me, not a person or sign of civilisation to be seen anywhere, I felt emotions that defy all description and even now confound my attempt to cast into words.

With fine conditions and a clear sky, I could hardly be more excited about the journey ahead over the Cairngorm plateau. Although I briefly donned crampons for the steep descent directly to Loch Etchachan, for the rest of the day until almost back at the ski centre I kept my snowshoes on, and was glad of them.

I climbed past Loch Etchachan, buried and choked beneath an exceptional depth of snow, and made tracks up the ridge towards Ben Macdui in a rising wind and swirl of spindrift curling away from the crest. Suddenly the cold really began to bite and I struggled with my jacket as I added a layer on underneath. Ben Macdui’s summit was in the white room: a disorienting whiteout with no up or down until the wind tore a hole in the cloud and revealed a glimpse of some distant sunlit view. With an eye on my compass I navigated away from the summit, and soon started meeting other people again. A pair of young ski tourers said hello. A hillwalker wheezing at the effort of the soft snow said he wished he had my snowshoes. Back on the main track, which was easy to follow now despite the spindrift that had covered it in places, I soon dropped below the cloud base and romped down easy slopes beside Coire an Lochain, where I spotted a tent in a fine location behind a wall of snow someone had built to shield it from the wind.

Back at the ski centre and sipping a cup of coffee at the cafe, I took a moment to reflect and appreciate what I had done. “So glad conditions were good for you,” Chris texted to me. “Wish I’d been able to stay out. Hoping to get out again tomorrow. Glencoe Ski Centre is reporting four metres of snow!” Even though he lives in the area and has seen it all many times before, I always find his enthusiasm illuminating. It is easy to become jaded about these experiences, think about them purely as notches on the ice axe, but these are some of the best and purest moments of our lives. Simplicity, beauty, rarity, effort and reward combine to create something special. These moments offer an escape from the treadmill and a glimpse of something beyond all of us. Cherish them.

2025 coda

These days I seem to think a lot about the meaning or higher purpose of adventure. This, ladies and gentlemen, is it – or at least a good part of it. When we allow ourselves to be changed, moved, and surprised by nature (and our response to it) we become richer people. Sometimes it really is as simple as that.

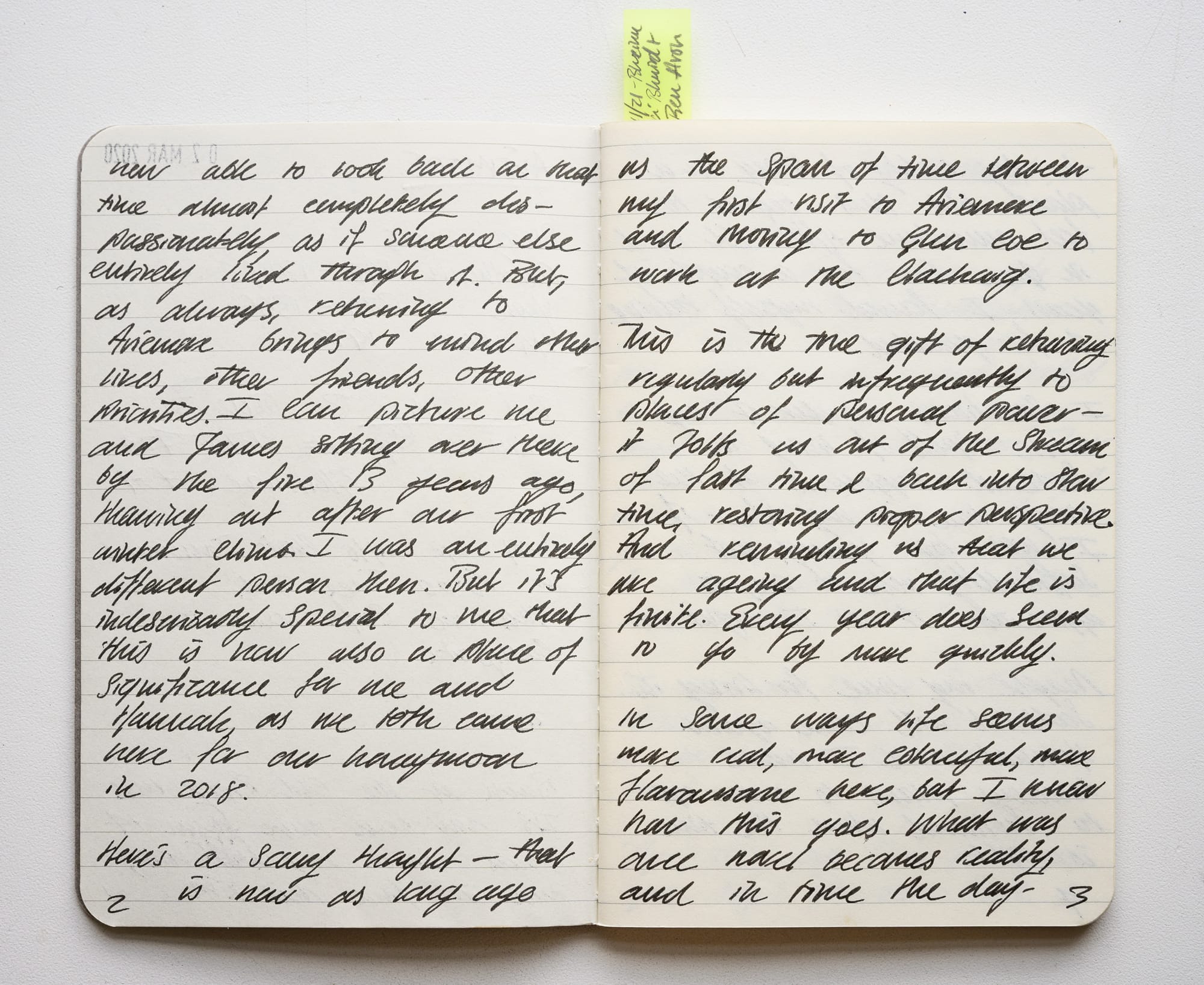

From FN5, written in Aviemore just before setting out:

Back in the Old Bridge Inn. It's now been more than 14 years since my first visit, and I find that I'm now able to look back on that time almost completely dispassionately, as if someone else entirely lived through it. But, as always, returning to Aviemore brings to mind other lives, other friends, other priorities. I can picture me and James sitting over there by the fire 13 years ago, thawing out after our first winter climb. I was an entirely different person then. But it's indescribably special to me that this is now also a place of significance for me and Hannah, as we both came here for our honeymoon in 2018.

Here's a scary thought – that is now as long ago as the span of time between my first visit to Aviemore and moving to Glen Coe to work at the Clachaig.

This is the true gift of returning regularly but infrequently to places of personal power – it jolts us out of the stream of fast time and back into slow time, restoring proper perspective. And reminding us that we are ageing and that life is finite. Every year does seem to go by more quickly.

In some ways life seems more real, more colourful, more flavoursome here, but I know how this goes. What was once novel becomes reality, and in time the day-to-day reality of living in a place like this begins to feel mundane. After I'd lived in Glen Coe for a couple of years I found myself taking it for granted.

I sometimes wonder if my own spell of living in Scotland happened at the wrong time in my life – if I was too young, not sufficiently able to see, to appreciate it as I ought to.

Maybe my time for living in Scotland will come again. Hannah and I have tenuous plans to move up to Scotland when the time is right.

Further reading: The Second Chance.

From JN3, written after returning home:

Does it really get any better? There has been much looking back recently at the 'winter of legends' ten years ago, but honestly, this was a vintage trip. The good old days aren't all behind us. Real winter still exists, and can still surprise us.

All images © Alex Roddie. Images produced using a camera and free of AI contamination. All Rights Reserved. Please don’t reproduce these images without permission.

Alex Roddie Newsletter

Subscribe here to receive my occasional personal newsletter in your inbox. (For the fun stuff, please consider subscribing to Alpenglow Journal instead!)